2021 Northwest Fish And Wildlife Year In Review

After putting together 2020’s edition of my annual Northwest fish and wildlife year in review last December, I was hoping the news firehose would simmer down in the new year.

No such luck as 2021 turned out to be quite active.

The conversation around what to do with Washington’s Snake River dams was one of the primary storylines of the year as an Idaho Congressman unveiled his comprehensive $33-plus-billion proposal to breach them, and so too was the crash of steelhead headed back to the Inland Northwest and Oregon’s famed North Umpqua.

The Columbia’s coho run didn’t come in like the bonkers preseason forecast suggested, but it certainly served up plenty of angling opportunities clear into the Wallowas and Wenatchee area.

New state record fish were caught, a backcountry hunter had a helluva experience as wolverines chased down his buck, poachers were popped with big penalties.

It was also another summer of big wildfires, a shockingly unprecedented heatwave, huge deer disease outbreaks and, in midfall, the incredibly depressing discovery of chronic wasting in four Idaho muleys and whitetails.

And the fish and wildlife commissions warranted extremely close watching as highly litigious parties also filed lawsuit after lawsuit – earning the ire of the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation in a sharp rebuke.

Ahhh, yes, it was quite a year, and while undoubtedly my news-dar missed a few items (hit me up at awalgamott@media-inc.com with suggestions to mull), below are stories I considered to be the most important in the year that just was.

JANUARY

It didn’t take long for 2021 to generate fishing and hunting news as literally on the very first day of the year I found myself blogging about changes to the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission, starting with Governor Inslee’s appointment of Fred Koontz who would be followed shortly by Lorna Smith, a pairing that quickly raised eyebrows for some members of the Evergreen State hook-and-bullet world. However, the governor stopped short on filling an Eastside seat, leaving the region underrepresented on the board that sets WDFW policies.

The events of a few days later also served notice that predator management would very much be part of the year’s conversation. On the same day I reported that Oregon and Washington officially took over full management of gray wolves as the federal delisting of the species everywhere in the Lower 48 became official – and which led to an immediate lawsuit from the usual suspects – two sisters followed through on their threat to sue over the latter state’s permit-only spring bear hunt. While their procedural claim was ultimately unsuccessful in court, it was also another sign the season had a target on its back.

Despite building pressure from anglers and the recently convened legislature, WDFW held firm on its boat-fishing ban on coastal steelhead rivers, a move meant to reduce the catch of native fish during what ultimately turned out to be the “lowest on record” return and saw nearly all rivers close by early March. Meanwhile, the ESA-listed Skagit-Sauk run rebounded enough to open for wild steelhead, albeit on a pared-back schedule from the previous season.

WDFW commissioners heard about a proposed, unique-to-the-Northwest wildlife area, a former coal mine on the Lewis-Thurston County line. Former operators TransAlta of Alberta wants to donate two-thirds of the 9,600-acre site it is working to restore and sell the agency the other third, and while there was support from some commissioners and the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, pushback from local governments and U.S. Rep Jaime Herrera Beutler saw WDFW pause their pursuit in spring. On the same front, later in the year, a 1,567-acre former alpaca ranch near Tenino was purchased by a private nonprofit with the intent of turning it over to WDFW for a future Violet Prairie Wildlife Area.

In another sign of increasing friction between predator advocates and the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission and WDFW, the approval of protocols for a legislatively mandated hound training program also saw fireworks as an out-of-state animals-rights extremist went out of her way to attack a commissioner for recent press statements. In light of events later in the year, it essentially was a “the lady doth protest too much” moment that suggested the board’s Kim Thorburn was onto something with her warnings in the Spokane Spokesman-Review that hunters were being seen by some “as an enemy.”

FEBRUARY

I’m not the sharpest reporter in the press pool by a long shot, but even I could see big news was imminent as elements of the Northwest salmon and steelhead world began focusing videos and online panels on the question of Lower Snake River dam removals to restore the runs and “keep everybody whole” just ahead of front-page Sunday articles in the Lewiston Tribune and The Seattle Times detailing Idaho’s US Representative Mike Simpson’s $33-plus-billion plan he hoped to hitch to the new administration’s infrastructure package. While the conservative Republican’s conversation starter was poo-pooed by a highly litigious environmental cadre that called the concept “disastrous” largely because it would bar them from suing over the river and salmon for multiple decades, it did eventually bring powerful regional Democrats to the table and by October the parties in a more constructive long-running hydropower operations lawsuit agreed to a one-year pause to work towards a “long-term solution” over the four dams on the lower Snake.

WDFW began two rounds of aerial captures of bighorns in an effort to stop the spread of pneumonia in the Yakima Canyon herd via a “’test and remove’ process that has been successful in other Western states” in controlling the often-fatal and long-running illness in wild sheep. Later in the year Movi popped up in a lamb in the otherwise disease-free Quilomene herd.

