Washington Coast Steelhead Forecasts, Fishery Proposals Out

Washington Coast steelhead managers rolled out forecasts for winter-run streams from Raymond north to Forks and asked anglers for their feedback on initial fishery proposals during a two-hour virtual town hall Tuesday evening.

It was a tough presentation that showed many wild stocks are expected to continue to struggle after 2020-21’s “lowest on record” overall return, but also part of an ongoing WDFW attempt to engage stakeholders much earlier in the process than last season, when the Fish and Wildlife Commission was caught off guard.

If there was any good news out of yesterday, it was that even as escapement goals weren’t met on five of seven systems, the widespread showing of older, larger, repeat-spawner steelhead did give managers hope of a more productive run than smaller fish would have yielded.

And even though things do look grim for the Chehalis, 2021-22 options are still on the table.

“I think it is too early to arrive at any conclusions,” Kelly Cunningham, WDFW Fish Program director, said this morning. “We still have a lot of work to do with our co-managers and analysis of the proposals we heard last night.”

It’s all fodder for local, fishing and conservation communities to mull ahead of two more town halls, agency meetings with tribal comanagers, a November 19 commission briefing and WDFW’s final decision on the season.

That’s a hugely important one given that the crown-jewel fishery provides a key economic boost for towns like Forks, guides and by extension even this magazine at an otherwise slow time of year for them, as well as rumblings last year of an ESA proposal.

“Don’t dilly-dally,” Cunningham urged the 155 attendees who were on the Zoom call that was also carried live on TVW. “If you’ve got ideas for fishery proposals, put them out there.”

Here’s where to share your input.

As it stands, WDFW’s preliminary forecast is for an overall runsize of 26,336 wild steelhead this winter and spring.

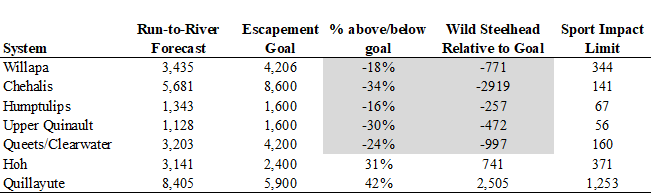

That figure includes 8,405 fish to the Quillayute (42 percent above escapement goal), 5,681 to the Chehalis (34 percent below), 3,435 to Willapa Bay rivers (18 percent below), 3,203 to the Queets/Clearwater (24 percent below), 3,141 to the Hoh (31 percent above), 1,343 to the Humptulips (16 percent below) and 1,128 to the Upper Quinault (30 percent below).

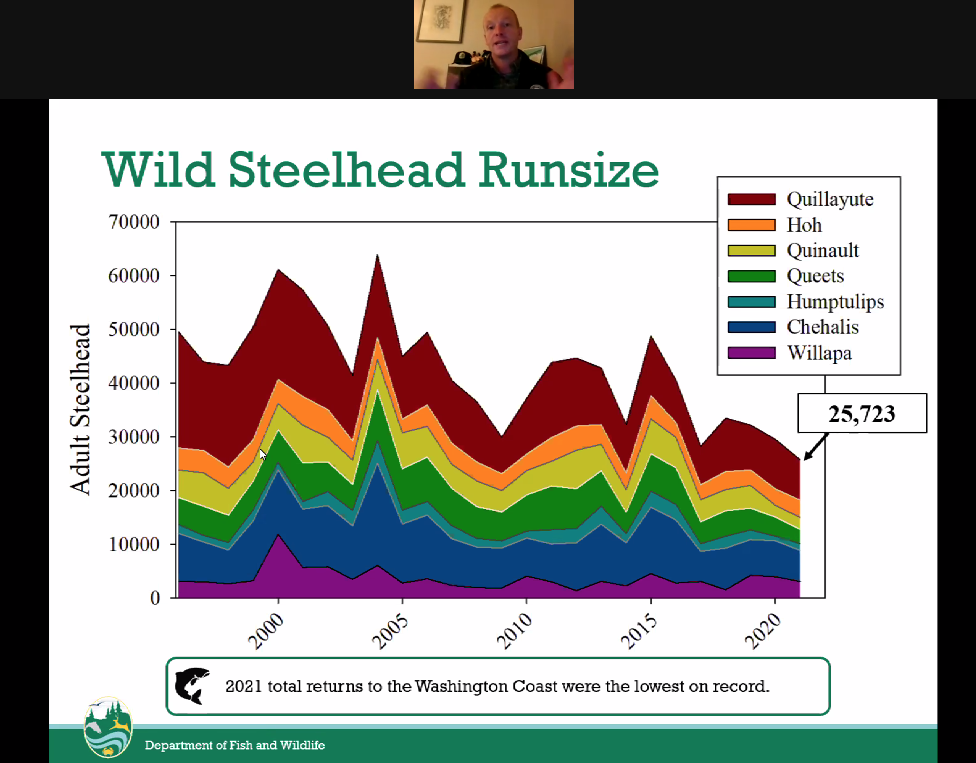

At roughly this same point in the process last year, WDFW expected 28,995 wild steelhead to enter those rivers, but 14 percent fewer did, an estimated 25,723.

