Why Migration Matters So Much For Oregon, Northwest Mule Deer

You may have heard me say this before, but with all of our deer hunting coverage, the October issue of Northwest Sportsman is one of my absolute favorites of the year to put together. Yet something’s been missing each fall, and I’m rectifying it this season.

So, alongside MD Johnson’s three interviews with Oregon and Washington statewide deer managers and noted Beaver State author and expert hunter Gary Lewis, my summary of Northwest biologists’ regional top prospects, Troy Rodakowski’s tips for hunting the back end of Oregon’s mouth-wateringly late-running blacktail season, Dave Workman’s shared wisdom from decades in the deer woods, Buzz Ramsey’s advice for tracking wounded game, Chef Randy King’s venison Bourguignon recipe and more, I want to talk about my oversight.

IN A WORD, it’s habitat. Since we’re highly unlikely to have hatchery deer anytime soon, it more than anything else determines how many bucks are available on the landscape for us each fall.

Yes, weather, drought and disease play roles too, as the past 10 years and especially the past five will attest. And predation can have localized impacts. I’m not looking forward to the days hungry wolves and starving deer herds are concentrated together on deep, snowy range for an extended period of time.

But it all begins with healthy habitat, which begets healthier does that beget healthier fawns that have better odds of surviving that critical first winter and being able to run away from predators, over time begetting more deer on the land and more available for harvest.