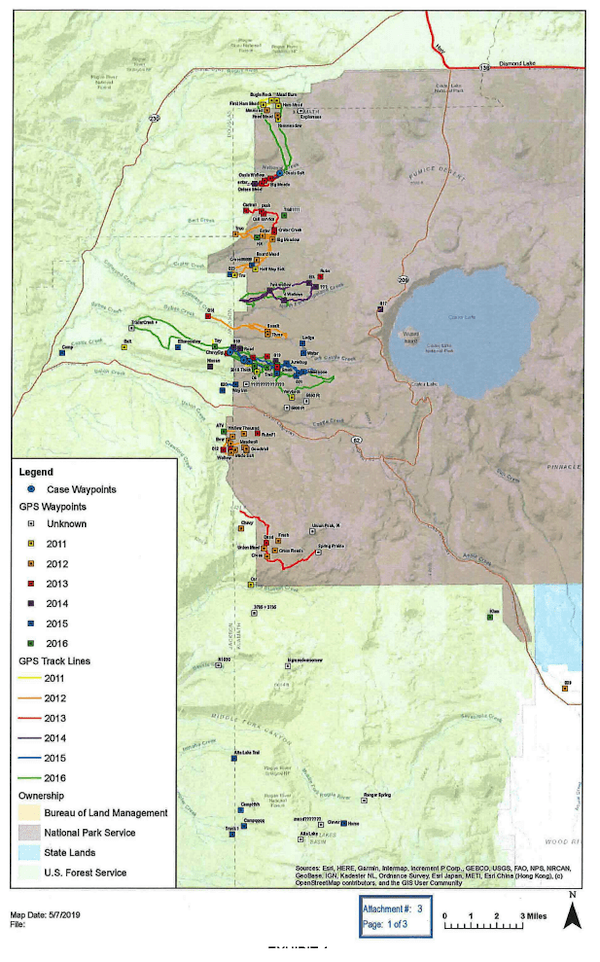

A Medford-area man who “used one of Oregon’s most valuable natural preserves as his private hunting ground” was banned from Crater Lake National Park, as well as ordered to pay $42,500 for killing five elk and a deer there in 2015 and 2016. Adrian Duane Wood, 44, of White City also lost his hunting privileges for five years while he is on federal probation, and was sentenced to a six-month stay in a halfway house. The US Fish and Wildlife Service detailed how teamwork and digital and DNA evidence brought Wood to justice.

WDFW chose the “full restoration” option for the Farmed Islands Unit of the Skagit Wildlife Area as it prepared to move forward with returning the legendary waterfowl hunting area to critical rearing habitat for ESA-listed Chinook and other stocks. The news came out the same day as $1 million in federal funding was awarded to the Department of Ecology and a local tribe to acquire more land on the nearby Stillaguamish Delta for restoration that will benefit fish and wildlife, part of $3.5 million disbursed for coastal resiliency work throughout Puget Sound.

You do good, American hunters and anglers, and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s 2021 disbursement of Pittman–Robertson, Dingell–Johnson Act and Wallop–Breaux funds, collected on sales of firearms, fishing gear and boat fuel, tallied $1 billion – $121 million more than the year before. The money went to all 50 “states to conserve, protect and enhance fish, wildlife, their habitats and the hunting, sport fishing and recreational boating opportunities they provide for generations to come.”

In what was dubbed the Wild Fish Conservancy’s “perhaps … most shameful lawsuit yet” before it was inevitably filed, the organization sued WDFW over its new integrated Skykomish broodstock summer-run hatchery program for alleged ESA violations, but after a judge stayed the lawsuit, NMFS signaled it didn’t have a biological concern with releasing the new strain into the river, 56,000 smolts were let go from Reiter Ponds and the feds ultimately approved the state and Tulalip Tribes’ hatchery genetic management plan covering the effort. It left WFC stewing – or maybe holding the bag? – and switching their lawsuitinator to full-auto as it strafed WDFW over a range of hatchery programs spread across Western Washington and several species.

MARCH

It was one-and-done for smelt last winter, but dippers still enjoyed a good day on the lower Cowlitz River, netting an estimated 91,000 pounds, or 9.2 pounds per angler. It was just the second opener since 2017’s. Stay tuned to our February issue for news on the 2022 return and what sort of opener prospects we might see.

The first Steller sea lion was lethally removed from Willamette Falls in early March, but most of 2021’s pinniped management activities occurred at Bonneville Dam, where 27 of the bigger marine mammals were taken out in spring and fall, along with 21 of the smaller California sea lions. (Eight CSLs were also removed at the falls.) The work is being done under a five-year federal permit and aims to reduce predation on ESA-listed salmon, steelhead and other stocks in the Columbia system. Increased funding from Washington’s legislature helped fuel some of this year’s efforts, but with the cost of the equipment needed to handle Stellers, a request has been sent to Congress to provide money to expand the work into tributaries. On a related note, ODFW developed a new online tool for anglers and the public to report seal and sea lion sightings.

With the pandemic continuing, last winter saw only two in-person Northwest sportsmen’s shows. Both were in Oregon and put on by O’Loughlin Trade Shows, which reported good business for some vendors and few safety compliance issues. The company benefitted by the state reclassifying trade shows as retail, but Washington officials “wouldn’t budge” off guidelines limiting “indoor entertainment” to a maximum of 200 people at a given time, forcing the cancellation of the big Puyallup as well as other organizers’ shows around the state.

Word emerged that five wolves had been found dead in close proximity to one another in Northeast Oregon in early February. Officials were very tight-lipped and initial details were sparse, but a retired federal wolf manager suspected poison. And indeed, late in the year it was announced that not only did the quintet die of poisoning, but so too had three other wolves in the same county later in 2021. In what’s believed to be the largest reward ever offered in an Oregon wildlife poaching case, $47,736 had been pledged as of mid-December for info that leads to an arrest or citation. Anyone with info is asked to call the Turn In Poachers, or TIP, hotline at (800) 452-7888, text *OSP or email TIP@state.or.us. The case number is #SP21-033033. Later in spring, ODFW reported the state’s wolf population grew 9.5 percent to a minimum of 173 animals, while WDFW said Washington’s jumped 25 percent to 178, and it’s probable 2021’s counts will again reflect annual increases in both states.

