WDFW Commissioners Briefed On Potential Wildlife Area – Former Centralia Coal Mine

As Washingtonians have a chance to weigh in on whether WDFW should acquire a former Lewis-Thurston County coal mine for wildlife habitat and recreational access, Fish and Wildlife Commission members took a gander at the proposal today.

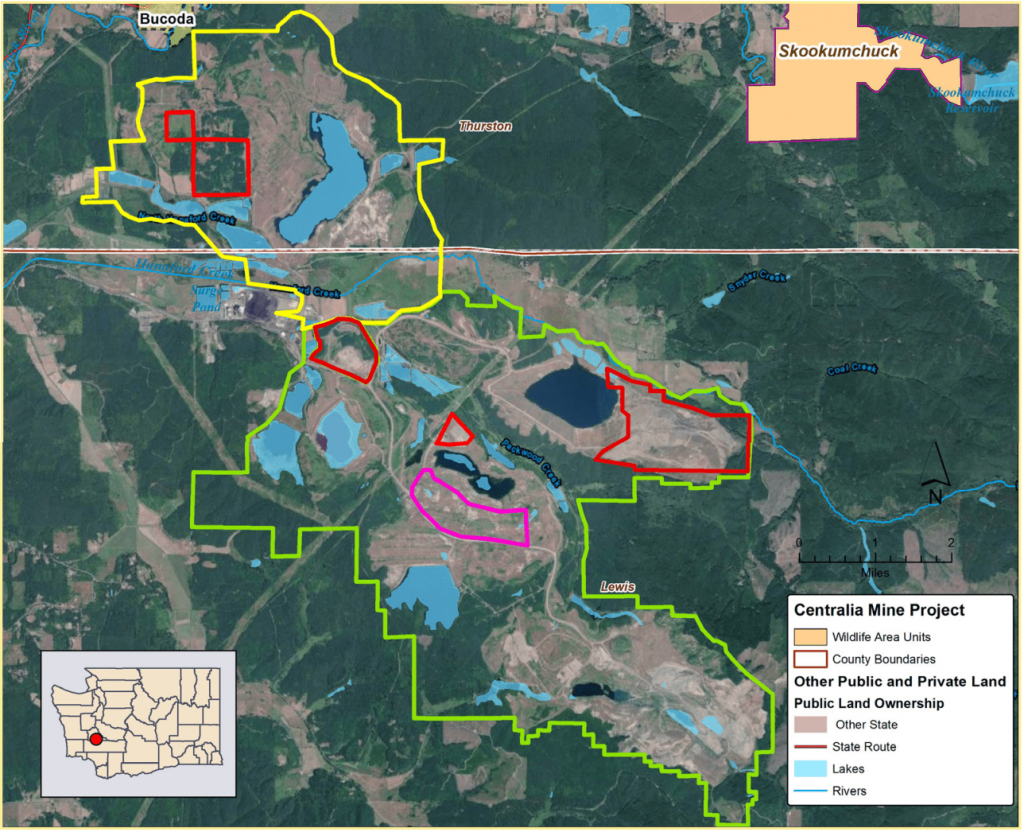

They expressed excitement about a potential “showcase” land reclamation project and were pleased that two-thirds of the 9,600-acre parcel east of Centralia could be donated to WDFW, but they also encouraged agency staffers to look at the deal with a very “critical eye.”

Those thoughts came this morning during a meeting of the citizen panel’s Wildlife Committee as commissioners heard from real estate and regional managers Cynthia Wilkerson and Brian Calkins.

The duo detailed how TransAlta quit mining here in 2006 and has been in talks with WDFW about taking over the lands as the Canadian company also reclaims the hills and valleys that were strip mined of an average of 9 billion pounds, or 4 million tons, of bituminous coal annually as recently as the late 1990s and early 2000s.

WDFW envisions a mosaic of habitats providing a home for everything from current residents like elk to reintroduced populations of imperiled species like Oregon spotted frogs, western pond turtles and streaked horned larks.