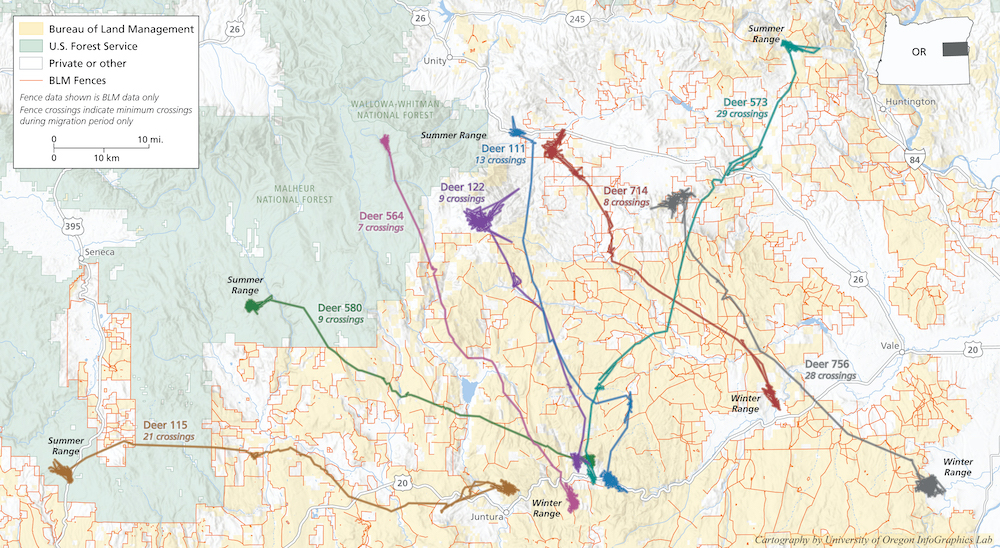

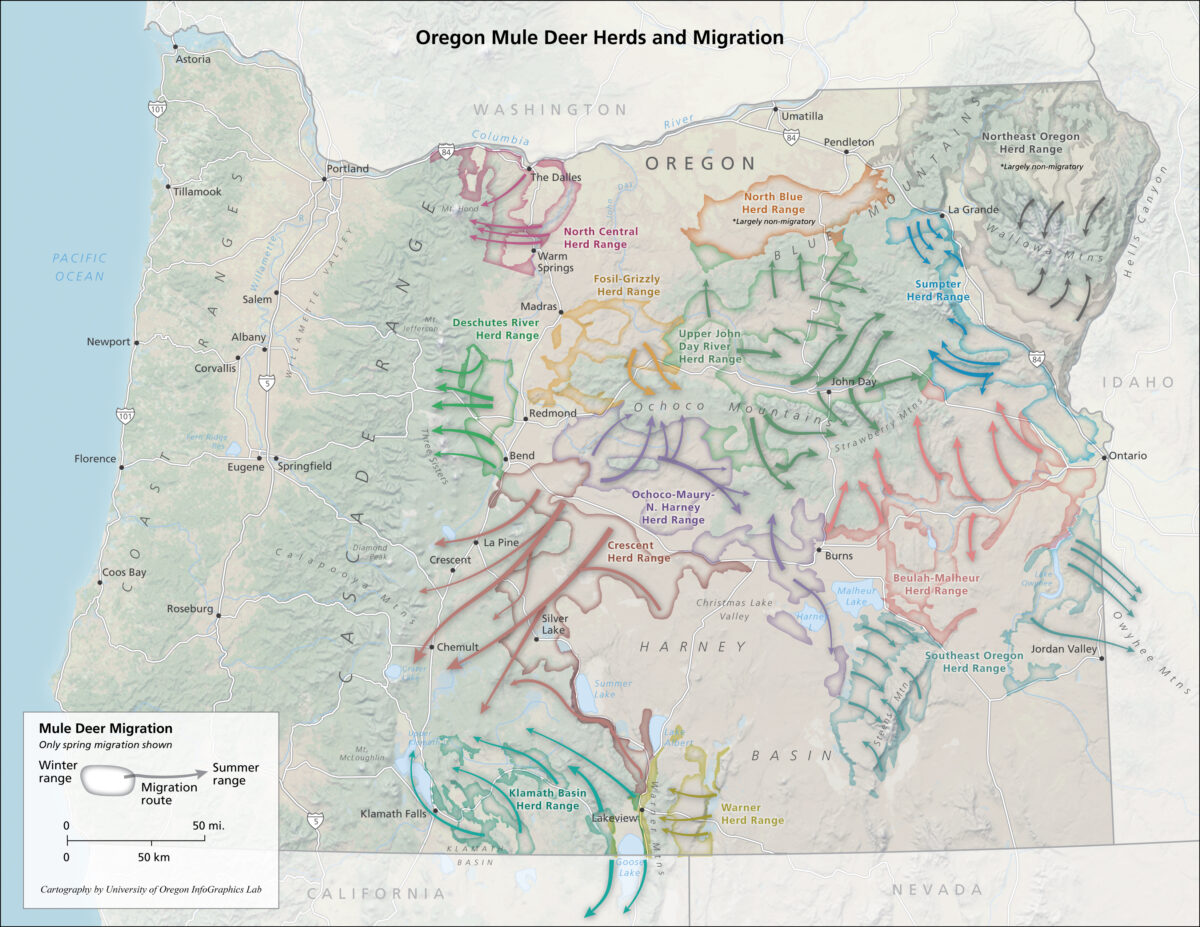

The problem, however, is that that good habitat is being chopped into pieces that are smaller and less accessible for mule deer all the time. This is especially true for migrators, which represent large portions of the herds in central and eastern portions of Oregon and Washington.

It really came home to me last month, when the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife published a very interesting new mini-magazine titled Migration Matters: The migratory journeys of mule deer in Oregon. It states that where once muleys could easily flow across wide-open landscapes on their annual rounds, tapping into critical spring and fall greenups and lush summer range and protected winter quarters, these days those habitats and corridors “are being fragmented by roadways, fencing, housing developments, agricultural uses, and energy developments.”

And as those impacts only increase – building traffic volume as well as more housing and thus disturbance, for instance – it’s becoming more and more challenging for the long-term viability of the herds so many of us hunters have such strong connections to.

NOW, I CONSIDER myself to be a student of mule deer, having hunted migratory bucks since the mid-1990s, but I did and did not quite realize how locked into their seasonal rounds – biologists use the word “fidelity” – these deer are. According to Migration Matters, they take “nearly identical” routes between winter and summer ranges each year, a behavior “transmitted culturally” from does to their fawns.

Maps plotting the course of two different migratory does show them taking practically the exact same paths back and forth for three years in a row. It recalls stories from my Northcentral Washington hunting camp of well-used deer trails beaten into the forest. But what isn’t being passed from generation to generation so well – or can’t be – is how deer can get around modern bottlenecks, which puts them even more in harm’s way.