Two northern pike were caught in Lake Washington on the first day of a Muckleshoot Tribe warmwater test fishery, doubling the number of the nonnative predator fish known to have been illegally released in the lake (another was netted in 2017, while a bass angler released a fourth). While no more were subsequently caught, in an odd twist, over 100 American shad were reported caught as well, perhaps strays from the Columbia River. Or not.

There hasn’t been much news on the University of Washington’s and WDFW’s Predator-Prey Project, a legislatively mandated effort to figure out the impacts of wolves and cougars on deer, elk and moose – as well as each other – in portions of northern Eastern Washington, but a 13-minute video that debuted in late March provided an update of sorts on the five-year project that began in 2016. Results from all that prey and predator collaring in the Okanogan and Stevens and Pend Oreille Counties are expected to begin being published this coming year.

APRIL

Just after North of Falcon salmon harvest negotiations wrapped up, an Anacortes-based fishing organization filed a lawsuit against federal and state salmon overseers, in part claiming the agencies are violating ESA provisions related to the process for setting seasons. While portions of the suit were subsequently dismissed, a US District Court judge will hear arguments from Fish Northwest and responses from NMFS and WDFW in spring 2022.

There was potential good news for fans of fishing off the Emerald City’s Pier 86, closed for several years due to “public safety concerns.” The Port of Seattle, Expedia and WDFW funded a “Cost and Feasibility study … to determine the technical requirements and potential costs of construction of rebuilding the public fishing pier … with a ‘ferry float.'” Later in the year, DNR and a boating foundation purchased a historic Deep South Sound marina they aim to spruce up and improve nearby salmon habitat.

A jarring story in the Lewiston Tribune sounded urgent alarms about the Snake River’s wild spring/summer Chinook and steelhead, reporting that 42 percent of the former stocks and nearly 20 percent of the latter “have reached the quasi-extinction threshold.” It was based on a Nez Perce Tribe study of 31 of 32 spring/summer Chinook stocks and 16 steelhead stocks and “demonstrates you better do something or you are going to lose your ability to do much of anything,” David Johnson, tribal director Department of Fisheries Resources Management, told reporter Eric Barker, who pounded the Snake dam beat like a champion drummer this year. The Nez Perce are among the groups, which include the state of Oregon and Northwest Sportfishing Industry Association, pushing to remove the concrete plugs.

Washington’s commission approved a new Anadromous Salmon and Steelhead Hatchery Policy, which members called a “significant update and improvement to the previous policy” it supersedes, while also stressing “wild fish are going to be taken care of.” It more closely aligns state and tribal production efforts and brings reviews back “in-house” instead of sent out to the Hatchery Scientific Review Group. It was targeted in a subsequent Wild Fish Conservancy lawsuit.

The end of the 2021 state legislature left WDFW “well positioned for the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead,” thanks to strong funding from lawmakers and no need in the end to slash 15 percent from the agency budget, as feared in mid-2020 with the rise of Covid and which would have equated to $31 million and wiped out the $27 million from the General Fund that WDFW had secured the year before in lieu of fishing and hunting license increases.

MAY

WDFW began capturing 125 elk calves in the Blue Mountains in an effort to figure out why so many are dying and the herd there has shrunk to its lowest levels in 30 years, despite sharply reduced antlerless tags. It was a two-pronged effort that includes an assessment of the “literature” – the copious research that’s been done on elk in Washington’s as well as Oregon’s Blues – as a step towards possible predator control.

After half a year without any clam digs on the Washington Coast, marine toxin levels dropped back into the safe zone and state managers were able to reopen Mocrocks beach for two days of digging, then added four more. Meanwhile, Oregon officials had to put out a press release warning that fish and wildlife troopers and local police would be citing anyone partaking in “unauthorized razor clamming” on North Coast beaches, which were still closed at the time due to high domoic acid readings.

The first of two new-in-2021 Oregon Fish and Wildlife Commission members were named by Governor Kate Brown and confirmed by the state Senate. Dr. Kathayoon Khalil of Portland joined in mid-May, while Dr. Leslie King, also of Portland, came on board in November. The Oregon Hunters Association expressed cautious optimism with both appointees, telling me that they interviewed King while she was at a duck club between hunts.

ODFW also upped its attack on Coquille smallmouth, again OKing the use of spears, spear guns and bait for the illegally introduced bass that the agency says is keeping the river’s fall Chinook from rebounding like other coastal stocks, and raising concerns about lamprey predation as well. Along with the expanded angling options, ODFW also put together maps of river access points and bronzeback distribution, as well as created a video on how to spearfish in the Coquille and fillet up your catch.

JUNE

In what feels like a more and more common and pressing problem in the usually moist, generally temperate Northwest, a dry end to spring and large swaths of the region in deep drought conditions had fish managers worrying about what it might mean for summer flows and angling conditions. Indeed, by the end of the month – during the hellwave that sent temperatures soaring to all-time records of 116 in Portland, 110 in Forks and 108 in Seattle, and pushed water temperatures in the lower Yakima River to nearly 89 degrees – ODFW announced hoot-owl or other restrictions for salmon, steelhead, trout and sturgeon angling on several streams. Meanwhile, USFWS hatchery crews scrambled to move and release millions of young spring and fall Chinook before the heatstorm hit. And following reports of massive dieoffs on the tideflats exposed to oven-level temps and low tides, in early July WDFW set up a website where the public could report concentrations of dead fish and shellfish. While we might have escaped 2015’s huge loss of sockeye salmon in the Columbia, in September 2,500-plus spring Chinook succumbed in the South Fork Nooksack due to a bacteria enhanced by too-warm waters and exacerbated by habitat loss and climate change, per the Lummi Nation. Scouring fall floods only added to salmon woes in this part of Northwest Washington.

