More On Elk Calf Woes In Washington’s Blue Mountains, WDFW’s Investigations

The news I posted Wednesday that WDFW will attempt to capture and radio-collar 125 Southeast Washington elk calves this spring to determine the reasons why so many are dying before they even reach a year old drew a pretty strong well-duh pushback on Facebook: Lions and wolves and bears, smart guy.

So why the hell even bother with this study?

“Because it’s never that straightforward,” Anis Aoude, agency Game Division manager, told me. “Having done ungulate management now for two decades, it’s never just predation.”

Aoude pointed out that the same exact predator guild exists in Northeast Washington, “but those elk populations are not having a problem with calf recruitment,” according to recent Predator-Prey Project work there he cited.

Both regions are strongholds for the state’s packs. They’re thick with cougars and bruins too, and all three species (plus some other toothsome ones) take their toll on elk calves, as they have evolved to over the eons.

But there’s another element to consider.

“Nutrition is a huge factor. That’s what we need to ferret out,” Aoude said.

And ferret out fast whether it’s the quality of forage available across the seasonal ranges of Blue Mountains elk, predation or a combination of the two that has led wapiti numbers this year to dip to – at a minimum – a 30-year low.

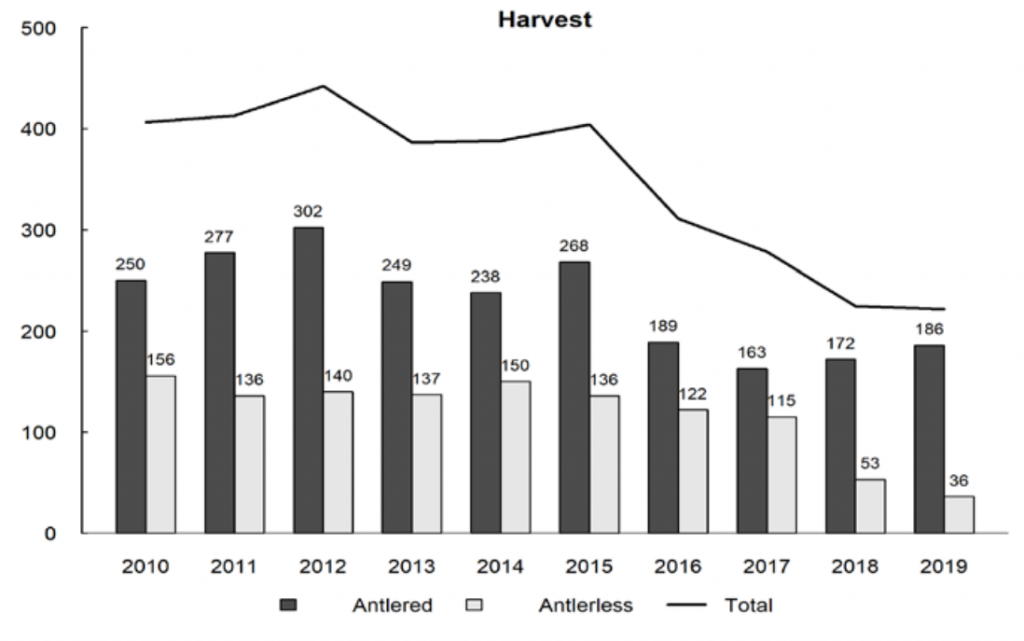

Hunter harvest has also sagged. Last year’s kill was just half of what it was a mere six seasons ago.

That’s partially a function of reduced antlerless permit opportunities starting in 2017 that otherwise should have spurred a herd rebound by now but hasn’t, but also strongly influenced by how many bulls are surviving their first year to grow a set of spikes and become legal for general season hunters.

Figuring out what’s going on and addressing it is critical, as WDFW says the herd “plays an important role in this region’s ecosystems and provides the public with hunting and wildlife viewing opportunities.”

“We want folks to know we’re working on it,” said Aoude of his agency’s press release announcing the “elk calf monitoring project” set to begin imminently between Dayton and Asotin Creek. “We do pay attention to this population and where they’ve declined and not rebuilding, we want to take a look at them.”