Given this season’s forecast and factoring in 50 percent tribal shares where applicable and 10 percent mortality caps on sportfishing impacts from the statewide Steelhead Management Plan for streams not expected to meet spawning escapement goals, WDFW says there are allowable mortalities of 1,253 fish on the Quilly, 371 on the Hoh, 344 on Willapa tribs, 160 on the Queets/Clearwater, 141 on the Chehalis, 67 on the Hump and 56 on the Upper Quinault.

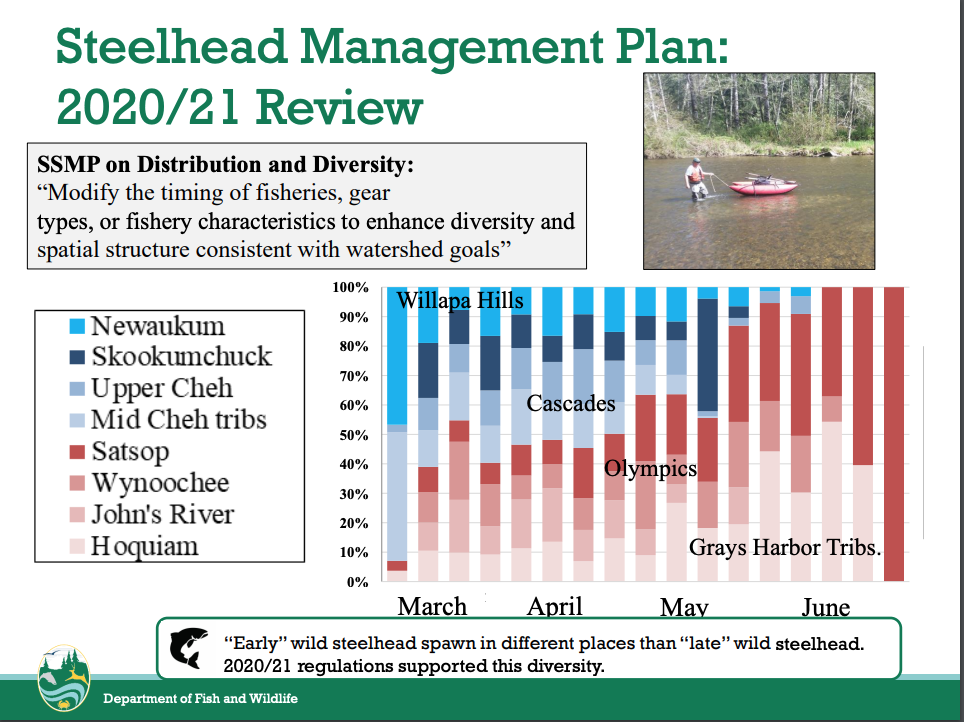

Fishery proposals are being weighed against fish abundance, productivity, distribution and diversity.

Just applying 2020-21’s unprecedented blanket regs – no boat fishing, plus bait and barbed hook bans and other measures – would lead to closures on the Chehalis, Humptulips, Upper Quinault and Queets/Clearwater this season, one agency graphic suggested.

But pairing those restrictions with “reduced days” – which WDFW last night defined as “open 1 to 3 days a week” – might yield some form of fisheries on most systems.

That would maximize time on the water, spread effort, provide generally consistent protection for the fish and allow anglers to tap into early and late hatchery fish.

But it could also come at the cost of displacing some users, present an enforcement headache and potentially focus impact on early wilds if there’s an emergency closure.

James Losee, WDFW’s coastal region fisheries manager, worries about continuing if not worsening returns in the future due to adverse conditions young fish have been facing when entering the Pacific.

“When the ocean’s cold, they perform better than when it’s warm,” he said.

During public input last night, anglers focused on reinstating some sort of boat fishing opportunity, the most effective way to catch wild steelhead.

Limiting fishing to bank only last year reduced landings by an estimated 56 percent and doubled the time needed to catch a fish, WDFW estimated, yet still allowed several months of on-the-water opportunity.