Meanwhile, an outbreak of viral adenovirus hemorrhagic disease, or AHD, hit blacktail deer in the San Juan Islands hard, with one subscriber with land on Orcas Island reporting “dead deer all over.” It was followed later in summer by even more widespread and larger dieoffs of whitetails from another hemorrhagic disease, EHD, across the eastern tier of Washington and Clearwater Basin of Idaho, reducing fall hunter harvest. Mule deer and bighorns were also impacted by the disease spread by gnats as water sources dried up.

An Oregon initiative to dramatically expand animal cruelty laws and which would effectively ban fishing, hunting and trapping had Beaver State hunting, farming and other interests redoubling warnings about the consequences if enough people sign a petition to bring it up for a public vote this fall. “While we may think that it is impossible for such a far-fetched idea to make it to the 2022 ballot, let alone get passed, we must take this threat seriously,” the Oregon Hunters Association said on a special webpage it set up to track the petition.

Even as federal and state dollars helped boost salmon production in Washington by some 11.6 million smolts in an effort to provide more prey for starving southern resident orca whales as habitat restoration work for wild Chinook ripens over the coming decades, the Wild Fish Conservancy requested a US District Court judge halt NMFS’ funding of the program as part of a broader lawsuit against salmon fisheries in Southeast Alaska, and they went to a Thurston County Superior Court judge to block the state’s Orca Prey Initiative, a host of WDFW salmon hatchery expansion plans and a new Fish and Wildlife Commission policy until they undergo State Environmental Policy Act or environmental impact statement reviews.

JULY

A hot start and a small Chinook quota led to an early and abrupt closure in the San Juans. It meant islands anglers will only see seven days of salmon fishing during the entire 2021-22 season, down from as much as seven months (in the pamphlet) as recently as half a decade ago, and further fueling anger over North of Falcon season setting that has routinely trimmed opportunity for Puget Sound blackmouth and other kings in recent years.

Underlining the critically dry and dangerous fire conditions across much of the Northwest, an entire national forest spanning two states was shut down to public entry as blazes erupted in the Blue Mountains, leading to state wildlife area and DNR land closures as well. While the 2021 fire season wasn’t as bad as 2020’s, some 800,000-plus acres still burned in Oregon – half by the Bootleg Fire southwest of Summer Lake – and 650,000-plus acres were scorched in Washington, affecting hunter access during some late summer and fall seasons.

In a first for Washington, biologists captured and collared a female grizzly bear near Metaline Falls, near where the state and Idaho and BC come together. The animal, which had three cubs in tow, was roaming what’s known as the Selkirk Recovery Zone, where lone males have been caught in the past. Meanwhile, reintroducing the other rare critter that once trod these same highlands – mountain caribou – seems to be a longer and longer shot as Canadian officials focus first on saving their own struggling herds.

In an order that turned heads for its sharpness, a federal judge told the Army Corps of Engineers to “make immediate and extensive changes to the way it operates the 13 dams in the Willamette Valley, including Detroit Dam, to give native species of fish a chance to survive,” per the Salem Statesman-Journal.

A “last-ditch effort” and “emergency action” to restore the Lake Washington sockeye run to fishable size saw WDFW, Seattle Public Utilities and the Muckleshoot Tribe catch 279 of the salmon at the Ballard Locks and take them directly to four special spring-fed tubs at a hatchery on the Cedar River. It was a test to see if bypassing the lake’s too-warm, disease-rich waters would increase adult survival, and wouldn’t you know it, it did. All but two of the fish lived into October, a “phenomenal success,” and were expected to yield 441,600 eggs. While some people are ready to throw in the towel on the urban salmon run, the experiment provided a glimmer of a glimmer of hope to fans of the famed urban fishery.

First it was pandemic-related printing material shortages and then wildfires led to a very long delay in the arrival of WDFW’s 2021-22 fishing pamphlet at license vendors and other outlets across Washington. While the regs took effect July 1 – and were available in several online formats – the printed version of the rules, which many anglers prefer, didn’t show up until very late in the month.

In what initially seemed like a case of very fishy timing and definitely served as another blow to angler access, the Dash Point Pier in Tacoma closed just as Chinook, coho and pinks began to arrive in local waters. The overwater structure allows fishermen to huck their Buzz Bombs, etc., even further out into the salt, but the city parks department said it was closed following local residents’ structural concerns, a “preliminary assessment, and out of an abundance of caution and concern for the public’s safety … until they are able to complete a full evaluation and prepare a report with recommendations for repair and/or renovation.” Even as some wondered about the locals’ real reasons, as of the end of the year, the pier was still off limits.

Still, the hits kept coming for Puget Sound anglers as the Army Corps of Engineers denied WDFW a permit to build a small new one-lane concrete boat ramp at the site of an old fishing resort at Point No Point. It left Director Kelly Susewind “deeply disappointed” after his agency had spent several million dollars acquiring the site, drumming up plans and removing old creosote pilings. The Corps’ Seattle District engineer Col. Alexander “Xander” Bullock said the concrete strip sans docks “would result in an impermissible abrogation of the Suquamish Tribe’s reserved treaty rights because of the extent it would impair or obstruct the Tribe’s access to its usual and accustomed fishing areas,” which was welcome news to the tribe’s chairman, Leonard Forsman, but ramp proponents warned the logic could be applied Puget Sound-wide by the federal agency in charge of permitting in-water work.

