2022 Northwest Fish And Wildlife Year In Review

As another year winds down, I’m again taking a look back at important, notable and unusual stories in the Northwest’s fish and wildlife world.

From a record sockeye run, state record catches and record bull elk to commission controversies, Congressional craziness and the dam removal front, from cougars with a taste for wolves and selfish shellfish swine to a very wayward moose, wandering walleye and a guy who caught a salmon with his kiteboard, 2022 was a helluva ride. Here are some of the fish and wildlife stories I found myself writing up or following closely over the year that just was:

JANUARY

The Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission found itself in the thick of a storm at the start of the year, as state lawmakers mulled bills to remove and appoint members; stuff the citizen panel and its charge, WDFW, under the elected state lands chief; and create a task force to come up with new WDFW governance options, study tweaking or ditching the commission, and review both bodies’ statutory mandates. None of the bills did much of much except attempt to promote a sense of dysfunction – will we see similar ones when lawmakers meet in early January 2023?

While I could probably find something related to Washington’s spring black bear hunt for every month of the year, things came to a rapid boil right out of the gate when the even-more-short-handed commission (one member resigned in December 2021) voted 4-3 to accept hunters’ petition to reinitiate rulemaking for a 2022 season and then, three days later, three new members were appointed by Governor Inslee, essentially insuring it would only be a temporary victory for advocates of the limited-entry hunt with less than 700 tags, a 20 percent success rate and a stable bruin population base, and indeed the result was soon reversed.

Inslee’s appointments shifting the commission from its traditional base of support to a more preservationist take also drew fire from the Washington Chapter of Backcountry Hunters and Anglers and the Inland Northwest Wildlife Council, who stated it appeared that, once again, key sporting stakeholder groups had not been consulted before the new trio was named. And in response to claims the commission was “dysfunctional,” member Kim Thorburn pointed right back at that appointment process. The former chair, Larry Carpenter, had served for over 451 days without an official reappointment from the Governor’s Office, while a vacant Eastern Washington seat went unfilled for 390 days. “We don’t need new laws to improve the functioning of the Commission but instead, we need elected officials to follow current law,” the Spokane birder and hunting and fishing supporter wrote.

In Idaho, the Department of Fish and Game published results of a two-year study on steelhead. It was found that, when it comes to this popular far inland fishery, wild steelhead are caught less often than hatchery ones, and they survive “at a very high rate after being caught and released … good news for anglers because wild steelhead survival is critical to continuing fishing seasons and ensuring they are protected while anglers target hatchery fish.”

Robert Lackey, a longtime professor at Oregon State University’s Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, posted a sober video about why Northwest wild salmon and steelhead stocks have collapsed and the very, very, very long odds that they’ll ever recover. He essentially argued, given longterm declines driven by 200 years of altering absolutely everything as matters of accepted public policies, an expected tripling of the region’s population by the end of this century and the low likelihood that we residents can – or even want to – collectively change our ways in major ways that benefit fish and habitat, we salmon advocates might as well make due with the new fish species moving in as well as rename one of them, American shad, as American salmon and “declare victory.” That was tongue in cheek, but the rest of his argument made the rounds in serious Northwest sportfishing leader circles.

FEBRUARY

The seesaw over gray wolves never ends. On February 10, US District Court judge in Northern California vacated 2020’s federal delisting in the western two-thirds of Washington, Oregon and elsewhere in the Lower 48 outside of the Northern Rockies, taking away full WDFW and ODFW management of the species after a scant 13 months of being in charge.

Washington fishing managers have sent out literally thousands of rule change notices over the past couple decades, but it was a rare moment when agency hunting honchoes fired out one – to allow electronic calls for snow geese after “exceptionally high productivity” on the Arctic island the birds breed on translated to “record-high” flocks in parts of Northwest Washington and the Columbia Basin, which led to crop damage and other concerns. The electronic devices, like battery-powered decoys, are otherwise banned, but the call exception was to help hunters create a “cone of sound” to draw birds in and harvest more.

