Washington Wolf Numbers Jump Nearly 25%

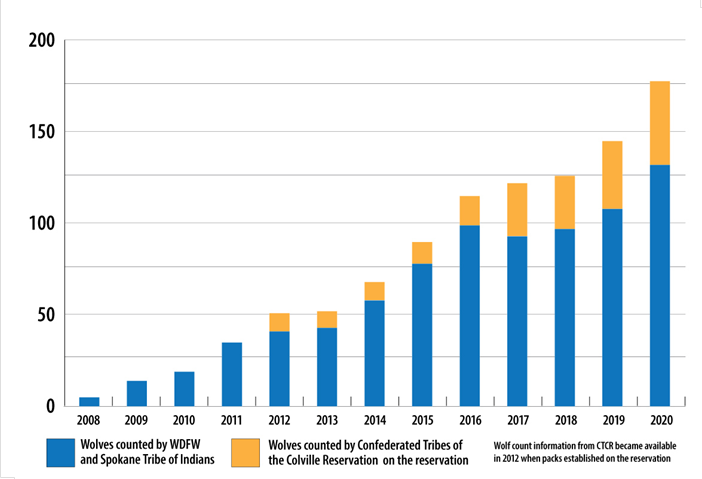

Washington’s wolf population rose once again – and sharply this past year – and now number a minimum of 178 as of this past winter count, up from 145 at the end of 2019, according to WDFW.

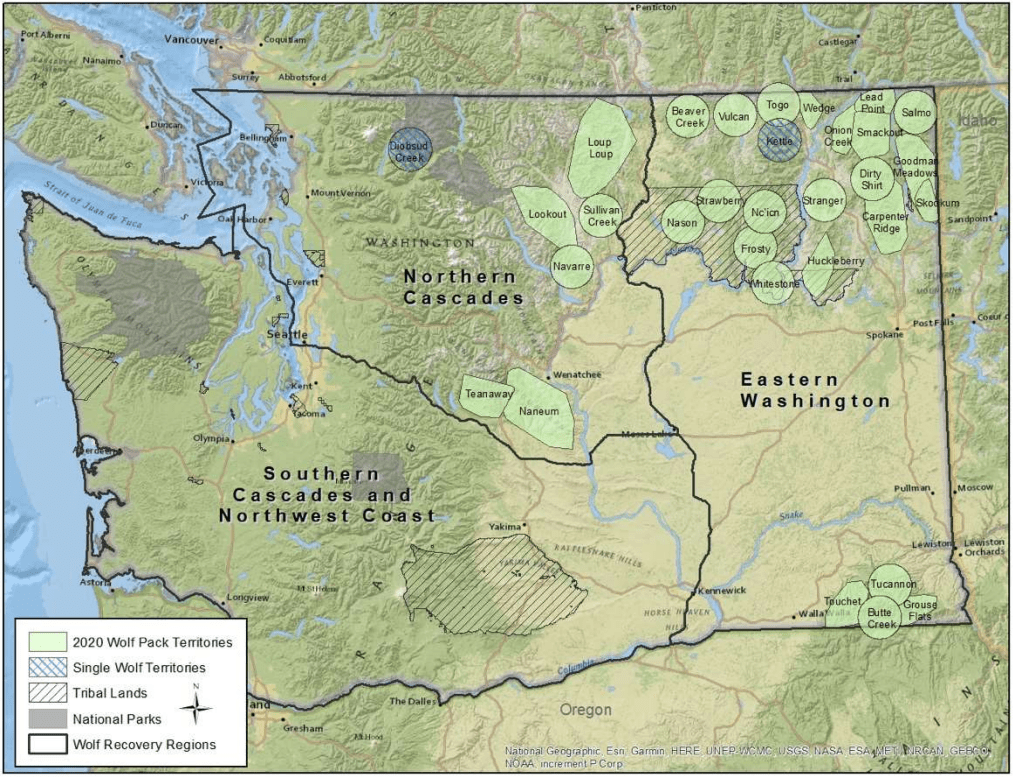

The agency, which released its annual report this morning during a meeting of the Fish and Wildlife Commission, also said there were at least 29 packs across the state, of which at least 13 were successful breeding pairs.

The figures include 132 wolves and 24 packs on WDFW-managed areas and 46 wolves and five packs on the Colville Reservation, though there is less certainty on the latter two figures because tribal managers consider the species recovered and rely on incidental reports, state managers intone.

The 2019 numbers were 108 wolves and 21 packs, and 37 wolves and five packs, and 10 breeding pairs.

“We’re still on a good upward trend,” Ben Maletzke, statewide wolf specialist, told commissioners.