AUGUST

ODFW launched a new integrated spring Chinook broodstock program on the Clackamas meant to revitalize a failing out-of-basin strain and improve fishing on the river and downstream in the Willamette. Federally approved plans call for biologists to collect 120 wild fish annually from throughout the run starting this past year and for the next two, releasing 1.2 million smolts in three locations on the system, and keeping the natural-origin run’s genetics as close to natural as possible by mixing in eggs and milt from 21 to 45 native females and males, depending on run size, in subsequent years.

In an alarming development for one of Oregon’s strongest stocks but also a harbinger of bad news for summer steelhead up and down the West Coast, most of the North Umpqua and all of its tribs were closed to fishing as early counts at a dam near Roseburg were just 20 percent of average – slumping to a mere 10 percent by mid-September and the run’s 90-percent-complete date.

On the Columbia, the words “terrible,” “meager,” “darkest hour” and “worst on record” were used to describe the A-run of summer steelhead when the forecast was reduced from an already low 89,000 to just 35,000. Even as fishery managers had put rolling protective measures in place, one guide cancelled his season on the Deschutes, a cold-water refuge, and further restrictions were subsequently instated, including banning boat fishing and then all bank fishing on upper Drano Lake, and a number of Oregon and Washington waters. While the run ultimately came in stronger than that dire inseason downgrade, if I’m not mistaken the combined year-end tally of 69,076 A- and B-runs was still the lowest on record back to 1938’s creation of Bonneville Dam, and restrictions will continue into 2022 in all three Northwest steelhead states.

Lorraine Loomis, chair of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission and longtime Swinomish fisheries manager, died August 10. She was 81 and had been the chair of the multi-tribe commission since Billy Frank Jr. passed away in 2014. It was termed “another tremendous loss” by the Stillaguamish’s Shawn Yanity and her life was remembered as one of “profound impact across the region and within her tribe,” said WDFW’s Susewind.

A stunning landscape in Oregon’s Blue Mountains moved into ODFW ownership as the Fish and Wildlife Commission signed off on the phase-one purchase of almost 5,000 acres along the Minam River between La Grande and Enterprise from Hancock Natural Resource Group with funding from the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation and the federal Wildlife Restoration Program. Another 11,000 acres are on the docket and it will all be added to the Minam River Wildlife Area, providing a permanent mix of hunting, fishing and recreational access and securing habitat for elk, deer and so many other critters.

And in late August WDFW announced an incredible 62 days of razor clams digs coming up on the coast through the end of 2021, and what’s more a bonus limit would be in effect, allowing diggers to harvest 20 a day, up from 15, thanks to high clam abundance. ODFW also later reported a “very promising season” ahead for its North Coast beaches. While the 2020-21 season had looked just as bright from the same vantage point a year before, this time domoic acid closures stayed away and shellfishers from both states were able to enjoy a great fall, with still more opportunity coming up well into the New Year.

SEPTEMBER

Though the Columbia’s silver run didn’t quite live up to its glittering preseason predictions, a buttload of fish still returned, allowing for boosted limits on the Lewis and other Southwest Washington rivers, a Lower Columbia reopener, openers on the big river from Priest Rapids Dam up to Wells Dam and on lower Icicle Creek, and a second straight season on Oregon’s Grande Ronde. That last one is in part thanks to Nez Perce reintroductions (ODFW is also involved), and similar tribal restoration helped power a whopping 64,336 coho counted at the Upper Columbia’s Rock Island Dam, eclipsing the old high mark by 20,000. Well downstream in the system, the 10,000 wild coho counted by Portland General Electric at North Fork Dam on the Clackamas was also record and credited in part to the utility’s fish-passage work.

Speaking of fish passage, WDFW, the Yakama Nation, Cowlitz Indian Tribe and American Rivers praised NMFS’s and USFWS’s U-turn on a Trump Administration preliminary decision that would have meant PacifiCorp could have mitigated its three North Fork Lewis dams with just habitat work alone. While there already is an adult fish collection facility and a downstream floating surface collector at either end of the hydropower system, four more fish passage structures are called for in 2004’s federal relicensing agreement.

For the first time since 1972, Washington’s grouse season started on a date other than September 1 as the Fish and Wildlife Commission pushed the opener to midmonth, a move meant to protect mother ruffies and blues and their broods, which make up a strong portion of the early harvest, affecting survival of young-of-the-year birds and in turn leading to a longterm population decline. While undoubtedly decreasing harvest – Labor Day weekend was a favored time to get into the woods to find coveys – hunting was also extended into mid-January.

The end of summer was also a hopping time on the wolf front. While the Biden Administration has so far sided with the Trump Administration in upholding the delisting, federal wildlife managers announced they were beginning a “comprehensive status review of the gray wolf” in Washington, Oregon and elsewhere in the West following their initial analysis of a pair of petitions that asked for the predators to be relisted under the Endangered Species Act. The move was driven in part by Idaho and Montana legislatures’ passage of laws allowing a range of tactics to be used on wolves, up to and including use of night vision equipment and essentially bounty payments.

To preserve forage for southern resident killer whales, NMFS adopted restrictions for years of low Chinook abundance off Washington and Oregon’s North Coast. When fewer than 966,000 of the favored salmon are expected to be present, Amendment 21 will kick in, largely impacting the nontribal commercial fleet but also recreational anglers in certain times and places. The numerical figure represents the average preseason forecast of the seven poorest years of Chinook abundance in the ocean off the tip of the Lower 48. It’s been more than a decade since the last time it would have been tripped.

