More Northern Pike, Shad Caught In Lake Washington

Two more pike were netted out of Lake Washington during now-annual spring tribal test fishing, while shad numbers nearly doubled over 2021’s catch, worrisome trends for the big Seattle watershed.

Neither species are native to the lake, but the continued presence of northerns – which could only have been illegally stocked here by an a**hat or two – is considered “disheartening.”

The concern is that if the species gains a foothold in Lake Washington, it could further reduce the survival of native fish populations such as salmon that support state and tribal fisheries and are regionally economically, culturally and environmentally important.

The lake’s young Chinook, coho and sockeye are already preyed on by a host of native and introduced predators – cutthroat, northern pikeminnow (a completely different native species), yellow perch, rock bass and others – as they navigate from hatcheries and spawning streams down through the lake and out the ship canal, resulting in poor survival rates and returns.

At least five pike have now been netted by the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe since the first turned up in early 2017, including two last spring. A bass angler caught and unfortunately released one in 2018.

Northerns are native to the upper Midwest and Canada and are a popular game fish there. They were illegally transported over the Continental Divide into Western Montana and subsequently spread down the Clark Fork and were placed in Lake Couer d’Alene before turning up in Washington’s Pend Oreille River and being flushed downstream into upper Lake Roosevelt. The Colville Tribes pay anglers $10 a head for them.

The latest two northerns in Lake Washington were netted the last week of May, according to MIT data forwarded by the National Marine Fisheries Service.

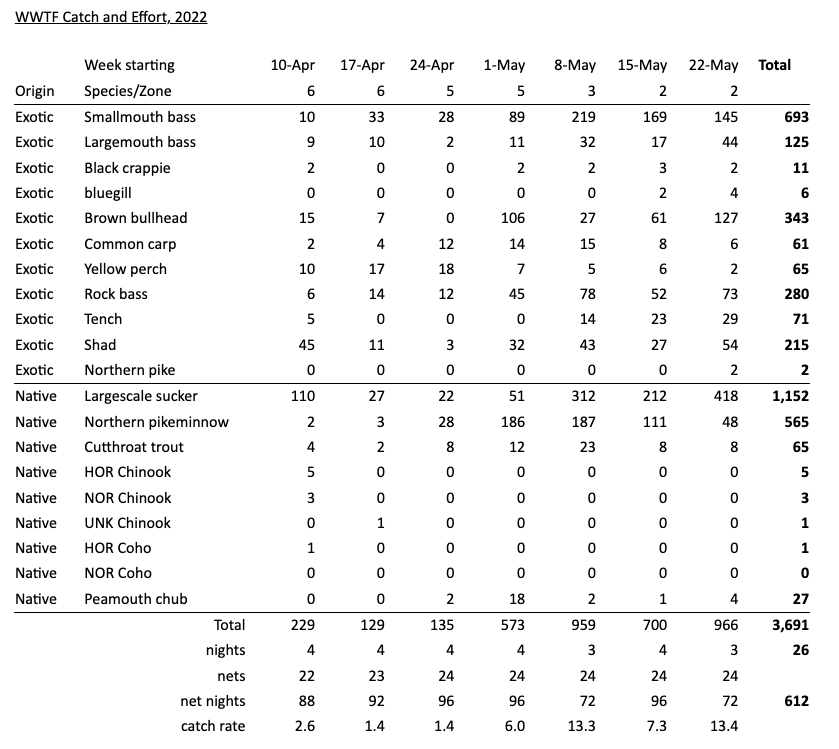

That weekly accounting of the tribe’s efforts also shows a total of 215 shad caught between early April and late May.

Shad are an East Coast species first introduced to California’s Sacramento River in the early 1870s and which then spread to and were also introduced in the Columbia system by the 1890s. They’ve occurred sporadically in Puget Sound since, but nothing to this degree.

It’s possible that the increase seen in Lake Washington from spring 2021’s 112 fish may be due in part to the gear used and where it was deployed, “but those don’t appear sufficient to explain all of the change,” per information from the tribe shared via NMFS.

Before last year, a total of just 28 shad had been landed in the lake in all of 2015, 2017 and 2018.

Catch per net night has risen from .02 shad those three years to .18 last year and .35 this year, per MIT.

“If this trend continues it has the potential to dramatically reshape the Lake Washington ecosystem,” states a tribal biologist, as transmitted by NMFS.

(MIT’s Lake Washington warmwater test fishery data is to be made available to the public under the annual salmon fishing package agreement between WDFW and Western Washington treaty tribes.)

In the Northwest, shad are most associated with the Columbia, which has seen record runs in recent years. This year’s count at Bonneville Dam – where there’s a popular sport fishery – currently sits just below 4 million, with 5.5 to 7.5 million seen annually since 2018. It’s believed that many more spawn in the lower river.

It seems intuitive that all those shad are impacting the environment of the Columbia system, competing for forage with young salmonids – and also possibly benefiting them – but a big report last year acknowledged that little is in fact known about the species and ultimately recommended a “systematic, multiyear research program” because “potential risks for the ecosystem and anadromous salmonids warrant caution and continued attention.”

Back on Lake Washington, this spring’s most caught species by Muckleshoot crews was again a native one, largescale suckers (1,152), followed by introduced smallmouth bass (693), native northern pikeminnow (565), and nonnative brown bullheads (343), rock bass (280), shad (215), largemouth bass (125), tench (71), yellow perch (65) and common carp (61).

No walleye were reported caught this year, but they have turned up in the past, in both MIT and WDFW nets. It was the discovery of a dozen walleye in 2015, including an egg-dripping 13-pound female, that essentially led to the tribal effort.

“Whoever illegally stocked walleye and northern pike into Lake Washington is no friend of warmwater anglers. They are even no friend to walleye anglers,” noted Bruce Bolding, WDFW’s warmwater manager before he retired several years ago.

Native fish represented 49.3 percent of 2022’s catch, nonnatives 50.7 percent (last year’s results were 69-31, native-nonnative).

Nets were soaked three to four nights per week, with 22 to 24 deployed over a total of 612 net nights. Catch rates varied from 1.4 fish per night in mid-April to 13.3 and 13.4 in early and late May.

The MIT test fishery is being performed to “collect additional information on the feasibility and potential impacts of a directed fishery (C&S and commercial) on invasive warm-water fishes in selected portions of the Lake Washington basin, a commercial fishery in the northern portion of Lake Washington, and associated research in Lake Sammamish to estimate population abundance of native and invasive piscivores.”

It is one of two efforts to gauge the watershed’s predator fish populations and what they’re eating. Another is looking at ways to reduce predation rates on juvenile Chinook, coho and sockeye as they rear in and transit through the lakes and ship canal.