A Short History Of The Weird Wanderings Of Northwest Wildlife

Move over, Mt. Rainier moose, there’s a new claimant to the title Northwest’s Weirdest Wandering Wildlife – the wolverine that two anglers spotted this week on the banks of the Columbia River near Portland.

Not exactly prime wolverine habitat and ODFW reports the animal is likely dispersing, but then again one also turned up in 2020 on Washington’s Long Beach Peninsula, where it was seen dining on some washed-ashore marine mammal.

Wolverines, of course, are better known for hanging out in steep, snowy mountains, landscapes blasted by fierce winters and avalanches, not along the shores of a near-sea-level river where you’d run a herring for springers on a sunny late March morning. It’s the first wolverine seen in Oregon outside of the Wallowa Mountains, in the state’s northeast corner, in 30 years, according to ODFW

For the two lucky Portland fishermen who spotted it – call me! email me! I want to hear your story! – it will be a wildlife encounter every bit as memorable and uber-rare as the one that two bowhunters had in September 2021 deep in the North Cascades’ Glacier Peak Wilderness near the Cascade Crest (read: real, actual, verified wolverine country) when a family group of three wolverines chased down their buck and battled it off a cliff.

Indeed, as the Northwest’s foremost – read: self-appointed; also: only – chronicler of weird wandering wildlife, I’d have to give this week’s galactically gone-astray Gulo gulo a 12/10, with bonus points awarded it for choosing to be seen by anglers, a lot well known for, well, fish tales, exaggerations and the like.

Nobody, and I mean NOBODY IN THE ENTIRE MULTIVERSE, would have believed them if they hadn’t snapped a couple pics of the beast scampering along the shore – likely looking for a log to leap off of into their boat to eat their bait and their lunches and probably their legs too.

OK, so wolverines’ fierce reputation might be a wee bit overblown, but this latest sighting adds to the suggestion that these low-slung overgrown weasels are more footloose than any of us might think.

Back in spring 2018, a dispersing male turned up in the woods outside a development near Snoqualmie, a foothills bedroom community of Seattle more well known for a certain waterfall than alpine dwellers. Video of it left WDFW wildlife biologist Brian Kertson “extremely dumbfounded” about what it was up to. Sadly, it was run over not long afterwards trying to cross I-90 about 20 miles to the east.

But it all could be indicative of a growing population. The nearest known wolverine population to the Portland sighting is in Washington’s South Cascades. Mt. Rainier has seen two litters of kits born in recent years, Mt. Adams one before that.

Mt. Rainier is also where that cow moose turned up last December. It was caught on trail cam wading through snowdrifts on the road to Sunrise, becoming the first moose ever known to visit the national park as well as the entirety of Southwest Washington.

It was probably the same moose seen using a wildlife underpass near Snoqualmie Pass in August. The closest aggregations of Alces alces are in the Okanogan and Northeast Washington.

Since I reported on that I received a story pitch about a cougar that swam about three-quarters of a mile from the mainland over to Squaxin Island in Deep South Sound.

Child’s play, I say!

Two of my all-time favorite weird wanderers were the pair of bull elk that swam across harrowing Haro Strait to Orcas Island in spring 2018 and gave Uncle John Willis quite a start.

“Well, this morning I planned on going to town, but chose not to do that,” Willis told me matter of factly when I reached him at his family’s Olga homestead. “I looked out my window at my sister’s house and here are two bull elk eating leaves off of a filbert tree in front of her house. I was not quite ready to see two elk this morning.”

Then there’s the bull elk of Whidbey Island’s Strawberry Point, probably a wayward Skagit wapiti.

While blacktail deer are well known to swim between the San Juans’ myriad islands, it’s more rare for black bears to do so, but in 2017 and 2019 a bruin (or bruins) showed up near the home of Willis (who has since passed away) as well.

Back in the early days of this magazine, I put together a story about some of the early 2000s’ weird wanderers, including:

* A mountain goat spotted in a Northcentral Oregon wheat farmer’s field before it hunkered down on the banks of the lower Deschutes;

* Another goat that hung out in an Ontario onion farmer’s field before turning up on the John Day, a culvert in Sherman County and the cliffs along I-84 east of The Dalles, then swam the Columbia and climbed up Mt. Adams;

* A cow moose captured in Spokane, released 20 miles northeast of the Lilac City and roadkilled near Riggins, Idaho, south of Lewiston.

* And a bighorn ram captured on the north side of the Wallowa Mountains and that crossed over the rugged range’s Eagle Cap Wilderness in the dead of winter, then for good measure crossed back over just as spring began.

“That’s what males of every species do, they seek out new territories,” ODFW’s Keith Kohl told me at the time. WDFW’s Scott McCorquodale agreed. “The young males are just prone to dispersal. Probably it’s to maintain gene pools. But they will suffer higher mortality as a whole. Females don’t tend to do it as much. They tend to inherit their home range from their mom.”

One of the most interesting things that has come out of all of the intense tracking of Northwest wolves is just how far dispersers wander. None can match OR-7. Born in Northeast Oregon’s Imnaha Pack in 2009, it was collared in 2011 and over the next three years the device showed the wolf dispersing across the state into the region around Crater Lake before continuing into California and becoming indecisive about which state it wanted to settle down in. For awhile, if it lifted its left hind leg to pee, it was in Oregon; if it lifted its right hind leg, it was in California.

