Video Shares Ongoing ‘Predator-Prey Project’ Work In Okanogan, Northeast Washington

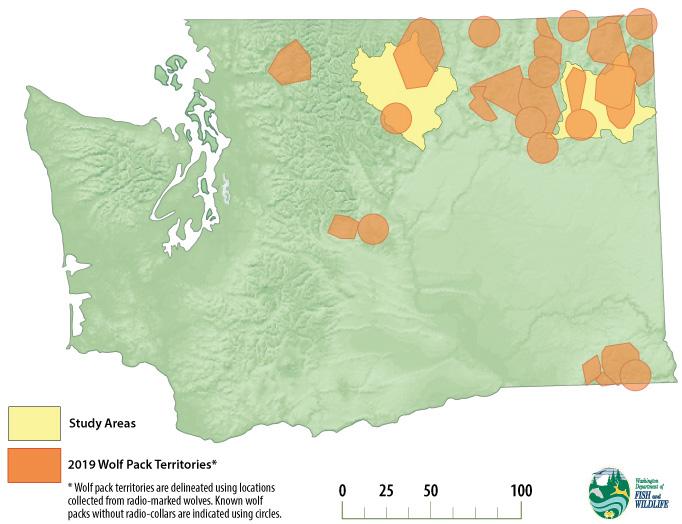

A video on the state’s Predator-Prey Project, a legislatively mandated effort to figure out the impacts of wolves and cougars on deer, elk and moose – as well as each other – in portions of northern Eastern Washington, was debuted by WDFW today.

The 13-minute film features the darting and GPS-collaring of a pair of the lead actors, similar capture of does, and mortality investigations in the cutover woods and mountains around Twisp and Colville, some of the Evergreen State’s most revered hunting grounds.

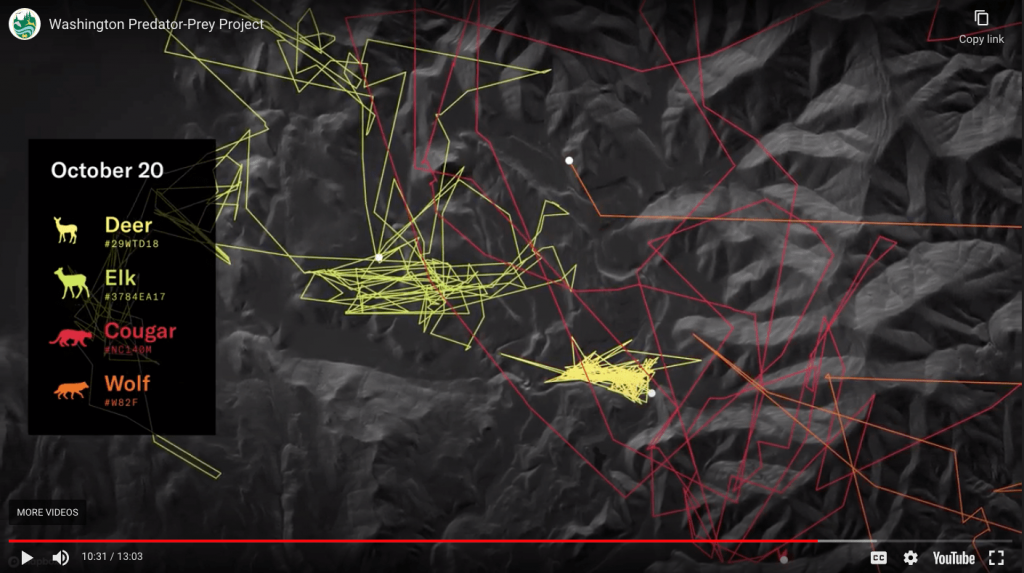

Mixed amidst time-lapse trail cam videos showing how highly trafficked these “managed” landscapes can be by four- and two-legged critters alike is mapping based off GPS collar data that reveal the overlapping movements of a home-bodied deer, flighty elk and footloose cougar and wolf one fall.

And it features agency biologists and University of Washington researchers talking about their work and goals, and a state lawmaker at his ranch between study zones and who hopes it finds a balance between predators, prey and people.

Essentially it’s a video update on a five-year project that began in 2016 that attempts to show the science work being done to answer pressing questions from the public about Washington’s newest predator and its prey, but its soaring aerials and musical notes, slo-mo shots and close-ups also signal that eagerly awaited results are not on offer quite yet. Those aren’t expected to begin being published until next year.

