Western Big Game Migration Corridors, Habitat Loss Spotlighted

Important migration corridors used by Western big game and other wildlife are getting national attention, as is habitat loss.

Department of Interior Secretary Deb Haaland today announced a package of grants and matching funds tallying nearly $10 million that will be distributed to Washington, Oregon, Idaho and four other states and three tribes for 13 projects that are part of the Improving Habitat Quality in Western Big Game Migration Corridors and Habitat Connectivity program.

“No one state, tribe, or federal agency can restore and conserve wildlife corridors on their own. To be successful, we must get our resources, science, various tools, patchwork of lands, and our collective will to do our part in ensuring the best habitats for wildlife,” said Haaland in remarks noting that migratory paths for critters are one of a half-dozen special focuses of the Biden Administration’s America The Beautiful Initiative.

In the Evergreen State, $530,100 will go toward using virtual fence technology – basically, wireless fencing like you would use to keep your dog in your yard – to “control cattle on 47,700 acres in the shrubsteppe habitat of mule deer, sharp-tailed grouse, greater sagegrouse, and pronghorn” in the Columbia Basin.

In Oregon, $414,600 will be used to continue work along Highway 97 including 10 miles of fencing to funnel mule deer and elk to underpasses south of La Pine and in doing so help better connect a 75-mile migratory corridor.

And in Idaho, $716,000 will help big game more safely cross busy US 95 in what is known as the Panhandle Complex Priority Area between Sandpoint and the Canadian border.

Some $2.5 million of the overall funding package came from federal agencies and private sources as part of Trump Administration Interior boss Ryan Zinke’s Secretary’s Order 3362, with the other $7 million matched by state agencies, tribes and conservation groups receiving the money.

“We appreciate that this Administration remains committed to SO 3362 and recognizes the importance of big game migration corridors and seasonal ranges. We hope that this support also means the Department will continue to commit significant funding for SO 3362 habitat projects and big game migration research in fiscal year 2023 and beyond,” said Joel Pedersen, Mule Deer Foundation president and CEO in a press release. “Through the leadership provided by the Department and working collaboratively with state fish and wildlife agencies, SO 3362 has proven to be a highly successful landscape conservation initiative that is benefiting economically and ecologically important big game species, but also the hundreds of other species that depend on the same habitat.”

On a related note, Washington’s state legislature earlier this year also pledged nearly $2.75 million to engineer and install a wildlife undercrossing on Highway 97 south of where volunteers using donated funds have already produced solid results.

Today also saw the U.S. Geological Survey release Ungulate Migrations of the Western United States, Volume 2, meant to inform transportation, wildlife, land and other planners about the migratory needs of mule deer, elk and pronghorn herds.

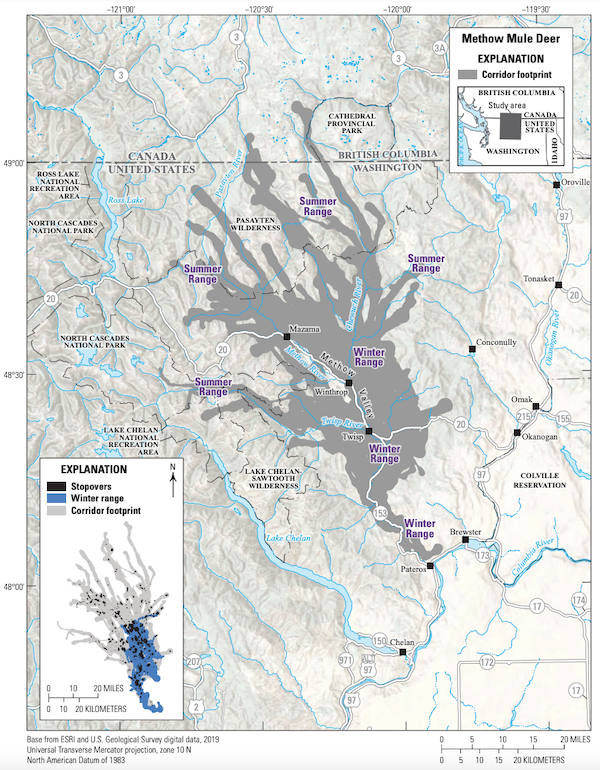

Among those highlighted is Northcentral Washington’s Methow Valley muleys, the western members of the West Okanogan herd, the largest migratory group in the state.

Maps detail the overall footprint of these far-roaming deer, including their winter range on the valley floor and its foothills from Winthrop to Pateros, critical late spring stopover areas for pregnant does, and summer range in the heights along the Cascade Crest, Sawtooths, Tiffanys and Pasayten – even 10 miles across the international border in British Columbia’s Cathedral Provincial Park area.

The profile was based on 2017-20 data from 128 radio-collared does that found median dates of their spring migration ran from April 24 to May 16 and the fall migration from October 14 to 23. The mean migration length was just under 29 miles, with some deer moving as few as 3 miles and others beating feet 65 miles.

Today’s news also follows on a report last week from the National Wildlife Federation that game species lost an average of 6.5 million acres of “vital habitat” over the past 20 years, with mule deer losing 7.3 million acres.

Why does that matter? Less habitat simply equals fewer bucks, does and fawns.

Aaron Kindle, NWF’s head of sporting advocacy, called habitat loss “a very real threat to our sporting future, and … we need to utilize all tools in the toolbox to incentivize the conservation of native landscapes and the restoration of degraded areas. We hope this report shines light on these issues and spurs investment as soon as possible.”

The report puts the blame on “development-driven habitat loss, including transportation and energy development, conversion to agriculture, and urban sprawl.”

According to NWF calculations, Washington mule deer lost over 244,000 acres of habitat, while Oregon’s lost 242,000 acres and Idaho 166,000.

Also taking hits were elk (229,000 acres in Oregon, 168,000 acres in Idaho, 161,000 acres in Washington), mallards (235,000 acres in Washington, 192,000 in Oregon, 164,000 in Idaho) and mourning doves (229,000 acres in Washington, 214,000 in Oregon, 150,000 in Idaho).

“It’s time for hunters and anglers to lead again so these same wildlife species do not suffer again,” the report stated.