I exaggerate, only slightly.

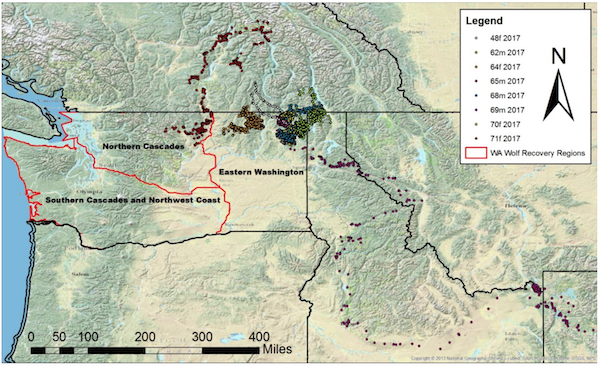

The paths of Washington wolves are no less interesting. Like “sparks from a campfire,” as it has been described, no small number have flicked out north into British Columbia, east into Idaho, southeast into Wyoming, across Oregon, and finally, in 2021, realized they can also go south into WDFW’s South Cascades recovery zone.

On a more serious note, USGS and state and other partners are documenting the important migratory corridors of Methow Valley mule deer – a few of which move as much as 65 air miles between their winter and summer ranges – and Central Washington muleys as well as whitetails and elk in the northeast corner.

And then there are weird congregations of critters I’ve reported on: a gathering of nearly 100 mountain goats on a Mt. Baker snowfield in 2015; a colossal raft of almost 700 sea otters spotted off Olympic Peninsula in 2016.

“We have no idea,” a USFWS biologist told me about what all the otters were up to. “We were all flabbergasted.”

And critters in weird places: A fox nonchalantly passed a couple climbers on Mt. Adams near the volcano’s summit.

A few years after the Yakama Nation reintroduced pronghorn to their Southcentral Washington reservation, a few antelope turned up in Garfield County near Pomeroy and I assumed they were one and the same. But WDFW biologist Paul Wik told me at the time that he believed the animals actually came up out of Northeast Oregon. Those in Washington’s Douglas County likely swam Rufus Woods Reservoir after being released by the Colville Tribes on their reservation.

Everyone knows the story of how mountain goats were brought from Canada to the Olympic Peninsula (and then in recent years mostly removed en masse to the North and Central Cascades). Less well known is the story of the goat that wouldn’t go – a mean old Mt. Baker billy that inexplicably turned up in a farmer’s field near Acme east of Bellingham, was eventually lassoed after quite the battle and then got drafted into that 1920s’ effort to create a hunting opportunity on Mt. Olympus, etc., but then died beforehand.

That was back in the era when Yellowstone elk were used to rebuild herds in the Northwest; a project to stock the Oregon Coast’s Siltcoos and Takhenitch Lakes with moose didn’t fair as well.

Fish go swimabout as well. A few pink salmon turned up at Lower Granite Dam on the Snake and the Wenatchee River in 2021. Who the hell knows why. They’re far more well known in Puget Sound than the Palouse or the state’s apple capital.

Neotropical Pacific species like mahi mahi, opah, yellowtail jacks, shortbill spearfish, striped marlin and bluefin tuna are occasionally caught off the Northwest Coast, when water temperatures are to their liking.

(Of course, there are also some fish species that are not exactly welcome wanderers – northern pike in the Upper Columbia; walleye further and further up the Snake.)

And that’s not to leave birds out of this.

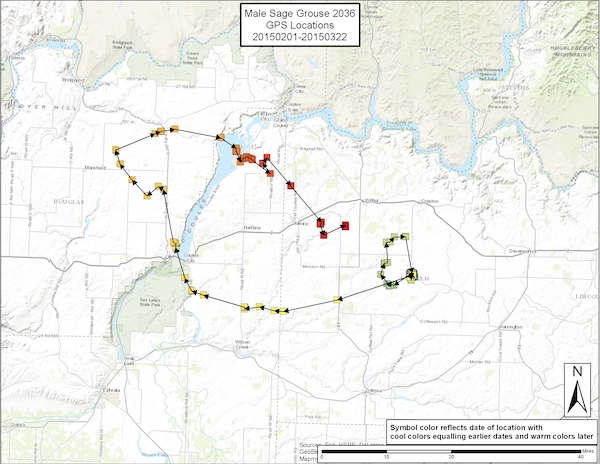

Back in 2015, I wrote about the gambolings of grice – a pair of GPS-tagged upper Columbia Basin sage grouse, one of which seemed to check out most of the townships between Grand Coulee Dam, Lind, Sprague and Reardan over a six-week span.

The other went all NASA-deep-space probe, using the momentum of a loop around its Lincoln County leks to slingshot west across the very southern end of Banks Lake and explore the northern recesses of Douglas County before looping back over Banks’ north end towards home.

“Movement is a really important part of these animals’ life history,” WDFW grouse biologist Michael Schroeder noted at the time.

Indeed, movement is pretty important to many animals’ life histories, and we’re learning that more and more, through old-fashioned VHF tracking, GPS devices that illustrate critical range and corridors, and, well, utterly random appearances by oddball species in totally unexpected places.