Researchers at Washington State University discovered at least one way elk are catching the crippling hoof disease now found in all but two of the state’s herds: “exposure to soil contaminated with hooves from affected elk.” As work funded by the state legislature continues, WDFW also hopes to reduce the disease’s prevalence through an incentive program in which hunters who kill an elk with it could win some pretty sweet permits to pursue Western Washington bulls.

News that a Salem man allegedly tried to make off with 135 Yaquina Bay Dungeness caught off the public pier near the Rogue brewhouse – including 95 illegal-to-keep females, as well as a number of too-short males – put a sharp spotlight on the issue of shellfish overlimits striking Northwest beaches the past two years, and had me calling on local prosecutors to make an example of Dave R. Langimeo, 35, just like they did earlier in the year with the Hermiston couple who were sentenced for illegally selling recreationally caught crabs.

Way up in the heights of the Olympics, year four of five of mountain goat removals concluded with 113 animals culled in aerial operations carried out in the national park, bringing to 525 the number of billies, nannies and kids that have been translocated to the Cascades or shot by ground-based or helicopter crews since September 2018. 2022 will be “the last year” of “active management” efforts that aim to sharply reduce the number of goats brought to the peninsula in the 1920s for hunting.

Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission members rolled out a draft of a new conservation policy for the panel and WDFW, a document that offered an updated definition of conservation based on a “modern synthesis of the term” for a changing world, but one that drew immediate pushback for its language, “very us vs. them feel” and more. It made its debut as litigious environmental groups, conveniently trying to build on a recently released workplace audit of WDFW, urged Governor Inslee to name more “reform-minded” commissioners in the vein of Koontz and Smith. This hook-and-bullet-and-habitat writer’s tinfoil hat might be on a little too tight at times, but it all amounted to another signal that there’s a lot to be paying attention these days.

A major piece in RMEF’s September-October Bugle magazine said what some have suspected for years: Are the environmental groups suing the feds willy-nilly through Equal Access to Justice Act provisions really just in it for the money? “The really unfortunate thing is when these groups win, the Department of Justice negotiates the fees, but it’s the individual agency that must pay. So, in this case, it would impact the budgets of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, but in other cases it could be the Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management or another federal agency,” said Blake Henning, RMEF chief conservation officer. “All of those agencies are already underfunded, and this just hurts them more, which means they don’t have staff to adequately review issues, which leads to more and more lawsuits. It’s become what amounts to a ridiculous, non-stop merry-go-round ride.”

OCTOBER

Not only did a pink salmon inexplicably show up at Lower Granite Dam on the Snake, but a handful swam up the Wenatchee River, leading to “a lot of head scratching” about what the odd-year fish might be up to. Humpies have more of a “propensity” for straying than their cousins in the North Pacific and perhaps it’s just a function of a few of 2021’s large run to Pugetropolis streams getting lost, but a researcher at USFWS’s Leavenworth Fisheries Complex who looked into tribal fisheries in the area reported that the species at one point migrated upstream as far as Icicle Creek. In other weird wildlife wanderings, a gray whale was spotted in the Columbia off Sauvie Island during the springer fishery.

As Governor Inslee’s vaccine mandate deadline arrived for state workers, 38 WDFW staffers were initially reported “separated from service,” as the saying goes, a number that grew to 56 by early December, including 42 listed as initiated by the agency, and seven employee-initiated resignations and seven early retirements.

Oregon Coast Range poacher William Huet Hollings IV, aka Willy Hollings, was the subject of a big article in the Willamette Week after being sentenced to a year in jail, fined $40,000 and told he could never hunt again.

Despite an early start in the Tri-Cities and an extended season there and elsewhere, it was a down year for the Pikeminnow Sport-reward Program, with the 89,537 qualifying fish turned in the fewest on record and the effort of 11,543 also the lowest. However, there was the silver lining as the goal of catching 10 to 20 percent of the population of salmon-smolt-snarfing predators in the Lower and Mid-Columbia and lower Snake Rivers was once again reached, “as it has for every year since 1998,” per manager Eric Winther.

A Washington bowhunter had an out-of-this-world backcountry experience. As he waited for a buck he’d arrowed to expire, a family of three wolverines came along, chased it over a cliff, gnawed on its velvet antlers and otherwise raised hell in a remote valley in the Glacier Peak Wilderness. “It was unbelievable, but it happened,” said Travis Van Noy.

With chronic wasting disease, an always-fatal deer family malady, knocking on the door of the Northwest, riflemen saw more game check stations in Northeast Washington than usual during the general and late deer seasons as WDFW and volunteers teamed up in a new program to test whitetails. CWD isn’t in the state yet, but in a chilling development, it was confirmed in two mule deer bucks harvested in Idaho’s Unit 14 between Grangeville and Riggins in October, the first known infected animals in the tristate region. That led IDFG to create a CWD surveillance zone and issue 1,527 tags for a special emergency hunt in the area in December to gather some 775 samples for testing to see how widespread the outbreak might be. It’s not clear how CWD leapfrogged so far, as the next closest occurrences are well to the north and east, near Libby and Dillon, Montana, respectively. The news also had ODFW intensifying monitoring in Northeast Oregon, just across Hells Canyon from the region of the Idaho outbreak – which in late-breaking news is now up to four deer, with results from 72 more animals still pending – and next year will see mandatory check station stops for hunters transporting big game and in all likelihood WDFW will move to monitor Southeast Washington ungulates. Meanwhile, well to the east, the US House of Representatives passed a bipartisan bill that would help fund the fight against CWD. Here’s hoping the Senate takes up a similar measure in the New Year.

