Latest USGS Migrations Maps Feature Several WA, OR Deer, Elk Herds

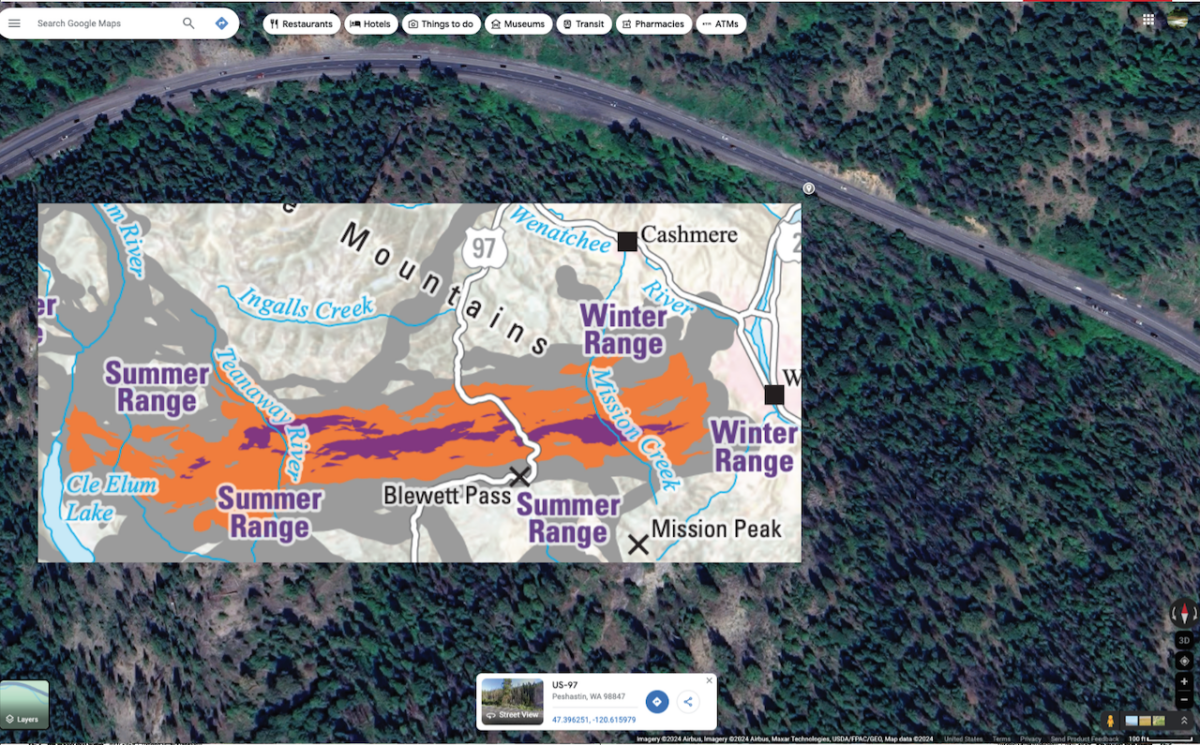

New mapping out from the U.S. Geological Survey today is spotlighting how heavily a Central Washington mule deer herd uses a migratory corridor intersecting with busy US 97 over Blewett Pass.

Building on previous mapping and based in part on 121 GPS-collared does whose locations were recorded every four hours, the data shows that the Wenatchee Mountains herd is particularly fond of crossing US 97 along the stretch immediately north of the pass where its three lanes wind down Tronsen Creek between tall ponderosas.

The slopes on either side also offer many “stopovers” for the deer, where they stay for awhile to graze on fresh forage or give birth before continuing their journey to summer range in the Teanaway and eastern Alpine Lakes Wilderness, then retrace their steps in fall.

Per the USGS’s Ungulate Migrations of the Western United States, Volume 4, the herd’s migratory corridor averages nearly 44 miles in length, with a maximum of 82 miles.

Bisecting that path is US 97, which links the Yakima and Wenatchee Valleys. It and another highway on the south side of Blewett “receive high volumes of traffic in the region and present semipermeable barriers to spring and fall migrations,” according to the 106-page publication.

Even as state data indicates that fewer roadkill salvage permits are issued here than other parts of Central Washington, the new mapping adds to better understanding the movements of this herd, just as for other deer, elk, pronghorn and moose across the Eastside and beyond.

“To best conserve and protect the habitat used by migrating elk, mule deer, moose and pronghorn, we have to know exactly where these species move across the landscape,” said Blake Henning of the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation in a press release about the release of USGS’s fourth volume. “That’s why this mapping work is so important – it’s to ensure their future health and well-being. We support and greatly appreciate the USGS and collaborating states and Tribes for leading this highly collaborative and globally significant effort.”

The ongoing migration corridor mapping project began in 2018 and was authorized by US Department of the Interior Secretarial Order 3362. It’s headed up by USGS wildlife biologist Matt Kauffman and includes field work performed by WDFW and numerous other state and tribal wildlife agencies.

This latest volume includes data on the Klickitat County mule deer herd, which has shorter migratory corridors, especially on their eastern end, than their cousins three counties to the north. These deer typically move from winter quarters along and above the Columbia into the Simcoe Mountains and face similar and different threats.

“Increasing residential development in the western half of the range, and renewable energy development and conversion to viticulture in the eastern half of the range, are the greatest concerns for winter ranges and migration corridors. Additionally, U.S. Highway 97 is a semipermeable barrier to migration and only has one wildlife underpass, which was built in 2012,” Ungulate Migrations states.

At the other end of US 97 in Washington, private funds were used to help improve wildlife passage at Janis Bridge for central Okanogan County mule deer.

The Colockum elk herd is also featured in the new volume, as are Oregon’s Beulah-Malheur, Klamath Basin, Murderers Creek, Northside, Southeast, South Wallowas and Trout Creek mule deer herds.

Past volumes from USGS et al have detailed Chelan mule deer, Selkirk whitetails and Pend Oreille elk, as well as Okanogan County’s Methow mule deer herd. With funding from RMEF and USGS, a fifth volume is on the way.

Last year, ODFW also put out a mini-magazine that talked about how migration corridors of deer east of the Cascades have become more chopped up. The decline of habitat connectivity and other factors are all acting in concert to slowly suck the life out of herds there.