‘Who Killed The Skookumchuck?’ Angler Asks After Drop

“Look at this. This is apocalyptic. There ain’t no steelhead getting up that. The hatchery’s up there, and this right here, I mean, it’s not even 2 inches deep.”

So stated Martin Hoeschen as he narrated a video he filmed along the dewatered Skookumchuck River immediately below TransAlta’s Skookumchuck Dam earlier this week.

On Monday morning it was like the drain plug had been pulled on the stream northeast of Centralia.

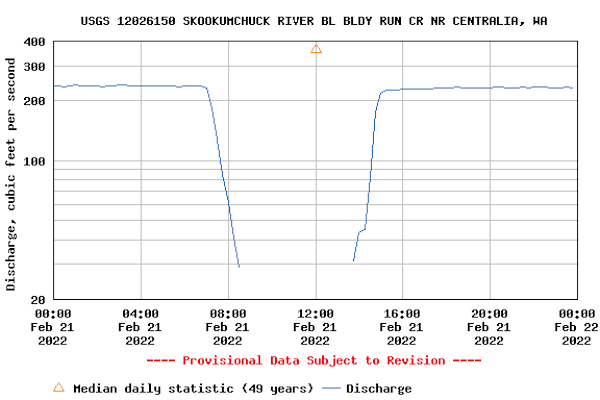

Water levels – which were already lower than usual for this time of year – suddenly and precipitously dropped from approximately 230-240 cubic feet per second to 30 cfs, and likely even lower. The U.S. Geological Survey gauge at Bloody Run, which is the first tributary below the dam, appears to have quit taking readings as flows dropped below 29 cfs.

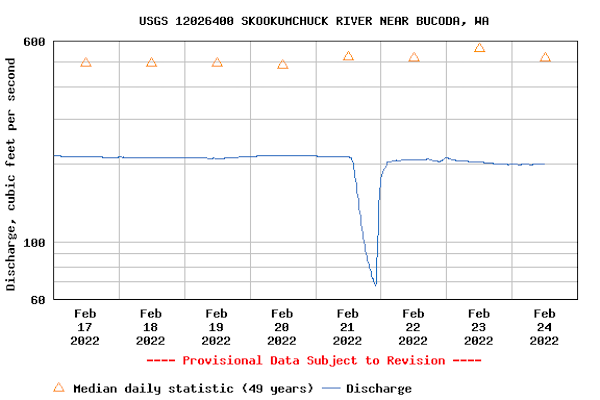

A downstream gauge on the Skookumchuck at Bucoda and even on the mainstem Chehalis as far down as Porter also recorded drops in flows.

Five hours later the river did rise back up and just as abruptly, but not before Hoeschen and his wife were able to tour the scene.

In several videos Hoeschen shot and shared with Northwest Sportsman, the lifelong Washington resident, bowhunter and local angler detailed how the sudden drop affected the Skookumchuck’s fishing spots like “The Corner Hole.”

“There’s still water, you know – I mean, it’s deep – but there’s no flow. The only flow is that,” he said while panning with his phone to a riffle. “That’s 3 inches deep. Not nearly enough for fish.”

In an email this morning Hoeschen described seeing trapped salmon and steelhead, potentially also exposing them to poachers.

“They could just wade through some of those stagnant pools and hand-scoop all the steelhead they could possibly want,” he said.

A still photo he also sent shows his wife as she walked their dog across high and dry gravel river bottom.

“That’s supposed to be underwater,” Hoeschen said of the scene. “There are pools in between there, and there’s adult fish swimming in them. Adult steelhead and coho salmon. And I absolutely am not – absolutely am not – whatsoever exaggerating. Not in anyway, shape or form.”

The Skook is home to one of Washington’s latest-timed coho runs, while now is roughly the peak of its hatchery steelhead returns.

It all left Hoeschen angry: “Who killed the Skookumchuck River?” he wants to know.

The timing couldn’t have been worse for the fish.

Just yesterday WDFW announced that sportfishing on all river systems draining to the coast would shut down March 1 due to very low returns so far of wild winter steelhead. Only one unclipped steelhead was reported so far at the trap on the Skookumchuck, which has been closed to angling since December 1 due to chronic poor returns across the Chehalis River basin in recent years.

“I’m wanting the perpetrators responsible for this to be accountable, regardless if it’s a ‘mistake’ or deliberately. Those involved need to be NAILED! This ridiculous, preposterous act of wanton disregard of our Washington state natural resources is indicative of how blatantly WDFW has been mismanaging everything,” Hoeschen stated.