Brian McLachlan asked managers to consider opening select stretches of certain rivers at specific times so that youth, senior, disabled and other physically challenged anglers could fish from a boat.

Pointing to his 70-year-old brother, he referenced how difficult it can be for some to get in and out of a drifter and navigate the rocky shores of coastal rivers all day long, and he pointed to WDFW’s statutory mandate to provide opportunity while meeting conservation needs.

As an example, McLachlan suggested allowing them to fish from a boat on the Bogachiel from the state hatchery at the confluence of the Calawah downstream to the Wilson access, a key stretch for intercepting early-returning fin-clipped steelhead.

“I like that, a more nuanced approach,” responded Losee, who indicated he would “dig deeper” into the proposal.

Last year the idea that disabled anglers should have an exemption from the boat ban was a surprisingly firm no from WDFW, with terminally ill fishermen the only possible exception that would be considered.

Chase Gunnell asked about a hybrid model where boat fishing might be allowed early in the season and then phased out later.

Losee said it would have a “disproportionate” impact on the smaller early segment of the wild run, but he would look into whether anglers were interested in a tradeoff like that.

Larry Gillard asked about allowing boat fishing but with bait and barbed hook bans on the Quillayute and Hoh, which are again both expected to meet their escapement goals.

Losee said it was possible on the former, though it might result in a poor quality experience given likely crowding. His presentation also noted tribal concerns, meaning preventing overlapping fishery days, a restriction being increasingly applied.

But for Rich Simms, the boat in question was the one WDFW “is missing.”

“These fish are in crisis and here we are discussing how we can scrape a season out of it,” Simms said. “What we have to realize, these fish, we gotta be serious about doing whatever we can to protect as many of them as we can. We’re down to not just trying to split crumbs, but potentially we’re not going to have a fishery in the future.”

And Jonathan Stumpf warned that the discussion was based around “paper fish” and he said that extra steelhead needed to make it to the spawning grounds.

There were also questions about WDFW’s data and application of Hoh catch stats to other systems, whether the “alarming rate” of poaching is being accounted for, and a call for the tribes and state to not fish till escapement goals are met.

Losee applauded the concept of a “shared goal” with the tribes even as his charts and graphs showed that steelhead run and spawn timing spans such a wide timeframe that all it would essentially do is protect the early part of the run to the detriment of the latter. That fluvial calendrical breadth is one of the species’ strengths as it struggles to survive a changing world.

But as long as we’re speaking about the tribes, last night Losee was also able to share data that showed treaty harvest last season was “significantly lower than expected” as the comanagers, like WDFW, scaled back their fisheries in response to the low forecast.

He said their overall catch was 34 percent below initial projections, with 1,784 wild steelhead reported landed against a preseason forecast of 3,560, and 2,709 hatchery fish landed compared to a projected harvest of 6,921.

Asked about the root cause of the coast’s low returns, Losee pointed to environmental conditions that are worse for steelhead than they were in the 1980s, a time when he said fisheries could occur even with poor returns thanks to “really productive” freshwater and ocean waters that made up for it.

“The way we fished in the past doesn’t look like it will work” today, he maintained.

Gillard, the angler, wanted to know what could be done to protect smolts and adult steelhead in the form of controlling diving birds and seals.

ODFW has hazed cormorants on coastal bays to reduce predation on young salmon.

“I liked how you just said, ‘what we can do,'” replied Losee. “To answer the diving bird question, I’m not an expert on the effect that would have on steelhead, but what I do know and the literature supports this and we’ve seen this with important habitat projects: We can’t control ocean conditions, but we can control the way fish interact with the ocean by raising wild fish that are bigger and more fit and have productive freshwater habitats. So what we want is more juveniles moving into the ocean and we want those that are extremely fit, so they occupied really healthy habitats early in their life. We’ve seen that is probably, short term, the best fix here, and long term, is to improve our freshwater habitat.”

Gillard also said he would like to see broodstock programs pushed more.

Losee replied that WDFW is brainstorming new hatchery efforts, but noted that conversely, the need to collect broodstock for Chehalis winter steelhead programs also means fewer are available to support sport fisheries.

It took me awhile to track it down in my notes, but one thing Losee said really resonated. He was talking about the simplest solution, just shutting the fishery down for the season, and the pros and cons therein.

“This is real and something we believe in is that if we’re going to recover wild steelhead and move them sort of into a positive trajectories, we need anglers’ help. These are the folks that interact with them the most,” he said. “So that’s [coastwide closure] a major con.”

It appears that WDFW is making a remarkable effort to come up with defensible fisheries and talk to the public about them, while also making clear the conservation challenges the fish face.

Doing both strengthens the bond all the more.