NOVEMBER

A new report cracked the door a little wider on Columbia shad, a species with a future as “bright” as their scales, but with so much still unknown about the East Coast imports and their potential impact on native salmon and steelhead, the Independent Scientific Advisory Board also recommended a “systematic, multiyear research program” because “potential risks for the ecosystem and anadromous salmonids warrant caution and continued attention.” Shad now comprise as much as 90 percent of all upstream-migrating fish in the big river some years, with recent runs the largest on record. And with a growth rate that averages “4.7 percent per year,” there’s “no indication that the population has reached an abundance limit.”

In a brazen series of thefts, a man and woman from western Skagit County allegedly stole 10 rifles and shotguns, plus ammo, chainsaws and other hunting and camping gear from elk camps set up near Rimrock Lake in western Yakima County – including after hunters had helped them change a flat tire their car got in the woods. The primary suspect, identified in county police and prosecutor records as Travis Robert Shipman, 37, of La Conner, allegedly told deputies he was short on money and knew it was hunting season, so his plan was to steal as many rifles and other things from hunters as he could to resell them. Last month he pled not guilty to charges of unlawful possession of a firearm in the first degree and possession of a stolen firearm. A court hearing yesterday in Yakima saw new dates set for further proceedings.

The disappearance of elk hunter and Seattle Fire Department deputy chief Jay Schreckengost near Cliffdell northwest of Yakima sparked a massive search-and-rescue effort involving “60 different agencies and organizations and thousands of hours from professional and trained volunteer searchers,” per the Kittitas County Sheriff’s Office. Schreckengost’s body was found 12 days after he told relatives he was going out scouting and just a half mile from where his vehicle was parked; it was reported he’d fallen “down steep hillside or cliff faces more than once before coming to rest where he was found.” Fire vehicles and personnel parked on overpasses to salute the vehicle carrying his body home to Stanwood.

Drew Monsey, an Oregon hunter with cerebral palsy, bagged a very nice Northeast Oregon elk after several days of searching for a big bull, a great achievement for an all-around Northwest sportsman limited to a wheelchair, in this case a tracked one that allowed him to navigate through the woods with his support team. Way to go, Drew!

ODFW put out word that starting in 2022, nonprofit groups that host veterans and active-duty military members on fishing or hunting trips “will be able to receive free fishing and shellfish permits for participants in their excursions” as part of a state effort to get them into the outdoors.

Clear winners in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, passed by Congress and signed by President Biden in November, were salmon, deer and other species trying to get around migratory barriers. The bill provides $350 million over the coming five years “for state, local, and tribal governments to construct wildlife crossings that reduce human and animal fatalities and injuries caused by the more than 1 million wildlife-vehicle collisions that occur each year.” That’s great news after Washington lawmakers early in the year sped away from an $18 million proposal to build six critter underpasses and 11 miles of deer fencing along a deadly stretch of U.S. 97 in Okanogan County.

In a staggering but also not entirely unexpected deadlock, Washington’s Fish and Wildlife Commission tied on the 2022 spring black bear limited-entry hunt proposal, putting it on pause for a year, a victory for hunt opponents who had mounted a successful public pressure campaign against it following a loss in court earlier in the year. Biologists and state managers did not have any real conservation concerns about the black bear population, and the decision drew increasingly stronger pushback from hunters, one of whom felt “disgusted, blindsided and frustrated with the vote,” which turned on Chair Larry Carpenter’s thumbs down, couched as a chance for WDFW to “confirm the accuracy of our information and cover our bases in the assault on this hunt.”

Following a massive population explosion, more than 70,000 invasive European green crabs were reported removed from a North Sound shellfish and salmon rearing facility. The Lummi Nation’s Lummi Sea Pond was described as a “perfect breeding ground” for the unwanted crustaceans which are feared for their potential impact on salmon habitat and native crabs.

DECEMBER

In a break from last winter’s blanket coastal steelhead rules and how they were rolled out relatively quickly, after lengthy public involvement WDFW Director Kelly Susewind OKed boat fishing on sections of three Forks-area rivers and kept last year’s regs on Willapa Bay rivers, but shut down angling on state-managed sections of Grays Harbor, upper Quinault, and Queets/Clearwater rivers due to chronic below-escapement-goal returns to them and likely continued run struggles. While protective of wild fish important to treaty and nontreaty fishermen alike, it also means thousands of harvestable hatchery steelhead will go uncaught on tribs like the Humptulips, Wynoochee and Skookumchuck, though Olympic National Park kept a sliver of the Queets’ Salmon open through December for clipped fish.

Firmer details began to emerge on WDFW’s Blue Mountains elk calf study, and they were grim, as managers reported an “exceptionally low” survival rate, just 11 percent, through the young wapitis’ first 150 days, with predators known to have killed at least 77 of the 125 collared animals and 54 of their deaths attributed to cougars. It had Game Division manager Anis Aoude telling the Fish and Wildlife Commission, “I think we need to do something. Otherwise, there may be very few elk left, given the trajectory that we’re seeing,” and at least one member agreeing the herd was in “crisis.” But in a jaw-dropping series of comments, two other members, 2021 appointees Koontz and Smith, essentially argued, what crisis, let’s just lower the goalposts on the herd population objective and consider reducing hunting opportunities even further instead. Between that and their no vote on spring bear, they really stepped in it, and hunters and a tribal wildlife manager let them know that the next day during public comment before the full commission. Seattle radio broadcasters Tom Nelson and Dori Monson also brought it to the attention of their listeners.