WDFW certainly takes a lot of heat from all sides over fish management, but this case is actually wrapped around Skookumchuck Dam operators TransAlta.

TransAlta did not immediately respond to two requests to its media email hotline for comment, and questions have also been emailed to a supervisor at the dam. If they do respond, we’ll report their side in a followup story.

In the meanwhile, according to WDFW district fisheries biologist Mike Scharpf, the Canadian company was performing a “scheduled reduction of flows” on Monday for a “mandatory penstock inspection” at the dam.

A penstock is essentially the conduit for getting water from the body of the reservoir to point B – a turbine, sluice or other drainway.

In a February 10 email, Paul Hoebing, TransAlta’s Skookumchuck Hydro Supervisor, advised WDFW about the upcoming inspection, “which will require stopping flow through the dam which means the only flow into the river will be through our fish sluice and what’s coming through bloody run. We planned it for this time of year as we are usually spilling over the spillway but this has been an oddly dry February. The inspection will take up to 12 hours but most likely less. Will this be acceptable? Please advise.”

In a February 11 response, Peggy Miller, WDFW’s FERC, or Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, coordinator, thanked Hoebing for the heads up and stated, “Since it’s a mandatory inspection it has to be done,” but also asked him to “please consider slowly reducing outflow” and whether the inspection could be done instead when rain was in the forecast.

“Regardless, if flow during the inspection is close to current flow any impact to fish will likely be low. Gradually reducing flow will also help,” Miller wrote.

The day of her response, the Bloody Run gauge showed the Skookumchuck was running steadily between 241 and 255 cfs – but on the day of the inspection water levels dropped to just 13 percent of that mark, if not lower.

This Tuesday, Miller expressed surprise to Scharpf in an email about the drop.

“Wow, I didn’t expect flows to go below 30 cfs … Hope the gauge wasn’t reading right. Can’t remember if they have downramping criteria but he didn’t take my suggestion to slowly ramp down,” she stated to the biologist.

We couldn’t confirm a rumor that TransAlta had gotten a remotely operated vehicle stuck during their inspection.

In another email today provided by WDFW, Miller reported that TransAlta has a “minimum flow criteria” of 95 cfs as well as an “informal ramping rate standard,” though the latter was not included in the dam license as it was “likely overlooked” given the era it was approved.

She added that TransAlta had “never responded” to her February 11 questions about 1) how much water could flow through the dam’s fish sluice and 2) “what will be the approximate decrease (or increase) from current flow?”

It’s unclear if they are related to this week’s penstock inspection, but USGS data from the past two Februarys show blocky blips in river flows that are somewhat similar to Monday’s but nowhere near as deep. On February 12, 2021, Skookumchuck flows at Bloody Run below the dam dropped from 290 cfs to 245 cfs for a period of about four hours before rising again, while on February 21, 2020 they dropped from around 365 cfs to 339 cfs for several hours, then pulled back up.

Besides the dam, TransAlta also owns a nearby power plant. The dam is used to supply water to the facility, according to a company webpage, with some siphoned off to a WDFW salmon and steelhead hatchery below it.

Scharpf, the WDFW biologist, stated his agency worked with TransAlta “to make sure all production at the Skookumchuck hatchery would remain safe.”

But some fish in the river may have not been so lucky.

“Certainly WDFW is concerned about any impacts and have heard a few reports of some fish stranding,” Scharpf stated, adding. “Thankfully the duration of the drawdown was short.”

True, it was short, but it was also very deep.

Another biologist, this one outside state government, described the sudden dewatering as “absolutely devastating to juvenile Chinook.” The river is home to both spring and fall Chinook, and in late winter fry begin to emerge from the gravel and move to side channels and off-channel locations, which also are “the first places to get dewatered during a fast drawdown,” they said. Coho redds may have also been impacted.

This is the second time this winter that Washington dam operators have put fish in peril. A drawdown at Merwin Reservoir left some kokanee redds exposed.

TransAlta has tried to be good neighbors in the greater Centralia-Chehalis community as it pulls out of the coal-mining and coal-fired generation business here, donating land to a local development council for an industrial park and offering WDFW two-thirds of its 9,600-acre mine after cleanup for free if it bought the other third.

But the company also has questions to answer in the wake of one alert local angler’s observations.

Even as Hoeschen looks to get the word out on the incident, he fears those responsible may be “sweeping it under the rug, so to speak.”