“As residential areas expand, as new fences are erected, as traffic increases on roadways, and as new energy facilities are built,” say the authors, “it becomes increasingly difficult for mule deer to follow their migratory routes, and the benefits of migration, including access to higher quality forage, and subsequently, higher survival and greater reproductive success are lost.”

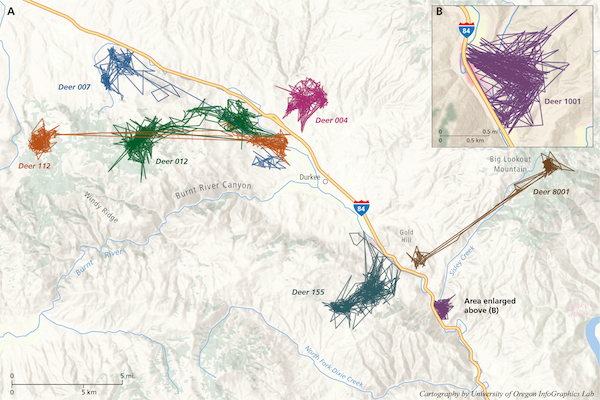

They call roads and fences “two of the most pervasive barriers” to mule deer migration, reporting that one study in Southcentral Oregon found they caused 30 percent of known mortalities there. And as roads get busier and busier, they essentially act as impassable fences, becoming “a complete barrier to mule deer movement, severing historic migration routes, separating groups, and cutting off deer from their former seasonal ranges entirely.”

A map of seven different collared deer show them repeatedly turning back as they approach a very remote stretch of I-84 in far Eastern Oregon, locking themselves into slivers of their herd’s former habitat.

It ties in with author Ben Goldfarb’s latest book, Crossings, How Road Ecology is Shaping the Future of our Planet, which is helping to detail the impact to a wider audience.

MULE DEER ARE in a slow, long-term decline across the West. While there are population spikes when good weather and forage align, those and the dips are trending remorselessly downward across time. Oregon’s herd has decreased by almost 50 percent over the past 40 years, reports Migration Matters.

Again, I do worry about four-legged predators – including the high dietary overlap of wolves and cougars in Washington’s Okanogan, home to that state’s most important migratory herd – but I think there’s a much more insidious one stalking the West’s mule deer that we should really be worried about, and that’s what I see as Migration Matters’ central point. The combination of roads, fences and development reducing habitat and connectivity, along with hotter and drier summers, invasions of nonnative grasses and junipers, and forage that is declining in nutritional value all act like a vampire to slowly suck the life out of our iconic deer.

The combination of roads, fences and development reducing habitat and connectivity, along with hotter and drier summers, invasions of nonnative grasses and junipers, and forage that is declining in nutritional value all act like a vampire to slowly suck the life out of our iconic deer.

The publication doesn’t mention poaching, but an April article on Central Oregon Daily quoting an ODFW official termed it a “huge part” of why doe survival is 10 percentage points below the 80 percent needed for a stable population. The illegal killing of the does also means there are fewer deer that still remember how to navigate to better habitat, driving herd health and productivity further down still.

Yes, things are being done to try and slow the overall decline, including reinforcing to the public the problems with poaching, and building wildlife crossings like those on US 97 between Bend and La Pine and, further north on the highway, an underpass between Tonasket and Omak. Dedicated, ongoing state funding is lacking, however.

There are also wildlife-friendly fencing designs and collaborative efforts across land-owning parties – federal, state and private – to make the corridors between ranges more passable. And Department of the Interior Secretarial Order 3362 is also pouring federal money into better understanding migratory paths and improving winter habitat.

“The more research that is completed on the remarkable journeys made by mule deer each fall and spring, the clearer it becomes that migration is critical to maintaining mule deer populations throughout the West,” states Migration Matters. “In Oregon, as in other western states, ensuring the long-term survival of mule deer populations means ensuring the long-term survival of mule deer migration, and a commitment to enhancing and protecting the habitats and wide-open spaces necessary for migration to continue for years to come.”

There aren’t easy answers to bringing the herds back up, but better understanding the real challenges the deer face and how to address them is a good starting point. Wherever you plan to migrate to hunt this month, I highly recommend mulling this easy-to-read, well-illustrated 28-page pamphlet, alongside the hunting advice and tips we rounded up this issue. They go hand in hand toward becoming a more informed Northwest sportsman.