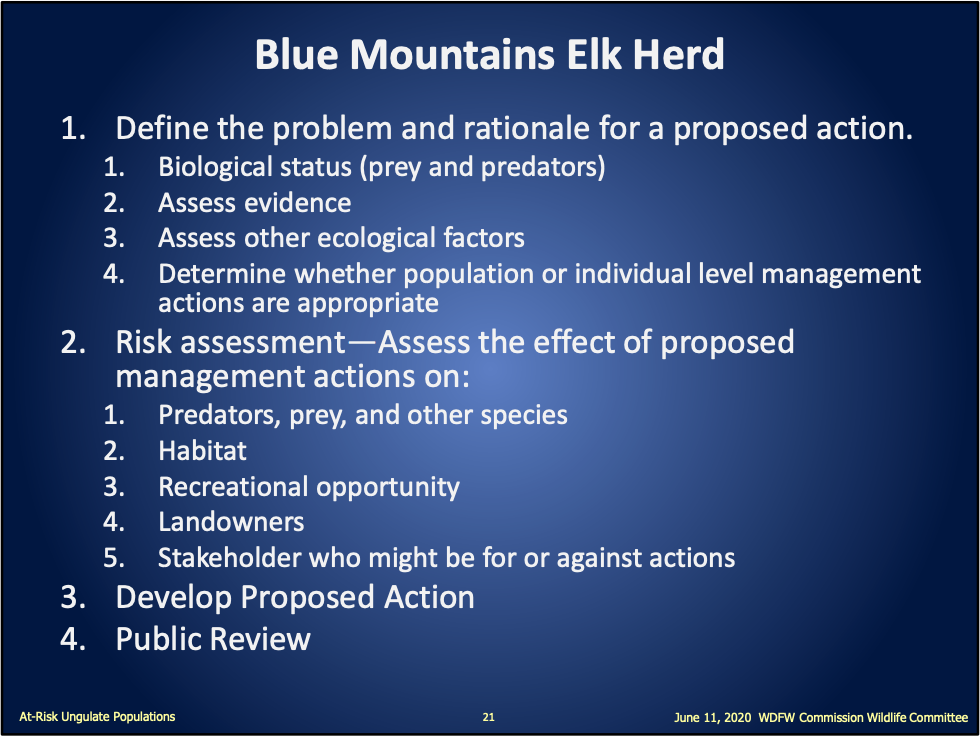

THERE’S A SECOND FRONT TOO. WDFW is performing an assessment of the “literature” – the copious research that’s been done on elk in Washington’s as well as Oregon’s Blues by the states, US Forest Service and biologists like the Cooks, plus other places where the same suite of predators and elk exist, along with a look at local herd demographics and predator densities – as a step towards possible predator control.

That is called for in WDFW’s July 2015-June 2021 Game Management Plan.

Management of predators to benefit prey populations will be considered when there is evidence that predation is a significant factor inhibiting the ability of a prey population to attain population management objectives. For example, when a prey population is below population objective and other actions to increase prey numbers such as hunting reductions or other actions to achieve ungulate population objectives have already been implemented, and predation continues to be a limiting factor. In these cases, predator management actions would be directed at individuals or populations depending on scientific evidence and would include assessments of population levels, habitat factors, disease, etc

–July 2015-June 2021 Game Management Plan

Some of that biological information can be found in recent agency documents.

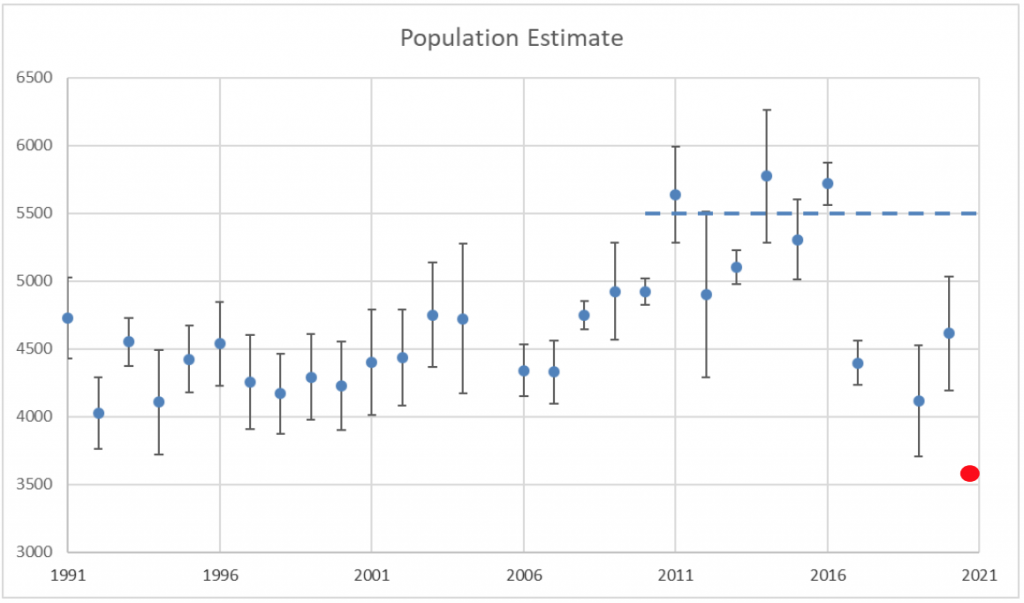

A Fish and Wildlife Commission presentation from this March estimated the Blues herd earlier this year numbered just 3,600 animals, the fewest surveyed since 1991, and 35 percent below the population objective of 5,500.

