Northern Pike Netting Set To Begin On NE WA Waters

Annual northern pike suppression efforts are slated to begin soon in Northeast Washington and anglers and local residents are likely to see boats out gillnetting for the unwanted apex predators over the coming weeks and months.

Work will be focused on Long Lake – also known as Lake Spokane – west of the Lilac City, Pend Oreille River impoundments to the north and sprawling Lake Roosevelt.

State and tribal fishery managers don’t want the invasive species to gain any more of a foothold in waters home to important resident fish – and potentially salmon and steelhead – and have been actively removing them for more than a decade now, with at least 40,441 killed so far.

Staci Lehman, a WDFW spokeswoman based in Spokane says the work typically occurs from March to June and is timed to coincide with the pike spawn in nearshore shallows.

Operations will start on Long Lake this month and primarily focus on the upper end of the impoundment, from the McLellan Conservation Area – where the reservoir forms a big upside-down U opposite Tumtum – upstream to Nine Mile Recreation Area, she says.

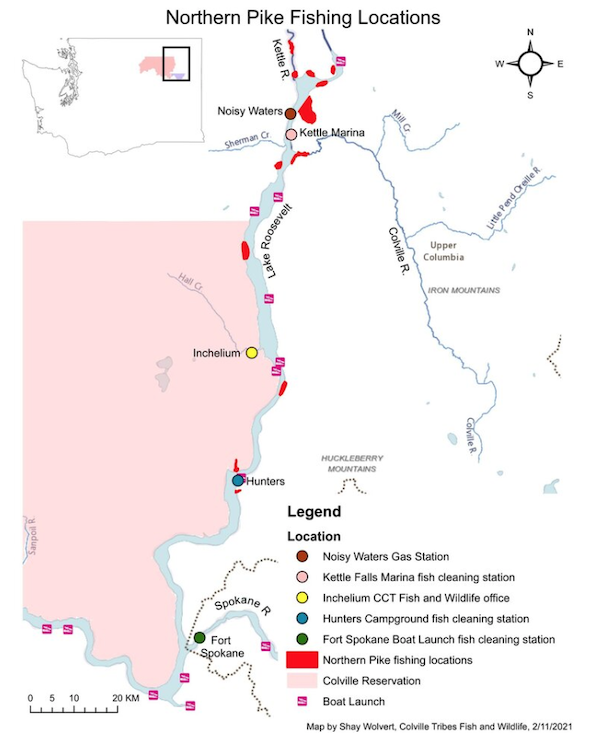

In April, as days and water temps warm and the reservoir begins to refill, efforts will shift to Lake Roosevelt, where WDFW partners with the Colville Tribes and Spokane Tribe to tamp down pike populations. The state agency and Kalispel Tribe work together on the Pend Oreille River.

Lehman says the gillnetting is “highly visible” and often sparks questions from the public.

Anglers typically express concerns about bycatch of rainbows and walleye, which provide popular sport fisheries. Past years have seen low incidental catches of both species, with state biologists saying cold water temperatures also help survival rates of trout that are caught and able to be released.

In an early February radio segment, Holly McLellan of the Colville Tribes defended gillnetting, calling it the “go-to method” for removing pike while avoiding bycatch.

“It captures the most fish and it’s the least amount of effort for us,” she told John Kruse of Northwestern Outdoors Radio. “So we can set a net in the day and let it fish overnight and come pull it the next day. They’re pretty effective. We’ve got it down to where we know the best mesh sizes to capture the fish in, we know the best net material and the certain types of habitat to set the nets in to target pike. So we are really trying to stay away from bycatch and other fishes. We’re really just trying to target northern pike.”

Sometimes known as water wolves, pike have “a voracious appetite for fish, particularly soft-rayed fish like trout and salmon,” according to Lehman, and when they’re moved outside their native waters, they can cause “large-scale changes to fish communities – in some cases leading to elimination of entire species,” she says.

Alexander Creek, a formerly productive Chinook system in Southcentral Alaska that once hosted eight fishing lodges during the run, has been closed to king harvest since 2008 after pike invaded the system and sharply depressed salmon returns. Rainbow trout and grayling fishing also had to be closed on this Susitna River tributary north of Anchorage.

Back in Northeast Washington, a recent photo of a netted northern with a similar-sized burbot in its jaws illustrated the problem and the tenacity of pike.

“To our surprise, even when we pulled the net up out of the water, the pike did not let go of this burbot. The pike had the burbot’s face in its mouth,” McLellan told Kruse. “That’s one of the other native fishes we’re trying to protect … Burbot are also native in Lake Roosevelt and Eastern Washington, and they’re a prehistoric fish, been around with the white sturgeon, which is also another prehistoric fish, back when the dinosaurs were around. So these fish are very important to us as well. We don’t want them to go extinct because they’re preyed upon by these nonnative fishes. So yeah, that burbot was fighting for its life there.”

WDFW’s Lehman says that along with reducing pike impacts on resident fish, another goal of suppression efforts is to limit the odds of pike getting into the so-called anadromous zone of the Columbia, used by ocean-going stocks such as spring and summer Chinook, sockeye, summer steelhead and other populations.

If pike get there – a 6-pounder was caught within 10 miles of Grand Coulee Dam in 2018 – it “would put at risk the billions of dollars invested into the recovery of salmon and steelhead populations,” Lehman says.

Upper Columbia tribes are also working to return Chinook above Chief Joseph and Grand Coulee Dams, built without fish ladders.

Biochemistry analysis showed that many pike in the Pend Oreille and Upper Columbia/Lake Roosevelt have a high relationship to northerns in Cave and Medicine Lakes, side waters of Idaho’s Coeur d’Alene River, and thus in all likelihood they illegally arrived in the system via buckets or livewells.

Anglers can cash in on northerns via a Colville Tribes’ sport-reward program that pays $10 per head of fish caught in the Columbia from Wells Dam to the Canadian border, the Spokane River up to Little Falls, and the Kettle and Okanogan Rivers.

Last year saw fishermen turn in 125 pike heads, scoring $1,250.

According to WDFW, 19,430 pike have also been removed from Box Canyon Reservoir on the Pend Oreille River since 2012, mostly in the first three years of the program but 814 last year. Just downstream, 825 have been removed from Boundary Reservoir since efforts began in 2016. At Long Lake, 1,076 northerns have been netted since 2020. And per a late January article in the Colville Tribes’ Tribal Tribune, Lake Roosevelt comanagers have removed 19,110 from the reservoir since 2015.