WDFW and Puget Sound tribes sent the National Marine Fisheries Service a new 10-year Puget Sound Chinook Harvest Management Plan to review. If approved, it would provide longer-term ESA coverage versus the annual review of fishing plan that’s been done since the previous plan expired in 2014, though given the expected 15- to 18-month-long process it may not be in place for 2023’s North of Falcon salmon season setting shindig.

Bills in Congress to allow the Siletz and Grand Ronde Tribes to renegotiate fishing, hunting, trapping and gathering rights agreed to in raw 1980s’ deals with the state of Oregon, as well as manage those resources, were considered at a US Senate meeting. The move came as ODFW negotiated new similarly themed MOAs with other tribes such as the Coquilles and Cow Creek Band of the Umpquas.

In the midst of a long dry spell in midwinter, WDFW managers began to worry about coastal steelhead returns. Based on early indications from state creel checkers and tribal fishery managers, Willapa Bay and Forks-area runs looked like they were coming in “well below forecast – not just a little bit, but significantly,” leading to an early shutdown a week later. Ultimately, more fish than predicted actually returned, though escapement goals were still not met on five systems.

MARCH

Midwinter’s drought came to a halt and, inevitably, led to the loss of 3.5 million young chum salmon at a Hood Canal hatchery inundated by flood waters. The facility is being used to increase chum production for southern resident killer whale diet needs and provide feedstock for sport and tribal fisheries. In the end WDFW said it would be able to backfill 70 percent of the lost fish.

WDFW hasn’t been as aggressive on the land-buying front in recent years, but in March the Fish and Wildlife Commission signed off on three major deals, acquiring 1,513 acres in far northern Douglas County to secure habitat for mule deer, sharptail grouse, pygmy rabbits and other shrub-steppe critters; 1,035 acres south of Olympia and just to the west of Tenino for the stunning new Violet Prairie Unit of the Scatter Creek Wildlife Area; and 94 acres on Willapa Bay between Baycenter and Naselle and smack in the middle of the 6 1/2-mile-long clam- and oyster-rich Nemah Tidelands.

Some $220 million from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law was earmarked for adult fish passage over a dam on the upper Green River east of Seattle, as well as flood management and increasing water supplies on the system, and hundreds of millions more in a defense bill at the end of the year were set aside to provide for juvenile fish passage downstream. It effectively will reopen 100 stream miles worth of habitat that have been blocked by the 1962 dam and a previous plug built in 1913, benefitting Chinook, coho and winter and summer steelhead, as well as the fishermen and natural systems that depend on them. Meanwhile, there was cautious optimism on the North Fork Lewis system after PacifiCorp appeared ready to add long-promised fish passage facilities on its three reservoirs there, news that state and tribal fishery managers and conservation groups viewed as a potential “significant step toward restoring access to critical salmon habitat” on the system.

Hunter education in Oregon celebrated its 60th anniversary in late March. Originally voluntary, the program became mandatory for those hunters 17 and younger in 1962, and according to ODFW it has led to a sharp reduction in the number of unsafe incidents and fatalities during the various hunting seasons. “Injuries per participant from hunting are actually much lower than other common forms of recreation like football,” ODFW stated in a Facebook post honoring the program.

APRIL

While federal and state officials want to significantly boost wind and green energy development in the coming years and decades, proposals to do that off the Northwest Coast ran into turbulence after a Mercer Island company submitted an unsolicited proposal for a 2,000-megawatt wind farm several dozen miles off Westport and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, or BOEM, identified a pair of “call areas” off Gold Beach and Charleston. Worries include how the floating windmills will impact fisheries as well as ocean upwellings and what that will do to the marine foodchain.

Former Washington Fish and Wildlife Commissioner Fred Koontz called on state residents to “rethink” WDFW’s purpose and encouraged lawmakers to change the agency’s mandate in a Seattle Times op-ed. The mandate boils down to “preserving, protecting, and perpetuating the state’s fish, wildlife, and ecosystems while providing sustainable fish and wildlife recreational and commercial opportunities,” but Koontz argued it should “direct the department and commission to recognize that ensuring wildlife’s long-term diversity, health, resiliency and sustainability as a public wildlife trust is its existential purpose. Resource extraction of a subset of diversity must be secondary” – words that would spark interest among current commissioners.