The decline began during the very harsh winter of 2016-17, when the herd dropped steeply from around 5,700 animals to 4,400, then wilted further to 4,100 in 2019. While on paper it rebounded to 4,600 in 2020, that might actually have been “partially related to a group of elk being in the survey area that also spends time in Oregon and was not observed in 2019,” according to WDFW.

Now herd numbers are as low as they’ve been since the Gulf War, if not even further back.

While the ratio of bulls per 100 cows is currently meeting expectations of 25:100, calf recruitment rates of 17-25:100 cows since 2017 have been “poor to marginal,” pointing to that part of their life history as the problem area and why the herd is struggling to rebuild itself in recent years and hunter harvest has dropped.

A June 2020 briefing of the state Fish and Wildlife Commission’s Wildlife Committee on at-risk deer and elk populations in Washington shows calf recruitment rates were as low as 11:100 cows in Grande Ronde, GMU 186; 15:100 in Mountain View, GMU 172; and 19:100 in Tucannon, GMU 166, last year.

For riflemen, bowmen and muzzleloaders, the Blue’s big bulls are one of the most coveted hunts in the land, but the harvest has seen a “significant decline” since 2015, when 268 antlered and 136 antlerless elk – 404 total – were taken during general and permit seasons, according to this March’s commission presentation.

Last fall saw just 159 bulls and 41 antlerless elk – 200 – killed, the latest records show, again a function of a smaller herd and reduced antlerless opportunities.

Blue Mountains elk are also hunted by the Nez Perce, or Nimiipuu, and Umatilla Tribes through treaty-reserved rights.

But there’s more to the equation.

“To do any predator management, that means assessing beyond what hunters take. We have to ascertain that predators are preventing the population from reaching its potential,” Aoude said.

This spring’s collaring of the 125 calves will give WDFW a chance to compare survival and predation rates with research from the pre-wolf era.

The Blue Mountains Elk Herd Plan (2020) notes that a 1992-98 study by WDFW’s now-retired Woody Myers found that 113 of 240 calves – nearly half – didn’t reach a year old, with 48.6 percent of their deaths attributed to cougars, 15.9 percent to black bears, 15.8 percent to “undetermined causes,” 8.4 percent to “unidentified predators,” 4.7 percent to coyotes, 4.7 percent to hunters and 1.8 percent to accidents.

During those years, the herd was also below objective, but not nearly as far underwater as it is today.

The plan reports that a cougar research project that wrapped up in 2013 found densities of 3.02 mature cats per 100 square kilometers, or 38.6 square miles, in the Blues, “considerably higher than reported elsewhere in the state of Washington, which averaged 1.5 – 1.7 adult cougars/100 km.”

And it also mentions a 2002 ODFW elk predation and nutrition study of 460 calves in two units just south of the state line, Wenaha and Sled Springs. Again, around half died in their first year, and predators were responsible for 214 of 232 documented deaths – cougars: 169, or 75 percent; bears: 33, or 15 percent; with the remaining 10 percent attributed to unidentified predators (nine), unknown (eight), humans (six), disease or abandonment (four), coyotes (two) and bobcat (one).

The WDFW summary of that work states, “The data indicated that predation by cougars limited recruitment of elk calves; the authors predicted that calf recruitment would increase if cougar populations were reduced. However, they suggested that the high predation rates observed may mask nutritional limitations, and predation may be at least partially compensatory, meaning calf recruitment may also be constrained by inability of habitat to meet nutritional requirements of calves prior to winter.”

With those 125 radio collars, WDFW biologists will not only be able to track the seasonal movements of calves but get to carcasses quickly once a device sends off a mortality signal, giving them time to do a postmortem that will help determine the immediate cause of death and provide details on the relative health of the elk at the time of its demise.

Obviously there’s zero doubt predators are taking their toll on elk – bears right as calves drop; cougars and wolves the rest of the year – as they always have and always will, but nutritionally poor habitat can make calves an even easier target for them, research touched on in the herd plan.

