New Focus On Snake Dams Raises Hope For Salmon, Fisheries, Local Economies

When Buzz Ramsey talks, people tend to listen. I know I do.

For decades upon decades now, the famed cowboy-hatted Northwest angler has been catching salmon and steelhead, tinkering with lures and sharing expert advice with fellow fishermen.

Ramsey retired at the end of 2020 after a long career at Yakima Bait and Luhr Jensen, among others, but he’s not giving up on fishing. No chance of that, no sir.

He recently appeared in a steelheading video in which he and a crew catch a wild winter-run to help power a state broodstock program.

And Ramsey also spoke his mind on camera. After helping deliver that native fish to a livewell back on land, the Klickitat, Washington, resident put his rod down for a moment to talk about Columbia and Snake River salmon and steelhead recovery.

It’s an issue that is back on the front burner as angling and conservation groups see a stellar chance to make headway – “This is our moment, and we need to grab it,” said one regional leader last week – in a comprehensive way that also helps the region’s economy and those potentially impacted by dam removal, goals that are broadly echoed in a plan that a Republican lawmaker is floating behind the scenes.

“IT’S NOT THAT ANY ONE DAM IS SO BAD,” Ramsey says in the 21-minute-long video posted January 20 by Salmon Trout Steelheader. “It’s the cumulative effect of too many, which is why there is talk about removing the four dams on the lower Snake River … Because to get to all that habitat, 70 percent of the remaining habitat in the Columbia River system is in Idaho and they’ve got to traverse eight dams” to access it.

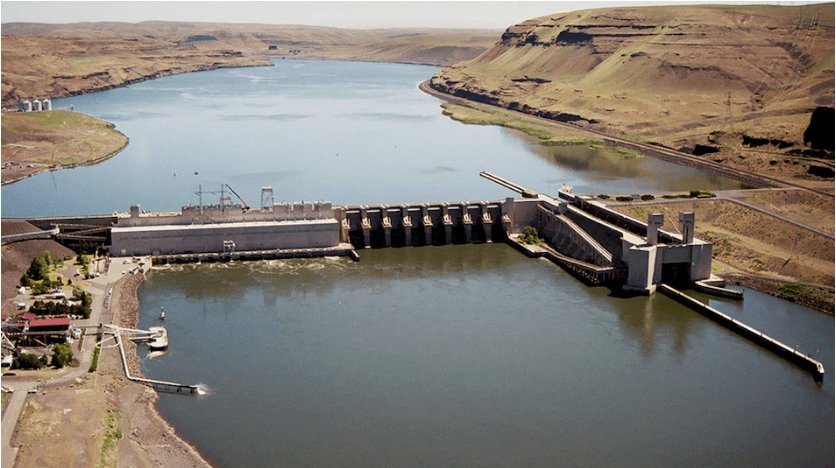

The four dams are Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose and Lower Granite, all in Southeast Washington and built in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s.

Free-flowing-river advocates say they provide just 4 to 5 percent of the region’s electricity, have limited flood-control functions and that only one of their impoundments – the lowest – provides any water for crops.

Yet even as Ramsey maintains the quartet offer “the least benefit to society,” he says the plan to remove them also includes “(making) sure we take care of everybody.”

“In other words,” he says in the video, “we’re not talking about taking those dams out and leaving the irrigators high and dry. No, no. They can still irrigate out of the river; it doesn’t have to be out of the reservoir. So there just needs to be a plan that includes those people so they are left whole.

“If we plan for it, we can backfill the hydropower that is produced by those dams,” Ramsey adds. “If shippers that are shipping stuff out of Lewiston – keep in mind, 80 percent of the commodities that come down the Columbia River are coming out of Tri-Cities, below those four dams; it’s only about 20 percent that comes out of Lewiston – if those shippers up there need subsidized freight, we can subsidize it. The federal government can put together a plan that subsidizes those shipping costs, if that’s what those users need and keep them whole.”

Learn More:

Northwest Strong: Cultivating Alliances on the Columbia and Snake Rivers

Our Northwest Opportunity: Communities, energy and salmon

Chinook, steelhead and other stocks as well as workers would also see benefits.

“This can be just as big of a boon to the region, to where we get federal appropriations to take those dams out,” Ramsey says in the video. “It brings jobs to the region. It’s a jobs project. And it recovers salmon, and part of that plan is to keep everybody whole so nobody is disadvantaged.”

“That’s the vision of recovering salmon,” he says. “Because if we don’t do it, salmon will go extinct. Wild salmon will go extinct. That means that not too long afterwards hatchery salmon will go extinct because you’ve got to – just like we’ve been talking about [with the wild steelhead the crew caught and brought in for broodstock purposes] – dip into those wild stocks to keep those hatchery fish vibrant and working.”