Both states’ wolf populations continued their inexorable growth, with Washington’s minimum count topping 200 for the first time, according to WDFW’s 2021 year-end report, and Oregon’s tally at least 175. Where the former state’s packs continue to pack into the northeast corner, the latter’s are spreading out more, but a pair of wolves was reported hanging out together in Klickitat and Yakima Counties, a first for that part of the Evergreen State.

After hours upon hours of testimony on Rock Creek Hatchery summer steelhead production, the Oregon Fish and Wildlife Commission went nuclear, voting 4-3 to eliminate the North Umpqua program, a bitter decision given that ODFW staffers found the fish had no effect on wild steelhead numbers. The agency had instead proposed reducing releases from 78,000 to 30,000 and improving the facilities infrastructure to address pHOS issues. County officials, derby organizers and a local fishing guide fought back, filing papers for an expedited court review, and a county judge granted them an injunction and ordered the release of some 75,000 smolts. In the end the fish were smaller than usual because of power issues at the hatchery where they were initially raised.

A $1.1 billion verdict against the state of Oregon over more wholistic management of state forests instead of maximizing logging and payments to counties was overturned by an appeals court and subsequently upheld by the state supreme court. The Oregonian termed it “a major victory for the state” and reported it means the Department of Forestry has “the discretion to manage state forests for multiple uses including clean water, wildlife protection and recreation.”

MAY

An invasive European green crab was found in central Hood Canal, the first discovery in the fjord and the furthest south in Washington’s inland seas the species has been found so far. By the end of November, a record-breaking 269,000 of the unwanted crustaceans had been removed from state waters, mostly in the North Sound, North Coast and Willapa Bay, as new funding allowed state, tribal and other entities to massively expand their eradication efforts. The worry is that green crabs could alter native ecosystems.

Inseason updates showing 57,000 more spring Chinook returning than originally predicted allowed Columbia salmon managers to reopen the lower river’s fishery essentially from May 12 straight through to June 16, the beginning of the summer king management period, which itself was expanded from a mere seven days to that plus nearly half of July. It was all among the signs that the ocean had become more productive for Northwest salmon stocks.

Harney County resident Chris Lardy was taken directly into custody to serve a judge’s surprise six-day jail sentence after Lardy had reached a deal with prosecutors over exceeding the bag limit on elk and unlawfully killing a bull during a closed season. The disgusting incident occurred in Southeast Oregon last December and involved the firing of “17 to 30-plus rounds” into an elk herd after first pursuing them in a vehicle, killing seven and leaving all but two to waste. Lardy lost his hunting privileges for two years and was ordered to pay $2,000 in restitution to ODFW, among other sentencing provisions.

JUNE

Washington State University researchers confirmed the link between abnormal or asymmetrical antlers on elk with debilitating hoof disease after looking at hunter harvest reports for roughly 1,700 bulls. They found that two-thirds of elk with six points on at least one antler “had asymmetrical antlers when hoof abnormalities were present.” It’s well known that elk or deer with an injured foot will typically have an abnormal antler on the opposite side, but this study shows that transmissible treponeme‐associated hoof disease “is having a an impact at a population level.”

Boggan’s Oasis, the famed waystation on the Grande Ronde River that burned down in November 2017 and was rebuilt and reopened the following year, changed hands in June as Bill and Farrel Vail deservedly retired to Clarkston after decades of serving up burgers and shakes to hungry fishermen, travelers and locals, and Louis and Tia Villagomez, formerly of Pierce County, took over. At last check, fishing “has been great. And the fish are NOT LITTLE.”

The Recovering America’s Wildlife Act – cheered by hunting and other traditional conservation organizations as “landmark legislation,” “unprecedented,” and the “most significant wildlife conservation bill in half (a) century” and which would have provided millions of dollars annually to individual state and tribal managers for imperiled wildlife – passed the US House but stalled late in the year in the Senate when it wasn’t included in the omnibus spending package.