Maletzke also noted that for the first time the North Cascades Recovery zone met its breeding pack recovery goal – four. It was the site of the state’s first pack in modern times, the Lookouts, which were confirmed in 2008.

However, no packs let alone wolves are known to occur in the South Cascades/Olympic Peninsula region, the third of the state’s three recovery zones, and most of Washington’s population is still in the northeast corner, meaning required initial benchmarks to begin state downlisting are likely still years away.

“We are working on a periodic status review currently, which could change the parameters for being able to consider wolves ‘recovered,’ leading to delisting more quickly,” WDFW said in response to a question on Facebook.

At one time, WDFW felt that could be reached as early as 2021.

“I’m looking at these numbers and they look great, but they’re not south and they’re not west,” said Commissioner Jim Anderson of Buckley, a lifelong hunter.

In his comment he essentially identified the rub of getting to any sort of wolf season in Washington in the near term.

Commissioner Fred Koontz of Duvall touched on another – the direction wolf management is headed in Idaho, Montana and Wisconsin via punitive legislation, a troubling development for the Evergreen State given its differing political geography.

While gray wolves were federally delisted in the Northern Rockies in the early 2010s, it wasn’t until earlier this year that they were finally fully removed from Endangered Species Act coverage across Washington, though state protections remain.

In an echo of Anderson, Commissioner Kim Thorburn of Spokane wondered why Washington wolves tend to disperse north and east. Last year a male from the Lookout Pack went 480 miles north to 100 Mile House in central British Columbia and past years have seen numerous wolves from Central Washington also head into Canada, while one from the northeast corner ended up in Wyoming.

The state wolf plan includes translocation as a tool for moving nontroublesome wolves around inside Washington, but it hasn’t been used.

2020’s growth does reflect the 12th straight year of population gains for the apex predators and comes despite three wolves being removed by WDFW in response to livestock depredations, the legal harvest of eight by tribal hunters – six on the South Half of the Colville Reservation and two on the so-called North Half that is jointly managed by the state and Colville Tribes – the justified shooting of one for human safety, the roadkill death of another, two from natural causes and one from unknown causes.

WDFW reports four new packs – Navarre in Okanogan County north of Chelan in the southern Sawtooths; Vulcan in northern Ferry County; Onion Creek in northern Stevens County; and Skookum II in Pend Oreille County near the Idaho line.

The agency readily admits that the annual count is a minimum. It also comes at a low point in the population cycle of wolves, which crests each spring and summer with the year’s litters, then declines as starvation, disease and other factors take their toll. It’s also easier to count packs in winter and to that end, 12 wolves from eight packs were captured in 2020 for radio collaring and through the year 21 wolves in 14 packs were monitored.

All in all, the news is positive for wolf fans, but they will have heartburn after Vice Chair Barbara Baker of Olympia used language similar to something Director Kelly Susewind said a month ago or so and drew blowback.

“We’re going into wolf season and I’m sure we’ll hear more from you in the coming months,” she said to Maletzke and Dan Brinson, WDFW Conflict Section manager.

Even as 76 percent of the state’s packs stayed out of trouble with livestock last year, 24 percent, or seven packs, proved problematic.

There were nine confirmed cattle deaths and 30 confirmed injuries to cows, plus one herding dog, with another five calves probably killed or injured by packs.

WDFW reported it spent $1,554,292 on wolf management in 2020, a figure that includes $110,035 to 33 livestock producers who enrolled in Damage Prevention Cooperative Agreements and covered nonlethal tactics like range riding and anti-wolf lighting and fencing, $150,640 for contracted range riders, $77,281 for lethal removals and $1.2 million for management and research.

“Funds came from additional fees for personalized license plates (34%), endangered species license plates (5%), state general fund apportionments (25%), federal contracts (14%), unrestricted state wildlife funds (14%), wildlife compensation for livestock damage funds (7%), and wolf livestock conflict funds (<1%),” the annual report states.

Part of that wolf research is the Washington Predator-Prey Project in Okanogan and Stevens Counties, a legislatively mandated effort to figure out the impacts of wolves and cougars on deer, elk and moose – as well as each other. So far 230 whitetails, 137 mule deer, 93 elk, 34 cougars and several wolves have been captured and collared for the study, which is in year five of five, with results expected to begin being published next year.

WDFW put out a video about that work earlier this year, and last year debuted another on how it counts wolves and the death of the “patriarch” of a Central Washington pack, the highly incestuous 32M and an object lesson into what has effectively been until recently a dead end in Washington’s wolf world.

With the 178 known wolves and 29 packs in Washington and 173 in 22 reported in Oregon earlier this week, that means there were at least 351 individuals and 55 packs in both states as of the end of last year, the most on record.