Oregon Fishing Legend, Umpqua Protector Passes Away

Sad news from the Northwest fishing world: Frank Moore passed away yesterday.

Over nearly 99 years Moore lived a “storied life,” as Terry Otto wrote for a June 2014 feature in Northwest Sportsman that coincided with the 70th anniversary of D-Day.

“His accomplishments include helping to free France from the Nazis, starting the historic Steamboat Inn on the North Umpqua, entrance into the Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame, and protecting his beloved Umpqua River and its incredible summer steelhead from the ravages of logging,” Otto wrote.

In 2019, some 100,000 acres of public lands in the North Umpqua watershed were set aside as the Frank and Jeanne Moore Wild Steelhead Sanctuary.

Spokane angler Rick Itami recalled the first time he met this “war hero, savior of the North Umpqua, master fly angler and humble, kind and gentle soul.”

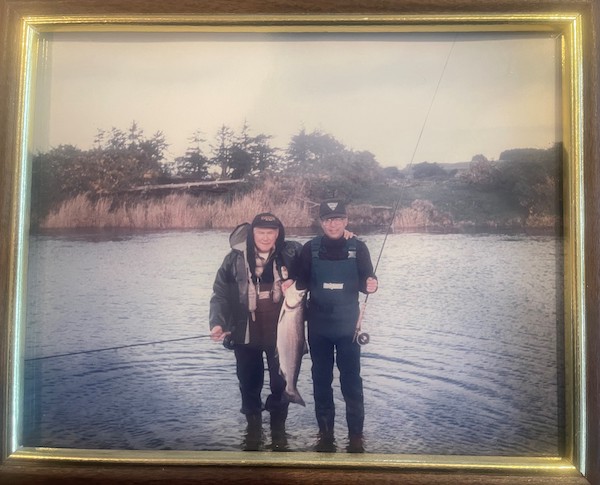

“I first met Frank in the 1990s on the Elk River on the Southern Oregon Coast, where he stood by me and coached me how to double-haul cast big heavy flies to fall Chinook. After a few clumsy attempts, I managed to get the fly out far enough for a good swing and hooked and landed my first salmon on a fly. Frank helped me beach the fish then gave me a big hug,” Itami said.

“He will be greatly missed,” added Itami.

Otto’s article detailed how, while serving in France in 1944, Moore saw salmon in a river there and returned 69 years later to fish in Normandy.

“We here in Oregon have to ask how we were lucky enough to be blessed with Moore, someone who we all owe a huge debt to,” wrote Otto. “We have the chance to honor him, and all the men who fought so hard with him, by following his advice: ‘Never stop dreaming, and never stop working to fulfill those dreams.'”

RIP, Mr. Moore.

Editor’s note: Here is Terry Otto’s 2014 story on Frank Moore in full:

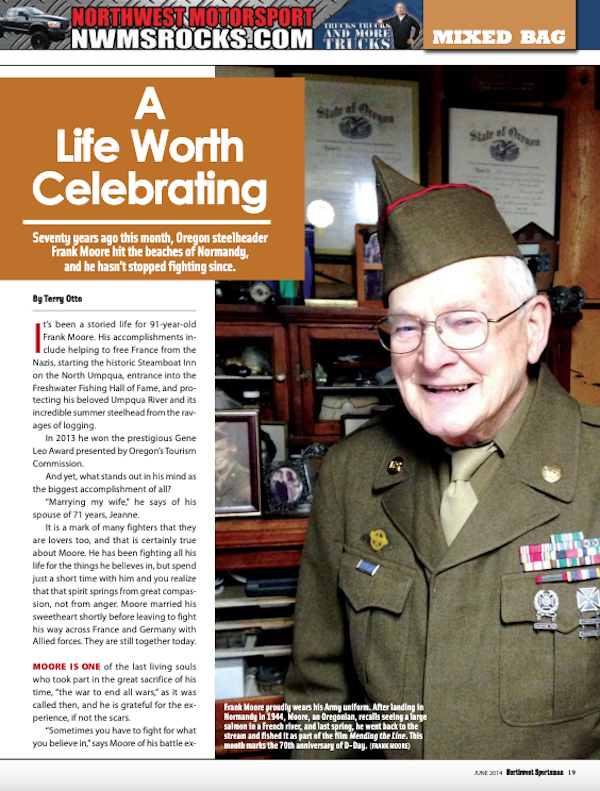

It’s been a storied life for 91-year-old Frank Moore. His accomplishments include helping to free France from the Nazis, starting the historic Steamboat Inn on the North Umpqua, entrance into the Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame, and protecting his beloved Umpqua River and its incredible summer steelhead from the ravages of logging.

In 2013 he won the prestigious Gene Leo Award presented by Oregon’s Tourism Commission.

And yet, what stands out in his mind as the biggest accomplishment of all?

“Marrying my wife,” he says of his spouse of 71 years, Jeanne.

It is a mark of many fighters that they are lovers too, and that is certainly true about Moore. He has been fighting all his life for the things he believes in, but spend just a short time with him and you realize that that spirit springs from great compassion, not from anger. Moore married his sweetheart shortly before leaving to fight his way across France and Germany with Allied forces. They are still together today.