Two more northern pike were netted out of Lake Washington while shad numbers nearly doubled over 2021’s catch during the now-annual spring netting, worrisome trends for the big Seattle watershed. Concerns center around the nonnative species gaining a foothold and further reducing the survival of native fish populations such as salmon that support state and tribal fisheries and are regionally economically, culturally and environmentally important. The idea the test netting could lead to a commercial fishery for warmwater species suffered a bit of a blow with new health recommendations released late in the year not to eat any Lake Washington largemouth or smallmouth and to limit meals of yellow perch due to high perfluorooctane sulfonate, or PFOS, levels.

When a Georgia Congressman introduced a bill to scrap a highly regarded excise tax on guns and ammo that has provided $15 billion in federal funding for wildlife conservation and hunting over eight and a half decades, it was laughable but its willful partisanship also garnered an eyebrow-raising amount of support in the country’s capital, 57 fellow Republicans. That figure shrank after pushback over the attack on the Pittman-Robertson Act, and as of the end of the year the bill had gone nowhere in the House, which is slated to change from Democrat to Republican control in the new year.

Rod builder Tom Posey, CEO of Lamiglas of Woodland, Washington, died when the plane he was flying crashed at Vancouver’s airfield. The fish and fisheries advocate was 64 and had built up the company his father Dick founded and ran until his 2015 passage. “Give it your all.” RIP

JULY

Washington’s spring bear hunt saga continued with the Fish and Wildlife Commission voting 5-4 to tell WDFW wildlife managers not to bother preparing a proposal for a 2023 season because members wanted to set a spring bear hunting policy first. Fast forwarding to the inevitable, in mid-November the panel again voted 5-4 that it “does not approve recreational hunting of black bears in the spring,” ending the season as it has been known. Commissioners say WDFW can still bring them proposals for management hunts – kinda like they had been doing with mitigating elk calf and deer fawn predation, timber damage, human conflict and providing a big game hunting opportunity in spring – to shoot down.

A survey performed every four years or so found that support for hunting remains strong in Washington and opposition to the traditional activity barely registers more than single digits, with 75 percent of state residents strongly (44 percent) or moderately approve of legal, regulated hunting, while 10 percent moderately or strongly (5 percent) disapprove. That said, there was a dropoff from the 88 percent support for hunting found in 2014 (and 82 percent in two previous surveys), though notably there was not a corresponding rise in opposition. Another occasional survey, this one of hunters, found WDFW’s management of deer “was not rated very well,” with two-thirds of deer hunters putting it in the “bottom half of the scale (35 percent fair; 28 percent poor)” and one-third in the top half (6 percent excellent, 25 percent good). Twenty-six percent of deer hunters called predators the most important issue facing the state’s deer herds, while 30 percent of elk hunters said the furry fangers were theirs, topping habitat and disease concerns, respectively.

The first of two 2022 court defeats for Fish Northwest occurred in July as the Anacortes-based fishing organization’s lawsuit challenging authorization of recent Puget Sound Chinook seasons was shot down by one federal US District judge in Seattle. That was followed in October as another arbiter declined to allow FNW to intervene in the Boldt Decision on behalf of state anglers.

At a time of changing theories in fish and wildlife management and conservation and the funding thereof, Ruth Musgrave replaced JT Austin as Washington Governor Jay Inslee’s senior natural resource policy advisor. Musgrave’s background is in reforming fish and wildlife agencies; she replaced JT Austin.

AUGUST

Claiming that Olympic Peninsula summer-run steelhead are “nearly extinct” and its winter-run stock is “declining and losing its life history diversity,” the Wild Fish Conservancy and The Conservation Angler petitioned NMFS on August 1 to list the prized fish as either threatened or endangered, starting an initial 90-day (give or take) review period for whether a federal ESA listing may be warranted, which would spur deeper and deeper looks. In a mid-December statement to this reporter, federal spokesman Michael Milstein in Portland said the petition review was “still moving through the process, I think probably a few weeks away now.”