“If they’re born weak, they’re more susceptible to predation,” Aoude said.

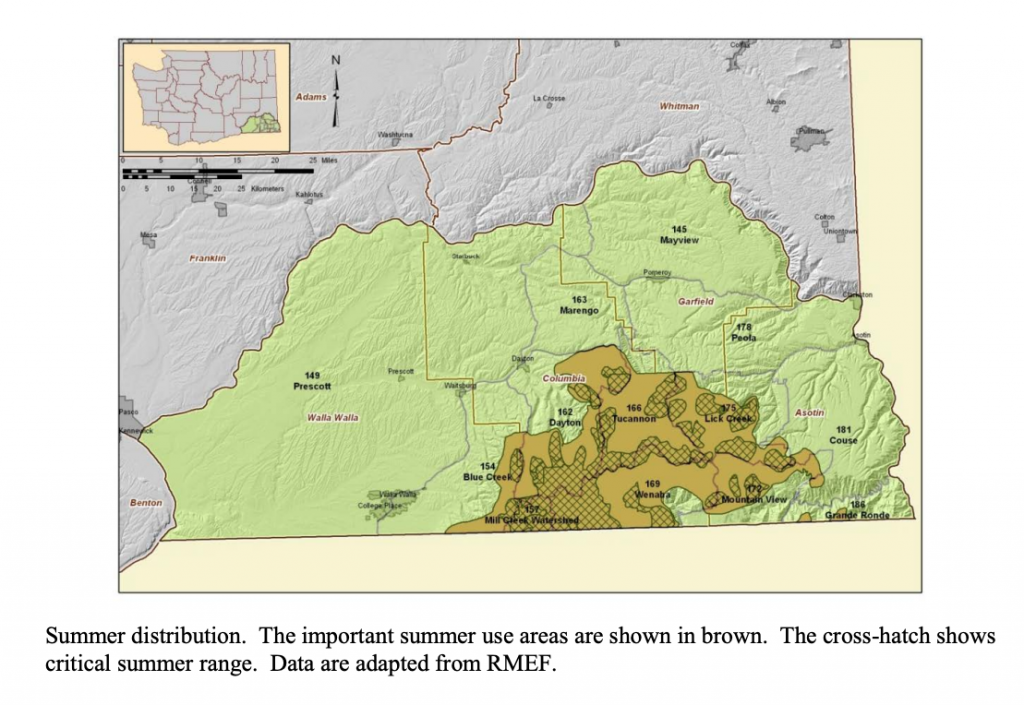

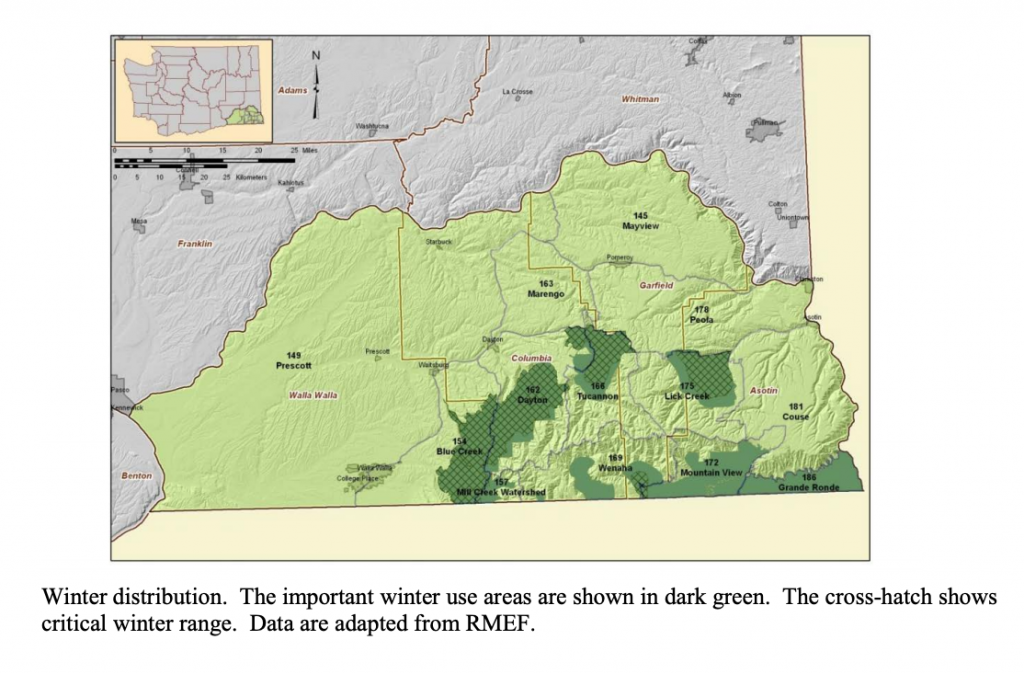

Calf birth health is a function of summer and fall range condition impacts on their mothers and whether they even come into estrous. If conditions are good, all cows come into estrous; if they’re poor, only older ones – a smaller relative portion of the breeding population – do, depressing herd productivity. Winter range is also important in terms of the late-gestation health of cows.

Their nutritional levels the previous summer and fall also impacts calf birth timing – earlier and all together at once is better for dealing with predation than later and out of synch – and how heavy or robust calves are when born. Those without that “spring in their step,” as Aoude put it, are at higher risk of being eaten.

Then there’s human disturbance during calving time, with more than 10 encounters above normal amounts reducing a cow’s reproductive success. That’s the reason for winter range closures.

Aoude says that nutritional studies have shown elk in the Blues across both states “are not generally in great condition.”

“They’re kind of skating by. Get some bad years and it’s easy for them to slip,” he said.

ONCE THE “TABLETOP EXERCISE” of that literature assessment is done, it might lead state wildlife managers to try an experiment, Aoude said.

Will predator control reduce calf mortality and help rebuild the herd? If that course is taken in one to three years, it would be a big step for WDFW.

“I don’t think we’ve done it on the scale of a herd,” said Aoude.

In his recollection it’s only been performed with individual cougars impacting small populations of bighorn sheep.

“We have gone in and removed specific cougars, but nothing really on a scale like this,” he said.

The statewide game plan says if WDFW decides to go that route, it would be done via hunting seasons, specific licensed hunters/trappers, USDA Wildlife Services or agency staff.

First, however, biologists and managers have to figure out if it is warranted in the case of Blue Mountains elk calves.

“We don’t know yet,” Aoude said.

If it is, he said only the main predator species would be targeted, he said.

“It’s unlikely it’ll come out to be wolves,” Aoude added. “Wolves don’t usually end up being the limiting factor.”

Another furry fanger seems to be the undisputed holder of that title in the Northwest.