MOORE IS ONE of the last living souls who took part in the great sacrifice of his time, “the war to end all wars,” as it was called then, and he is grateful for the experience, if not the scars.

“Sometimes you have to fight for what you believe in,” says Moore of his battle experiences. “I wouldn’t wish that on anyone, but it made me more of a leader than I would have been otherwise.”

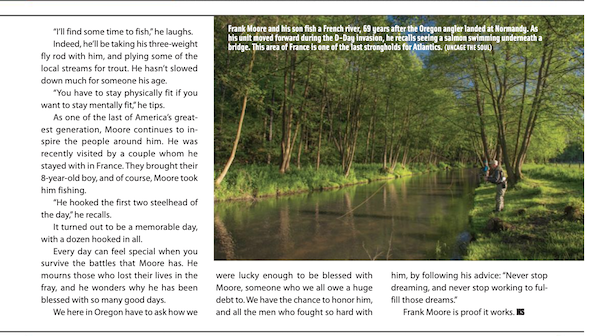

As his unit, an anti-aircraft battery, made its way off the D-Day beaches through Normandy, he was struck by the many fine fishing streams he saw. While crossing a bridge in Pontaubault, he spotted a huge salmon swimming in the Selune River below. Through the many decades that followed, he dreamed of returning to fish those waters.

And last spring, 69 years later, Moore stood on that same bridge, but with a fly rod in his hand instead of a rifle. His extraordinary trip back was the result of a year-long effort to fulfill his dream of returning to fish those streams. His incredible journey is the story behind the documentary Mending the Line which was released this spring by Uncage the Soul Productions. The Portland videography company helped raise the money through crowdfunding and accompanied the veteran, recording the historic trip.

Steve Engman and John Waller of Uncage the Soul traveled with Moore to Normandy. Like many other people, Engman was inspired by his story enough to take a hand in making it a reality.

“Words can’t describe it,” Engman says of the trip. “To be there as he fulfilled his dream.”

He says the French treated Moore with love and respect.

“It was great to see the appreciation and the understanding of the people.”

Moore says he too was touched by the overwhelming gratitude from locals.

“They do a good job of teaching their children history and culture,” he says, adding that the scars of the war can still be seen in the countryside.

“They are surrounded by the reality of it. There are reminders of history around them every day.”

Moore was honored at a memorial service at Utah Beach while in Normandy.

He was treated like the hero he is, although he doesn’t like that term.

“We didn’t feel like heroes, we just had to do it,” he says.

Horrific sights met the young man,who arrived at the Dachau concentration camp shortly after it was freed in late April 1945.

“I witnessed what the egotistical side of man was capable of,” Moore says, “man’s inhumanity to man. I couldn’t believe it.”

He describes starved bodies stacked 8 feet high and 30 feet long. Emaciated and listless, the living survivors looked little better than the dead.

HE HAS BALANCED the memories of those horrors against the good in his life, and if he was unfortunate to face the realities of war, he has been more than fortunate after it. Returning to Jeanne when the work was done, he helped start the historic Steamboat Inn on his beloved North Umpqua River, sharing the river’s magical scenery and majestic steelhead with the world. Shortly afterwards, he was also one of the first anglers to recognize the link between healthy watersheds and the rivers within them, and he battled to stop excessive and damaging logging in its headwaters.

One of Oregon’s most storied fly fishermen, he handles a fly rod as if he has had one in his hand his entire life, which he has. He served on the old Fish and Game Commission, and worked tirelessly to promote Oregon’s rivers and fishing. It was for this work that he was awarded the Gene Leo award.

Through it all he has been accompanied by his wife, Jeanne, and he still talks of her like many men speak of their young brides.

“The best day of my life was January 1, 1943, when I said two words: ‘I do.’”

Moore is as happy talking of their years together as he is talking about fly fishing.

“With her, every day gets better.”

He still stays active, and shortly after our interview he was heading to Colorado for the Telluride Film Festival where Mending the Line would be viewed.

Will he be doing anything else?

“I’ll find some time to fish,” he laughs.

Indeed, he’ll be taking his three-weight fly rod with him, and plying some of the local streams for trout. He hasn’t slowed down much for someone his age.

“You have to stay physically fit if you want to stay mentally fit,” he tips.

As one of the last of America’s greatest generation, Moore continues to inspire the people around him. He was recently visited by a couple whom he stayed with in France. They brought their 8-year-old boy, and of course, Moore took him fishing.

“He hooked the first two steelhead of the day,” he recalls.

It turned out to be a memorable day, with a dozen hooked in all.

Every day can feel special when you survive the battles that Moore has. He mourns those who lost their lives in the fray, and he wonders why he has been blessed with so many good days.

We here in Oregon have to ask how we were lucky enough to be blessed with Moore, someone who we all owe a huge debt to. We have the chance to honor him, and all the men who fought so hard with him, by following his advice: “Never stop dreaming, and never stop working to fulfill those dreams.”

Frank Moore is proof it works.