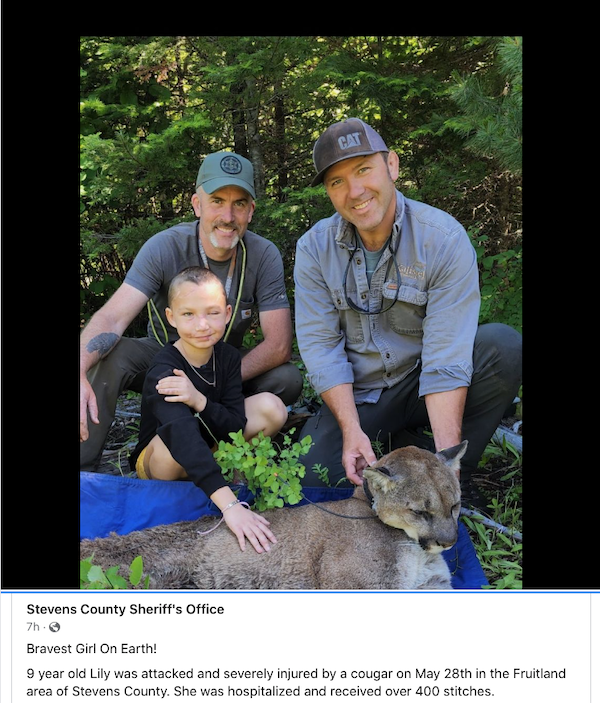

In the first of two Washington black bear attacks this year, a Whatcom County jogger suffered “multiple injuries to his hands and feet” after encountering a sow with cubs in a forested area. It was the first bear attack in the state since 2015, but in late October a woman who’d let her dog out from her house next to a riverside park in downtown Leavenworth was charged by a sow and sustained injuries that required a trip to the hospital. Both offending bears were lethally removed, with the latter female’s cubs taken to a wildlife rehab facility.

Federal scientists found that Chinook and steelhead are also affected by tire preservatives that react with ozone and get washed into streams by storms, though not to the same extent as coho – up to 13 percent of kings and 42 percent of steelhead die, compared to 92 to 100 percent of silvers. There was a sliver of good news in that, like chums, sockeye aren’t affected, but findings out later in the year were very sobering: “6PPD-q has been polluting and killing salmon and steelhead for decades, long before we even knew the compound existed” and figured out that simple rain gardens can help filter out the toxins, though whether that can be applied on an industrial scale is another question.

It was an active year on the lower Snake dams removal front, with anglers urged to get behind the effort, rallies held around the region in support of it, federal assessments finding that breaching is “essential” to rebuilding the river’s salmon and steelhead stocks and that there’s an “increased level of concern” around Snake spring/summer kings, and the feds, Oregon, tribes and others part of a long-running lawsuit over Columbia system hydropower operations agreeing to another stay of litigation so they can continue working toward a long-term solution. But the biggest news might have been Washington US Senator Patty Murray’s and Governor Jay Inslee’s long-awaited report that said before Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose and Lower Granite are sundered, their services and benefits – electricity generation, barging, etc. – must be replaced or mitigated for.

Crews pulled 1,800 creosoted pilings from the site of an old dock in the Duwamish-Green River estuary, on the edge of Elliott Bay, as part of an $8.1 million project to improve the system for salmon, steelhead, other wildlife and local residents. It added to the 14,461 pulled by DNR around Puget Sound and 100 WDFW took out of the old Point No Point resort.

Don’t tell certain members of Washington’s Fish and Wildlife Commission who don’t think WDFW should be promoting hunting, but the agency and partners at First Hunt Foundation, INWC and the Kalispel Tribe, among others, teamed up to host a great mentored opportunity for new hunters to learn about hunting, ethics and processing meat before they turned their attention to a damage control hunt for whitetail on private farmlands in the state’s northeast corner, with eight of 12 participants harvesting their first deer!

After 2021’s horrible summer steelhead return of just 630, good signs began to emerge on the North Umpqua, with improved numbers of both hatchery and wild fish. By the end of the year, the Winchester Dam estimate showed the most summer-runs coming back to the Oregon system since 2017, 3,866.