Sitting at their first meeting on the Fish and Wildlife Commission, recently appointed members Fred Koontz and Lorna Smith weighed in strongly in favor.

Smith, of Port Townsend, said it has “the potential to be a showcase” for WDFW and nationally “for how you do these reclamation projects,” while Duvall’s Koontz called it a “great project” and said he “shared the enthusiasm” for it.

Public access would be opened in phases as the site is cleaned up, and WDFW is working with TransAlta and the federal Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement to ensure that toxic soil is removed.

That industrial legacy was on the mind of rancher Molly Linville. The commissioner from Moses Coulee said that she understood fellow members’ excitement, but she also worried about “dirty dirt” coming around to “bite us in the keister.”

She also pointed out that it’s expensive to manage ground.

“I feel cautious about this based on how clean the property will be and how much it costs to maintain,” Linville said.

Commissioner Jim Anderson of Buckley acknowledged that acquiring the land was “quite an opportunity. They don’t come around like this too often.”

But he was also not afraid to look a gift horse in the mouth. He encouraged WDFW staffers to use a “critical eye,” “a sharp pencil” and “hardnosed thinking” in evaluating the deal.

It’s anything but a done one. For another week WDFW is taking public comment one way or the other on this and five other proposed acquisitions. Afterwards, those that rise to the top will compete for state grant funding from Washington lawmakers.

That’s how the agency has acquired wildlife areas like the 4-O, Big Bend and Simcoe Mountains in recent years.

While TransAlta would donate 6,500 acres of the mine, it wants to sell the state the other 3,100 acres.

Cost estimates aren’t made until the grant process. It’s also unknown at this time what the tax bill and annual maintenance would be. Unkempt lands in Western Washington turn into blackberry, Scotch broom and dandelion festivals.

But if it all comes to fruition, the site would be the largest wildlife area on dry land in Western Washington.

Wilkerson, the real estate manger, pitched it to commissioners as “a pretty phenomenal opportunity” that had been on state radar for many years.

Calkins, the wildlife manager, said it offered a chance to restore “high-quality habitat” and WDFW was working with TransAlta to keep wetlands in place and open more grasslands.

He said it could be a showcase for how impacted land can be restored and enhanced for wildlife and people.

“We really feel like this is a project we should pursue,” said Calkins.

In response to Anderson’s concerns that “donations rarely come without strings,” he said that two WDFW teams were working on the technical and policy aspects.

Mining ended when it became cheaper for TransAlta to fuel its two generating stations here with coal shipped from Montana and Wyoming. Last December one of those stations was shut down and the other is slated to cease operations in 2025 per a 2011 state agreement to phase out coal.

For its part, TransAlta appears eager for the mine to become a wildlife area.

“The acquisition of this property by WDFW aligns with TransAlta’s commitment to sustainability,” said the company’s Mickey Dreher. “We believe a longterm wildlife area is the best use of this property and would greatly benefit the community now and into the future.”

The other options are, essentially, for it to revert to commercial timberlands or perhaps be purchased by a local tribe.

Though the mine has been closed off to the public, some elk hunters will be familiar with it. WDFW offers a limited number of special permits for senior and disabled sportsmen to hunt part of the range of a herd of 400 wapiti that roams these parts.

In 2019, the last year data is available for, they enjoyed high success rates, with all eight hunters who reported their activities (10 permits were issued overall) tagging out on antlerless animals.

Given reduced public access to private timberlands in Western Washington, the state’s ever-growing population and the wisdom of providing habitat and recreation space for future generations of critters and humans alike, I think turning the old mine into the wildlife area is an intriguing idea, and I think it is also one with lots of questions to sort out.

Public comment is being taken through Feb. 5 two ways: via email at lands@dfw.wa.gov and via mail to Real Estate Services, PO Box 43158, Olympia, WA 98504.

Clarification, Jan. 29, 2021, 8:40 a.m.: The sentence on the cost-estimating process for grant funding submission has been tweaked. That occurs when the project is submitted for state funding.