Lawsuit Over SE AK Salmon Fisheries Also Targets Orca Prey Increase Program In Puget Sound, Elsewhere

The lawsuit targeting authorization of Southeast Alaska salmon fisheries in federal waters has been well covered.

Not so well known is that it also asks a US District Court judge to stop a $5.6-plus-million annual program that’s been launched to increase hatchery Chinook production in Puget Sound and elsewhere in the Northwest and is meant to benefit starving southern resident killer whales.

Today marks the deadline for parties in Wild Fish Conservancy v. Barry Thom et al, Alaska Trollers Association and State of Alaska to have submitted their arguments and motions for consideration by Magistrate Judge Michelle L. Peterson in Seattle.

Hundreds upon hundreds of pages of declarations and responses from both sides have been entered into the official record in recent days and weeks for the case originally filed in March 2020.

Thom is the National Marine Fisheries Service’s West Coast administrator and his agency’s 2019 Southeast Alaska Biological Opinion is under fire from the highly litigious Duvall-based organization, infamous for going after WDFW and hatchery steelhead.

With WFC openly stating it wants to “halt” salmon harvest up north to save orcas down here, news coverage of their lawsuit has naturally primarily focused on the potential economic impact to the Alaska panhandle.

Fisheries and jobs there generate “on average $806 million in output, $484 million in gross domestic product, $299 million in labor income or wages, and 6,600 full time equivalent jobs,” state officials said when they were granted a motion in March to stand alongside NMFS in court.

They’re at risk because the biop “delegates” harvest management from 3 to 200 miles offshore to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Those rich waters draw Chinook and other stocks from Washington, Oregon and British Columbia rivers, fed on in turn by SRKWs.

Meanwhile, down here in the Northwest, the additional king smolts being released under NMFS’s biop for return in three to five years are meant to help sustain orcas in the short-term while long-term habitat work like dam removals and estuary restoration hopefully lead to increased wild fish populations. One estimate says it will take 90 years at the current pace to recover Puget Sound’s critical-for-Chinook nearshore marshes.

The extra hatchery fish should also provide opportunities for sport anglers, and tribal and commercial fishermen alike.

But that’s under threat as WFC asks Judge Peterson not only for a summary judgment declaring the biop to be in violation of the Endangered Species and National Environmental Policy Acts and that it be vacated, but to “enjoin NMFS’s implementation of increased hatchery production,” which they say poses a threat to wild salmon and wasn’t evaluated for that possible effect.

The organization essentially contends that the biop’s argument that Southeast Alaska’s fishery wouldn’t jeopardize Washington’s orcas because it would be mitigated for via hatchery production “lacks specific and binding plans” and “is not subject to NMFS’s control or otherwise reasonably certain to be fully and timely implemented.”

The feds disagree and say that increased releases are being done “in a thoughtful and careful manner” that includes “site-specific ESA and NEPA evaluations,” ensuring that it “is not resulting in irreparable harm to ESA-listed salmon, while providing benefits to endangered SRKW,” according to a 194-page declaration from Allyson Purcell, who heads up NMFS’s regional hatchery and inland fisheries division.

“The prey increase program is a critical tool to help address a primary threat to SRKW and without it there will be a negative impact on the recovery program for SRKW,” warns NMFS’s Lynne Barre, chief of the agency’s protected resources branch.

In court filings this afternoon, the state of Alaska argues “the prey increase program is expected to increase prey by a greater amount than the SEAK fisheries potentially reduce prey” (emphasis theirs).

Barre’s declaration notes the program is part of a “comprehensive” suite of short- and long-term measures being taken to help rebuild J, K and L pods.

Salmon overseers have also already turned down the fisheries dial. Sport and commercial seasons up and down the West Coast have been reduced over recent decades, sharply in some cases, but whale numbers still plummet. Some point out their decline matches up linearly with a drop in hatchery salmon releases over the same period.

A federal proposal now out for public comment would restrict primarily nontribal commercial fisheries off the West Coast but some terminal recreational fisheries when preseason forecast abundances dipped below 966,000.