Bucking the trend of bad news around Northwest big game herds, the population of whitetail deer on islands and mainland areas of and along the Lower Columbia is doing good enough that WDFW recommended downlisting the subspecies from endangered to threatened. The herd has grown from just 545 in 2002 to an estimated 1,296 this year, mostly thanks to a successful effort to translocate animals to the Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge. A decision on the new listing classification is expected in early 2023, as is an uplisting for rare Cascade red fox.

Wild coho retention opened in late August off Westport for the first time since 2015 as managers swapped a balance of 40,000 hatchery fish left in the quota for 14,000 unclipped or clipped silvers. In a similar move, Oregon’s September any-coho fishery quota was increased after an “impact-neutral” inseason trade, while at least nine coastal Beaver State rivers also hosted their second-fall-in-a-row fisheries following a period of low abundance.

Approximately 2 days, 11 hours and 31 minutes into an unexpected Marine Area 13 salmon fishing shutdown, WDFW reversed course and reopened these Deep South Sound waters for Chinook and coho. A chagrined agency manager who made the recommendation to close it said he’d been looking at anecdotal fishing reports and tribal netting results and admitted to “eating a lot of humble pie” as it soon became apparent enough kings were actually around to have kept angling open.

SEPTEMBER

Reacting to off-the-charts late August recreational catches at Buoy 10 that swamped preseason tule Chinook impact expectations by a very significant margin, state managers closed 144 miles of the Lower Columbia to salmon fishing, from the mouth up to Bonneville Dam. It was a tough blow that also served as a prelude to a topsy-turvy balancing act through the rest of the fall season as ODFW and WDFW reopened fishing in different portions of the big river to try and access abundant hatchery coho and upriver brights while also protecting ESA-listed wild tules, then shut down all Chinook retention from Buoy 10 to Tri-Cities when the URB forecast was downgraded. It all led to a lot of angler frustration and late in the year, state managers posted a survey as they consider “ways to reduce the likelihood of this outcome in the future.”

In a harbinger of new fishery management being increasingly applied to Puget Sound streams, the hatchery coho opener on the Cascade River was delayed so as to avoid going over state-allocated encounters on summer/fall Chinook in the Skagit Basin. While incidental Chinook catches haven’t been monitored in the past, starting last year they began to be; according to WDFW, doing so “helps guide management actions to stay within conservation goals while providing maximum opportunity.” Applied to the Stillaguamish this fall, the new paradigm kiboshed the vast bulk of the coho season because the prohibitively low number of king impacts had been met. (Angling was eventually reopened in late November, a time when damn few silvers would be still alive in the Stilly, let alone be worth catching.)

National wildlife refuge managers announced that starting next season, hunters will be able to pursue turkeys during the fall at Turnbull NWR near Spokane and Canada geese in September at Baskett Slough NWR west of Salem, two of more than 100 new opportunities OKed across the country. The three most recent presidential administrations, Democrat and Republican alike, have all made a point of increasing fishing and hunting access on federal lands.

Oregon bowhunter Kaden Titus arrowed the new state record archery elk, a monster Union County bull that scored 392 0/8, as measured by Northwest Big Game Inc., and over 23 points more than the previous high mark, putting Titus into a host of record books. Meanwhile, Hoquiam logger Brian Dhoogie bagged a veritable Irish elk in the form of a 648 4/8 bull he shot on a 10,000-acre Idaho ranch in early October. The hunt was a birthday present from his wife and while he didn’t brag his bull up at all, once pics hit social media, reaction poured in. Dhoogie’s bull won’t make it into record books honoring the taking of free-ranging bulls, but it could still qualify for Safari Club International’s “estate animals” category, not to mention make one hellllllllll of a wall mount and elk dinners.

Just as a very promising razor clam season with 56 fall/early winter dig days was set to begin on the Washington Coast, it was postponed as domoic acid levels began to trend up at three beaches and exceeded safe-to-eat levels on one. Prospects were not great to begin with on Oregon’s North Coast, but clamming there too was halted before it could really begin due to marine toxins. While WDFW was able to pull off limited digs in early to midfall, by early November the season was put on indefinite hold because of unsafe domoic acid levels, a blow to coastal economies that reap tens of millions of dollars during an otherwise slow time of year.