Some $17 billion has been spent trying to recover salmon and steelhead in the Columbia Basin over the past quarter century “with no success,” say dam removal advocates, though Snake River fall Chinook are said to be approaching goal, per a recent Washington report.

“To have salmon go extinct is unacceptable to me and for a lot of residents in this region, it’s unacceptable to them too,” Ramsey says as the segment comes to an end.

SOME OTHERS WHO ALSO FIND THE IDEA UNACCEPTABLE were part of an hour-long Snake River Restoration Panel put on by the National Wildlife Federation and Association of Northwest Steelheaders last Thursday evening.

“The science is clear on a lot of things right now,” said Tucker Jones, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife’s Columbia River fishery manager. “The science is clear that the dams on the lower Snake River and the lower Columbia River are one of the major causes of the decline and really, the biggest current source of direct mortality for these [Endangered Species Act] listed salmon and steelhead from the Snake Basin.”

Some days it seems that every fellow fan of angling in the Columbia system is sure that their particular bogeyman is the singular thing that is responsible for fish woes – terns, walleye, sea lions, tribal nets, commercial nets, harbor seals, cormorants, smallmouth bass, too-warm river conditions, hatcheries, you name it – and that eliminating it would solve all problems like some silver bullet.

But Jones insisted that none of those myriad factors stack up next to the impact of the dams.

“Everything else is, relatively speaking, such a tiny piece of the overall puzzle,” he said, holding his index finger and thumb closely together to illustrate the point.

“Really just looking at the differences of fish that otherwise share the same experience, those fish are going to have the same sea lions chasing them. They’re going to have the same ocean conditions when they hit the estuary plume on their outmigration. They’re going to face the same fishing pressures in the ocean and in the river,” Jones said.

The difference is that “cumulative effect” that Ramsey referred to in the STS video.

“What some of them don’t have to face, and what some of them do have to face, is the number of dams,” Jones said. “And really, every time one of those fish hits one of those dams as a smolt swimming out of the river, it decreases its opportunity of returning as an adult by about 10 percent. Every time. If you have only three dams to pass and you’re unfortunate enough to hit three dams, you’ve basically reduced your chances of coming back about 30 percent. If you have eight dams to get past, and you are unfortunate to hit eight dams, you decrease your chances of returning by about 80 percent. That builds up and it stacks up.”

Earlier in the evening Jones stated that there is a clear difference in return rates for John Day River spring Chinook, which only face three mainstem Columbia dams – John Day, The Dalles and Bonneville – versus those from the Snake, which face eight – the aforementioned seven plus McNary.

He acknowledged that spilling water over the dams instead of running it through the turbines in spring has helped to a degree in flushing smolts downriver, but he and fellow panelist Jack Glass also shared stories of so-called “tech-no-fixes” – of convoluted juvenile fish bypass systems at dams, of smolts trucked down to Bonneville and released into water so warm they were jumping out of the river in thermal shock, as well as making easy, fast meals for predatory birds.

Glass did allow that the Snake dams were being managed to make fish passage easier and he was more careful with his words around what would happen with the structures, broaching breaching, which would leave portions in place for the river to flow around.

He said that he and his son – they’re both full-time fishing guides – depend on good salmon runs, calling them the “bloodline of the Northwest.”

Chris Hager, executive director at the Association of Northwest Steelheaders, said today’s fast-filling fishery quotas stand in “stark contrast to what it could be, and the Snake River dams play a big role in that.” Lower Columbia Chinook seasons are managed around impacts on Endangered Species Act-listed Idaho-bound kings.

IF IT WAS JONES’ JOB TO TALK SCIENCE AND STATS during the restoration panel discussion, it was Liz Hamilton’s to get folks pointed in the right direction.

“Together we are a mighty force for conservation,” said the Northwest Sportfishing Industry Association’s executive director. “The sportfishing business community and our customers, though, are pretty conservative by nature, but maybe that’s why so many of us embrace the efforts to restore the lower Snake River basin if we can build a comprehensive solution that supports others who also rely on the river.”

“Because it’s cost-effective, and it will double and sometimes triple the smolt-to-adult returns in the river, double, sometimes triple the number of hatchery and wild spring Chinook and B-run steelhead back to the basin if we can build this comprehensive solution. And it will also benefit other stocks that migrate through the hydropower system corridor,” she said.

Last year federal operators decided to keep the four dams in place, despite having also recognized that removing them is the most effective way to restore runs. That drew a rebuke from Elliott Moffett of Nimiipuu Protecting the Environment, who said, “The status quo has not and will not work” and that “major changes need to occur in order to restore the salmon runs within the Nez Perce Territory,” where the Nimiipuu, or Nez Perce Tribe, live.

Hamilton spoke to that status-quo political thinking that has prevented forward movement on the issue.