Meanwhile, all-encompassing ridgetop-to-seafloor fish habitat alterations, increased marine mammal predation, as quantified by Chasco et al, and warming seas, are keeping wild populations from bouncing back or much at all.

“We concluded that the proposed actions were not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of SRKW or their ESA-listed Chinook salmon prey or destroy or adversely modify critical habitat for SRKW and the listed salmonids,” Barre says of the biop in her declaration.

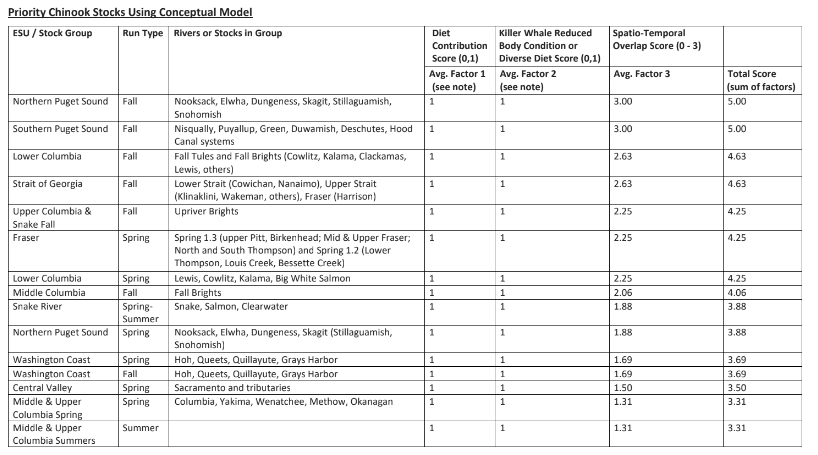

Backing up a bit, with the lack of abundant salmon to feed on one of three key factors impacting the southern residents, in June 2018 Barre and colleagues identified which Chinook runs were most important to them – Puget Sound, Lower and Upper Columbia and Snake River falls, Lower Columbia springers, Mid-Columbia falls, Snake spring/summers.

As the orca known as Tahlequah pushed her dead baby around Puget Sound that same summer, Washington Fish and Wildlife Commissioner Don McIsaac pitched producing 50 million more smolts.

That might have been a moonshot, but in 2020, Congress did earmark $5.6-plus million to rear extra Chinook as part of a $35.1 million package implementing a new Pacific Salmon Treaty with Canada and which also mandated further reductions in Southeast Alaska and West Coast Vancouver Island fisheries.

And in 2019, following recommendations from Governor Inslee’s orca task force, Washington lawmakers provided $13 million to increase salmon abundance for SRKWs, with WDFW boosting production by 25 million smolts, and this year they continued that level of support from state coffers.

According to NMFS, as a result of the funding from Congress and the Legislature, 11.6-plus million hatchery Chinook above pre-2019 base levels were released in 2020, including 6 million from Puget Sound facilities, and another 18.3 million smolts are expected to be let loose this year.

The expectation is that 4 to 5 percent more Chinook will be available for the whales to forage on in Puget Sound in summer and offshore in winter.

As for what those federal dollars paid for this year and which are at risk moving forward, the list includes 2 million extra fall kings from WDFW’s Soos Creek Hatchery on the Duwamish-Green River, 2 million tule Chinook from USFWS’s Spring Creek Hatchery in the Columbia Gorge, 1.4 million spring Chinook from Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife off-channel sites in the Columbia estuary, 1 million summer kings from the Tulalip Tribes’ Bernie Gobin Hatchery, 650,000 fall kings from USFWS’s Little White Salmon Hatchery on Drano Lake and 500,000 summer kings from Douglas County (Washington) PUD’s Wells Hatchery on the Upper Columbia, among others.

Looking at that list, Central Sound, Tulalip Bubble and Columbia anglers could enjoy what McIsaac once described as “shirttail benefits” in coming years.

But it’ll be up to Judge Peterson whether the program meant primarily to boost Chinook numbers for the orcas continues after that.

WFC wants it halted “until NMFS prepares a BiOp that complies with the ESA for this program and completes required NEPA procedures,” according to court papers.

The question is, do the SRKWs have that sort of time?

Stay tuned.