By late September, Western Washington’s driest summer on record, as well as one of its warmest, left a number of rivers running at all-time lows just as fall salmon began to return to them. In early October and with no real autumn rains in sight, federal and state managers concerned about low flows restricting fish movement and concentrating harvest issued sweeping sport angling closures that affected Olympic National Park and coastal streams. It wouldn’t be until late in the month that the rivers began to reopen, though in the case of the Queets, a significant Chinook overcatch by Quinault Indian Nation fishers in mid-October kept it closed.

OCTOBER

Some of WDFW’s fiercest courtroom and management opponents held what they billed as the “inaugural Washington Fish & Wildlife Management Reform Convention” on Vashon Island as groups like Wild Fish Conservancy, The Conservation Angler, Center For Biological Diversity, Humane Society of the United States and Washington Wildlife First, among others, organized around the theme of “transforming the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife into an agency that prioritizes conservation over consumption, emphasizes the intrinsic value of individual animals and healthy ecosystems, and represents the values of all the people of the state.” It was a surprisingly bold move, but after a little sunlight was applied to the gathering, organizers promptly disappeared the agenda and all other details.

At the same time, local, state and national hunting and fishing organizations banded together to form the Washington Fish and Wildlife Conservation Partnership, which describes itself as “dedicated to protecting the state’s hunting, fishing and trapping heritage through science-based fish and wildlife management.” Spurred by the cancellation of the spring bear hunt, the group aims to build a coalition that can “work together to protect the state’s outdoor heritage,” and one of its first actions was to send a letter to Governor Inslee in support of reupping Commissioner Thorburn’s appointment, though supporters earlier this week acknowledged it was unlikely she will be granted another term.

NOVEMBER

We don’t often get to talk about brand-new runs of salmon (and, ahem, I guess I forgot to mention this one in 2021’s year in review), but fish from year two of the late-timed Ringold Springs coho program began to return in bigger numbers in November. Jumpstarted with eggs taken from Lower Columbia silvers, state managers hope this run provides additional forage for southern resident killer whales as well as additional fishing opportunities below the Mid-Columbia facility and elsewhere. It’s really a December return, with three-quarters of 2022’s return so far showing up this month.

National Park Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service officials restarted a bid to restore and manage grizzlies in Washington’s North Cascades, with their draft plan’s preferred option being to release three to seven bears captured in interior British Columbia or the Northern Rockies annually for five to 10 years, upping that number once a population of 25 is reached, and an end goal of 200 grizzlies within 60 to 100 years. A previous effort that looked at bringing the big bears back to the region fizzled out in 2020, during the waning days of the Trump Administration, when the Department of Interior quit working on the project. Reinitiating the effort drew applause and disappointment. Meanwhile, the Colville Tribes continued reintroducing lynx onto their reservation in Northcentral/Northeast Washington, nine over last winter and 10 in midfall.

A Washington State Academy of Sciences report found that with harbor seal and sea lion predation in Puget Sound and the coast likely impacting salmon recovery, lethal removals should be tested to see if it helps fish survival. That of course would require an act of Congress to adjust the Marine Mammal Protection Act and while a big lift, it’s not impossible to change either, as seen with enhanced removals of both Californias and Stellers in the Columbia system. As reported in the Capital Press, scientists say, “The major risks of lethal removals appear largely social and political rather than risks to pinniped populations as a whole.”

With the odds low that Governor Inslee would reappoint him, Don McIsaac went out on his own terms, announcing he would resign from the Fish and Wildlife Commission at the end of the year when his tenure wraps up. It’s a potential loss for the consumptive community, given McIsaac’s solid support of hunting and fishing (true, commercial more so than sport fishing). Around 50 people would like to replace him, and some of the names will be known to the harvest community and some will raise eyebrows. Watch for announcements in the near term.