As a Washington hunter whose mule deer grounds since the mid-1990s are included in the western portion of the study, I’m both very pleased that biologists are doing this work – not to mention keenly interested in what they find – and glad the agency is putting out more base information on the project.

It’s mostly been the subject of dry news releases, blogs here and there, a peppering of stats (it’s involved 460 mule deer, whitetails and elk so far, 100 trail cams and 150 “AudioMoths”), and a commission presentation or two.

For a long time the primary focus on wolves in Washington has been on livestock conflicts, because, well, even if 80 percent of packs stay out of trouble, 20 percent are going to depredate, impacting ranchers, and that requires management, and that naturally attracts a whole lot of attention.

Lord knows I’ve done a blog or two on lethal removals, protocols, court cases, etc., etc., etc.

But wolves have also been a building topic around our fall deer camp’s fire, and those of many fellow hunters. One partner did hear distant howls while on the mountain, and I might have one night too, though it could have also been a figment of a half-asleep head. Others in Washington have had encounters of far closer kinds.

Where I’ve been focusing my hunting of late I suspect that wolves won’t do well because the topography and land cover doesn’t favor their style of pursuit … but maybe their presence just means cougars will set up ambushes there more often instead. Or maybe they will chase the big cats off of their kills and require them to take down another mule deer sooner than they otherwise would.

I wonder, how a theoretically less selective killing technique like ambushing will play out in the herd over time versus testing over distance for weaker animals?

Maybe it will all be a wash and the certain number of deer that are just going to die by one set of fangs will die by another instead. What wouldn’t be a wash, I worry, would be a prolonged snowy winter that made weakening ungulates easier pickings and leading to a deeper bite out of the herd than otherwise might be expected.

But how does habitat quality and fragmentation play into all of it? It’s a bumper sticker, but an accurate one: Habitat really, really, REALLY is the key for our big game herds.

Those are the kind of questions researchers are asking.

“We want to understand wolf-cougar interactions. Are wolves and cougars using these same areas or not? Are they competing for deer and elk in the same places or not? That is really one of the unanswered questions,” explains UW’s Lauren Satterfield in the video.

I don’t know that the Predator-Prey Project will answer questions about my hyperspecific hunting locale – and of course as the deer make their annual rounds, they also use areas more conducive to wolf predation – but my wolf-dar is perpetually sweeping for any news from the area or any insights.

Leading into fall 2018’s general season, I wrote about what another study of Northcentral Washington deer and wolves had turned up:

[JUSTIN] DELLINGER’S RESEARCH OCCURRED in eastern Okanogan County and on the Colville Indian Reservation and involved mule deer and whitetails. Frankly, I assumed that only the former species occupied the same sort of ground as wolves – mountainous national forestlands – but Dellinger’s hypothesis is that the long-legged predators’ territories actually overlap more with valley-loving whitetail.

“Wolves run – that’s how they catch their prey,” he states, and they can do that better in areas of rolling, gentle terrain than the “steep, rocky stuff” that mule deer prefer in this particular country.

But muleys and wolves also occur on the same landscapes, and there the deer generally try to avoid contact with the wild canids because their defensive strategy – stotting off a short ways when confronted with danger – is easily defeated. Thick, rough country “where wolves have to run around obstacles” works better for them, Dellinger says.

“They’re shifting to steeper, more rugged terrain,” he says of mule deer, “getting further away from Forest Service roads, which wolves use as travel corridors, and they’re using areas of more increased cover.”

That’s going to make it more difficult for some of us to hunt these deer, and anger and accusations that the herds have been decimated may follow.

But as more and more wolves and packs occur in the state’s whitetail heartland, that deer species’ reaction is almost the polar opposite. “They’re selecting for areas with greater visibility, away from cover and out in the open, areas of decreased slopes, closer to roads,” Dellinger says. Those all help whitetails detect wolves early, allowing them to get a head start and “run like a bat out of hell,” he says.