A 2016 paper from a Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks researcher looking at the Bitterroots reported that “Despite the recent recolonization of the study area by wolves, mountain lions caused more elk calf mortality than wolves in summer and winter.”

A synthesis of 15 years of wildlife data in Idaho by IDFG “found that wolves accounted for 32% of identified mortalities for female elk while mountain lions accounted for 35%. That disparity grew when looking at elk calf survival with wolves accounting for 28% of known-fate deaths and lions accounting for 45%,” Eli Francovich at the Spokane Spokesman-Review wrote in 2019.

In the Blues, a higher ratio of calves is lost between September and March than in winter, according to Aoude and that June 2020 presentation, pointing the finger in the direction of predation and specifically cougars, given their proclivity for deer-sized prey.

STILL, IT WILL BE INTERESTING TO FIND out if the elk calf work being done here over the next year replicates Idaho and Montana findings, or turns up something else. It is a different landscape with different challenges.

While I’m definitely no wildlife biologist, if I had to bet a nickel, I’d put it down on cougars as the primary predators here and I’d venture a second five-cent piece that predation rates are somewhat above what that 1992-98 WDFW study found, with wolves now taking a solid bite, though, again, not a larger one than lions.

I’d also hedge my bets by throwing a dime down on habitat issues causing strong nutritional stress for mama and baby elk, with cougars, wolves and bears subsequently taking advantage of that, depressing herd numbers and productivity and turning this into something of a nutri-dator pit.

“It’s complicated. Everybody wants it to be one thing and it’s never one thing,” said Aoude. “If we see predation is the issue, we can mitigate that, but not for a long period.”

That’s an expensive proposition, as IDFG’s Mark Hurley and other ungulate researchers have stated.

The long-term solution is better habitat for the elk.

I don’t hunt the Blues for wapiti, but as a Washington hunter I do appreciate WDFW going to these lengths – the calf capture-collar project and the literature assessment.

Given how incredibly sensitive all things Evergreen State predator have become – witness the ridiculous spring bear and wolf lawsuits, advocates endlessly pressuring the governor on wolves and cougars, a certain commissioner recently seemingly trying to derail bear seasons for no good reason – they absolutely must have a solid scientific base should control actions be taken.