On the flip side of the predator-management-averse spectrum, USFWS reported that with Hart Mountain bighorns having declined a stunning 67 percent in just four years due to “high cougar predation” and habitat issues linked to juniper and weed invasion, it will “temporarily and strategically” kill big cats in sheep habitat to help the herd recover to more sustainable levels while addressing landscape issues over the long term.

Back on the Washington spring bear hunt front, WDFW’s Susewind expressed confidence during an online regional open house that the permit season would only face a one-year pause and said that he and his staff would be “working our butts off” to keep it that way. “We think it’s a good opportunity. We think the population can sustain it, so we’ll be continuing to work towards a [2023] season next year,” he told those who tuned in.

A few days later, Fred Koontz announced that he was resigning from the Fish and Wildlife Commission before the first full year of his six-year term was even up. He cited a “politicized quagmire”; in comments presaging the move, he also acknowledged having “been in the commissioner doghouse more often than I’ve been out.” It’s one thing to offer new ideas and takes, that’s fine; it’s another to try to rewrite WDFW’s conservation policy, vote to pause a long-standing hunt, disregard the local biologist’s professional opinion that an elk herd’s size is in fact “appropriate” and not expect to experience some vociferous opposition. Kitchen, meet heat. The departure had pro-hunting and preservationist-oriented groups urging Inslee to fill two empty Fish and Wildlife Commission seats – one of which represents the Eastside and has been vacant for an entire year now – with friendly-to-their interests members.

The Colville Tribes’ Fish and Wildlife Department reported Chinook spawned above Chief Joseph and Grand Coulee Dams for the second straight year, with over six dozen redds counted in the Sanpoil River this fall. To the east, 51 summer kings were released into the Spokane River, all part of an effort to build support for restoring salmon above the two fish passageless dams.

After a couple years of debate and a “marathon public comment session,” Oregon’s Fish and Wildlife Commission maintained the state’s conservative bag limit on wild steelhead on select South Coast rivers as part of the overarching Rogue-South Coast Multi-Species Conservation and Management Plan. Those in favor of switching to catch-and-release – like everywhere else in the Northwest – focused on climate change, conservation and data uncertainties, while those in favor of continued limited harvest pointed to ODFW staffers’ judgment that doing so wouldn’t harm the population.

Governor Inslee outlined $187 million worth of “ambitious legislative and policy proposals” that would focus on the protection and restoration of salmon habitat, fix fish passage barriers, address predation and “align harvest, hatcheries and hydropower with salmon recovery,” among other actions, ahead of the 2022 legislative session. The primary element, dubbed the Lorraine Loomis Act, after the longtime Swinomish and tribal fisheries leader who passed away earlier this year, would invest $123 million protecting riparian areas “from development, incorporate the standard in local land use plans, and provide landowners with financial assistance to help them meet the new requirement.”

Even as lawmakers boosted their budget in the 2021 legislature, WDFW game wardens, fish and fisheries benefitted from the donations of tens of thousands of dollars worth of rafts, waders and boots, 40 remote cameras and even a drone to help patrol Westside streams, as well as the Spokane River. “We appreciate their generous donations of equipment which will allow our officers to monitor secluded areas with the use of cameras and to access these remote areas with rafts and personal wading gear,” said Capt. Dan Chadwick of the equipment gifted by the Wild Steelhead Coalition, Wild Steelheaders United, Wild Salmon Center, Simms, Outcast Boats, and Sawyer Paddles & Oars.

Many salmon and steelhead runs and fisheries suffered this year, but there’s hope for the future as ODFW reported that a NMFS survey of the Pacific off the Northwest coast in 2021 found conditions “were the second-best since sampling of ecosystem indicators started in 1998. These improved conditions should result in better ocean survival and subsequent adult returns.” Cross your fingers! Meanwhile, the total 2022 Columbia springer run is forecast to come in at 197,000, well up from this year’s actual return of 153,000.

There’s dedication and then there’s battling arctic conditions, a power outage and the loss of not one but two water pumps to make sure that some 1.5 million spring Chinook, 1.85 million coho, 100,000 early winter steelhead and a “bunch of trout” survived what could have been a series of Christmas night disasters at WDFW’s Kendall Creek Hatchery. Kudos to the staffers who saved all those fish!

And let’s keep the good news rolling as we wrap this 8,500-plus-word spiel up with the story of how on Christmas Eve, two Northeast Washington coyote hunters ended up helping save a half-dozen elk that had broken through the ice of the frigid Kettle River. Jeff Stuart and Jordan Fish rallied family members and others, and using “ropes, kayaks, sleds, a winch and whatever else they could get their hands on,” they hauled six cows and six calves out of the water. Thanks to their heroic efforts – “We laid with these elk, We did CPR on these elk. We cried over these elk. We were strong for these elk as a group,” wrote Stuart’s wife Rylee on Facebook – half of the rescued animals survived, and the meat from the elk that died was allowed to be salvaged. “I would do it again in a heartbeat,” Rylee told a Spokane TV station.

And in a heartbeat or two, we’ll start a whole ‘nother year. See you then!

CORRECTION, 9:37 A.M., JANUARY 8, 2022: The first listing and image in the December section incorrectly reported that the Willapa Bay system was closed for steelheading this winter. In fact, the Bear, Naselle, Nemah, Palix and Willapa Rivers, along with Smith Creek, are open through either March 1 or April 1, depending on the stream. See this WDFW emergency rule change notice for specifics.