That tactic didn’t work out for two study does, though, according to a recent Dellinger paper. It builds on previous research by Washington State University that pegged wolves as the “probable” reason why 137 deer died over the course of a two-summer study in much of the same region. That work was based on collars on wolves and cattle, but Dellinger et al did the opposite, putting telemetry on 120 deer – bucks and does, whitetails and mule deer – in wolf and nonwolf areas. That allowed them to follow up when the devices gave out mortality signals. They were able to determine the cause of death for 38 deer, with humans accounting for 16, cougars 12, coyotes seven, unknown three, wolves two and bears one. Lions preferred does (10) while hunters went for bucks (13). It’s easy to over-read the data as suggesting wolves don’t prey much on muleys – packs don’t keep settling in the Kettle Range just to eat beef in summer – but that doesn’t mean they’re not having other impacts. The big-eared bounders’ shift to more rugged terrain just puts them deeper into cougar country, Dellinger notes.

– Northwest Sportsman, October 2018

So it will be interesting to see if the Predator-Prey Project confirms those findings or discovers differences, further informing me and other hunters how much we need to adjust our tactics. And I’ll be curious to see how it compares to similar work being done in North Idaho.

Meanwhile, I’ll be viewing one of the researcher’s recent presentations, “Ungulate Responses to Predators in Complex Landscapes of Northern Washington” so I can learn from it as well.

And scrounging through WDFW’s various big game documents – season proposals; harvest reports; annual trends – for any signs of predation impacts on deer, elk and moose. Here’s what they’re telling the Fish and Wildlife Commission this week as the citizen panel prepares to OK 2021-23 hunting seasons:

On deer and elk:

WDFW’s Game Management Plan identifies guidelines to determine when a particular population meets the criteria of an “at-risk” ungulate population and whether carnivore management actions are needed to promote recovery. In some areas, populations meet that criteria and we have initiated efforts to determine if carnivore management actions are warranted. In addition, we have liberalized bear and cougar hunting seasons in eastern Washington in response to concerns that carnivore populations are too high.

https://wdfw.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2021-03/14_deer_general_seasons_ss.pdf

On moose:

WDFW’s Game Management Plan identifies guidelines to determine when a particular population meets the criteria of an “at-risk” ungulate population and whether carnivore management actions are needed to promote recovery. None of our moose populations currently meet that criteria. Moreover, recent findings from research conducted in GMUs 117 and 124 indicated poor calf survival and declining populations in both GMUs, despite the fact there were no documented wolf packs in GMU 124. Other findings from that research indicated adult female moose were in poor body condition, indicative of poor habitat conditions, and some moose were suffering from severe tick infestations. Thus, moose in these two areas are likely experiencing declines because of both topdown (predation) and bottom-up (habitat) effects. Lastly, we have liberalized bear and cougar hunting seasons in eastern Washington in response to concerns that carnivore populations are too high.

https://wdfw.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2021-03/13_bighornsheep_moose_mtgoat_ss.pdf

Anyway, WDFW and UW aren’t doing the work for just me and other hunters, but to inform ranchers like the aforementioned legislator, rural residents and the rest of the state’s population alike as wolf populations near recovery goals.

“That’s I think the biggest thing that can come out of this,” says Rep. Joel Kretz (R-Bodie Mountain), “the balance between predator and prey and also with the people that live here. And there’s a balance that can be found; we just haven’t got there yet. And I’m hopeful. Guardedly hopeful, but hopeful.”

I’d echo that.

And it’s also building on wolf research in a key way. For decades now, that’s been dominated by storylines that came out of Yellowstone National Park – just add wolves and the natural world is healed, voilà! – a far, far different landscape than the northern tier of Eastern Washington.

“Wolves in Washington are recolonizing in working landscapes. They’re not recolonizing these pristine, parklike settings. They recolonizing areas where people live, where they work, and where they recreate. And so we know that we can’t take the lessons learned from Yellowstone and apply them here in Washington,” notes Trent Roussin, a WDFW biologist, in the video.

And I’d echo that.

Per Eli Francovich at the Spokane Spokesman-Review, WDFW paid roughly $31,000 to filmmakers Benjamin Drummond and Sara Joy Steele to put the piece together, and I’d say it does an effective job at relaying researchers’ ongoing work to the public.

Wolves are here to stay. I don’t know how to put it any other way, my fellow hunters. So figuring out their impacts in a scientific way makes a lot of sense to me. The video is a heads up that that work is underway, and I look forward to chewing on researchers’ results in the coming years. It should be informative in myriad ways.