Grays Harbor system anglers’ hopes to fish for abundant late-returning hatchery winter steelhead were dashed when WDFW announced pending 2022-23 seasons, including yet another closure of the Skookumchuck – where some 3,800 clipped fish returned this past year and were mostly given away to food banks or put in local lakes – and the Wynoochee after the Quinault Nation communicated “extremely clearly” to state comanagers an intention to protect struggling wild steelhead runs in the watershed. It left state fishermen “kinda speechless,” though this year there was at least a chance to fish for late coho on some streams for a couple December weeks. While Willapa Bay and Forks rivers will be open for winter steelhead, the Queets won’t after WDFW and QIN couldn’t come to an agreement on it; the parties’ escapement goals for the river are quite different.

DECEMBER

In mid-December, members of Washington’s hunting/conservation world mourned the passage of Bobbie Thorniley, “co-founder of both the Hunters Heritage Council and Washingtonians for Wildlife Conservation,” per HHC’s Mark Pidgeon, who added that Thorniley “received both organizations highest honors … was a initial class inductee into the Hunters Heritage Council Hall of Fame … initial recipient of the Washingtonians for Wildlife Conservation Honorary Lifetime Member Award” and was an “original member of [WDFW’s] Game Management Advisory Council … I can’t list all the awards she received, there isn’t enough space on Facebook. Every award was richly deserved.” RIP

As a Deep South Sound creek saw a record outmigration of coho smolts this year thanks to dam removal and stream restoration work, the Lower Columbia’s “healthiest” wild coho run set a new high mark for a third year in a row at a PGE sorting facility for adult fish on the North Fork Clackamas, likely thanks to improved fish passage and “increasingly significant habitat improvements” benefitting instream rearing. Will there soon be an any-coho opportunity on the Clack and perhaps Willamette below the falls?

More collared Blue Mountains elk calves have survived to December than last year, but cougars are again taking the lion’s share among Southeast Washington’s burgeoning predator guild. WDFW Region 1 Manager Steve Pozzanghera said that of 73 device-wearing calves in this year’s research cohort, 48 had died, with 31 of 37 predator mortalities attributed to the big cats, while 23 calves were still “on the air as of earlier this month. At pretty much the same time in 2021, just 11 of 116 calves were still alive, sparking deep concern among harvesters, local producers and state wildlife managers because it was so far below the elk herd’s replacement needs, though infamously some fish and wildlife commissioners weren’t so worried.

Columbia salmon managers are forecasting a larger overall return of spring Chinook to the big river in 2023, some 307,800 hatchery and wild fish, and while it looks great for anglers on tributaries like the Willamette, Snake River expectations could put a damper on lower mainstem fishing. But the Columbia summer Chinook is up and fall king returns “should be similar” to 2022’s.

A federal judge in Seattle is recommending that part of a NMFS biological opinion governing Southeast Alaska commercial Chinook fishing go back to the agency for correction while also denying two anti-hatchery organizations’ bid to derail a prey increase program meant to help feed starving southern resident killer whales and which along the way will likely benefit Washington salmon anglers. Look for a final ruling early in 2023.

On New Year’s Eve, conservative Seattle radio show host Dori Monson who gave voice to fishing and hunting issues in the state’s biggest market passed away at home. He’d taken up fishing rather late in life with fellow broadcaster Tom Nelson of The Outdoor Line on 710 ESPN. RIP

Editor’s notes: For other takes on 2022’s outdoor news of note, please see Eli Francovich‘s coverage in the Spokane Spokesman-Review and Eric Barker‘s in the Lewiston Tribune.

For your further reading delirium, here are links to my previous years in review, including 2021, 2020, and 2018’s parts I, II and III, as well as the decade in review I did at the end of 2019. (Prior years were eaten by the internet, courtesy of some hackers.)

And if you’d like to help make the above rundown even longer, email me at awalgamott@media-inc.com with stories I spaced out on but are damned important too!

Correction: The original version of this mistakenly stated that Jeanne Moore, wife of Frank Moore, had passed away not long after his death in late January. That was based on the author’s faulty memory, which was incorrect. Jeanne is reported as alive. We regret the error.