“I think we’re done with those false choices, right,” she said. “We’re done with the us versus them. We’re done with the fish versus irrigation, fish versus energy. We can modernize this system in a way that creates irrigation and solutions for farmers. We can replace the power from the Snake dams with clean and renewable energy and, hey, how about conservation? We can upgrade rail, road and port transportation, revitalize waterfronts, and also include money for dam removal.”

“To engage in this mighty lift, we need the voices of these 400,000 anglers that fish in the river and who care about the future that we leave for our children and our grandchildren,” she continued. “So we have to be ready to put our differences aside and work together and we need to seek a Congressional action and a comprehensive legislative infrastructure package that protects and creates jobs and restores salmon and steelhead.”

“This is our moment and we need to grab it,” Hamilton exorted.

So what’s changed, making this the “moment”?

Regional leaders – from US senators to one of Idaho’s Congressmen to the four Northwest governors and others – are “leaning in and are asking those, ‘What if’ questions,” she said.

Questions like, how do we get past standoffs and roadblocks; how do we upgrade the system, create jobs, and ensure that salmon share in the prosperity?

Then there is the plight of the southern resident killer whales, bringing the problem of low salmon runs home to the residents of Pugetropolis in a way that arguments over far-off dams on a stilled inland river never could.

“What’s new is, this region is ready for this future,” said Hamilton. “But as important as all of this is – because the science didn’t drive anything and the salmon crisis didn’t drive anything – right now, the Pacific Northwest has the most senior and the most powerful senators and representatives that serve on committees that have influence over salmon and influence over infrastructure.”

Last week, Washington Senator Maria Cantwell (D), the incoming chair of the powerful Commerce Committee, held a hearing with Rhode Island Governor Gina Raimondo, who is President Biden’s pick to head up the bureau that oversees the National Marine Fisheries Service.

Cantwell stressed the importance of salmon habitat, restoration and stock assessments to Raimondo, who indicated she looked forward to working on the issues with the Senate committee.

Meanwhile, that Idaho representative, Rep. Mike Simpson (R), is said this week to be talking behind the scenes about “a $32 billion to $34 billion plan to breach the four lower Snake River dams, and replace the 1,000 aMW of lost power generation with clean energy resources and new transmission lines,” reported Clearing Up, part of NewsData, which covers Northwest energy issues.

The proposal from Simpson, a member of the House Appropriations Committee and the ranking Republican on the Energy and Water Development, and Related Agencies Subcommittee, “would also compensate irrigators, farmers, barge operators, electric customers and towns that rely on the dams, including Lewiston, Idaho, and Clarkston and the Tri-Cities in Washington,” it was reported.

“And so this is a magic moment right now where all these things are aligning,” NSIA’s Hamilton said. “Energy prices are dropping, people are tired of false choices – they want solutions. Covid has created the need for stimulus packages and jobs. So that’s why, gain, your 400,000 voices are so important, because united, this is a powerful conservation point at a powerful moment in history. This is our once-in-a-lifetime chance to make a truly meaningful difference.”

Host Betsy Emery of Northwest Steelheaders said that anglers need to let legislators know “this is something we want to happen. That is where your voice matters.”

I HAVEN’T FOCUSED ON OR WRITTEN NEARLY AS MUCH as I should have about the four lower Snake dams. There’s just all the other stuff that my job as high overlord of the word for four consumer magazines (read: chief proofreeder) entails and the sheer volume of fish and wildlife stories also competing to be told. Every week brings more ideas from readers and sources.

I do have strong ties to this part of the Northwest and I care about it. I went to Wazzu for a couple years or so, following high school buddies, and the river and its tribs and fisheries did not go unnoticed by us “Coasties.”

One of our roommates came from a Palouse farming family and we hunted those lands. He’s semi-retired now, the lucky dog, and we caught up last fall, talking about the dams and their future, resurgent Idaho B-run returns and the need to guard against shifting baselines, deer hunting and thinking about deer hunting, and his harvest-time job on the farm – driving crops to a processing plant near Moses Lake.

He told me about a car that had pulled out of the airport cutoff onto Highway 26 and nearly ended up as his big rig’s new cow catcher.

I know I don’t have the answers, but I am really intrigued by this new comprehensive effort on the Snake River dams.

I like what I’m hearing from Buzz Ramsey, about looking out for and working with those who would be impacted by the removals; about the prospect of improving access to inland habitat and restoring river to a more natural environment; from Tucker Jones and Liz Hamilton about reducing smolt mortality and increasing adult returns; and the alignment of will towards accomplishing it all.

Those are all key buy-ins for me, making it seem more doable, or at least raising the conversation to the next level in what in all likelihood will be a very long talk. And it will, if Elwha and Klamath removals are any indication.

It’s a tall order, but those are relatively low dams on the Snake and I fear that time is short for the fish, so I can see stepping on the gas.