WDFW Talks Puget Sound Chinook At Special New Early NOF Meeting

North of Falcon kicked off a month early last night as WDFW held a special new meeting to talk about Puget Sound Chinook management with anglers and others.

The two-and-a-half-hour town hall included updates on ocean conditions, the challenges of holding mixed-stock fisheries, straightjacketing Stillaguamish Chinook payback provisions in the new Puget Sound harvest management plan being implemented this year, a look back at what (the hell?!?) happened during last summer’s fisheries, and a chance to ask agency managers pointed questions and offer ideas for 2024.

For close observers of the annual salmon-season-setting process, there wasn’t much they wouldn’t have already known, but the Zoom session – recorded here and posted on YouTube – did attract 215 overall viewers, including 175 at its peak, and at least a few of the names of those who spoke up were unfamiliar to me, so it may have worked to help talk to a wider angler audience than the usual hardcore NOF junkies.

“WDFW had to make some difficult decisions on salmon fishing opportunity in the 2023 summer seasons in Puget Sound, particularly in Marine Area 11,” explained Mark Baltzell, the agency’s statewide salmon manager when asked this morning about the purpose and goal of the meeting. “We felt it was important to continue to try to inform our constituents about the complexity of management and the challenges we face in any given year trying to put anglers on the water.”

“We were intending to reach a wider audience of constituents who are new to salmon fishing or do not understand the process we go through each year,” Baltzell added. “At the end of the meeting, I think it was clear that there are still questions about how we manage these seasons and a desire from the public for more opportunities to connect.”

FOR THOSE HOPING FOR A SNEAK PEAK at this year’s salmon forecasts, there was only one reveal last night – the 2024 pink run is looking pretty grim (that’s a joke about the odd-year fish, folks) – but Dr. Marissa Litz’s look at ocean conditions was at least somewhat encouraging.

As we come out of a very, very strong but also apparently short-lived El Niño, Litz pointed out that it had followed three straight La Niña years, which tend to be “really good for Northwest salmon” and should have been favorable for Puget Sound smolts at sea.

And as those now adult salmon begin to point their noses back to the Skagit, Snohomish, Duwamish-Green, Puyallup, Nisqually and other rivers, the expected spring transition from El Niño to La Niña could help blunt the negative effects of warmer ocean conditions, she said.

It was left to Baltzell to be the clouds looming on either side of Litz’s silver lining.

He warned that perpetually struggling Stillaguamish Chinook would continue to restrict fisheries in marine areas, and/but that overall the agency would attempt to provide opportunities while staying inside ESA constraints and trying to meet conservation objectives and recovery goals.

Looking at recent seasons’ restrictions provides a glimpse of what the future may hold.

This won’t be news to San Juans Chinook fishermen, but some of WDFW’s slides last night really illustrated how, even as overall Puget Sound catches have stayed relatively stable over the past decade, there have been huge reductions in the islands’ expected harvests.

Where as many as 9,000 kings were expected to be caught in Area 7 in 2015, only 1,500 to 2,000 were expected to be in each of the last four seasons.

That’s in part due to the huge loss in winter blackmouth fisheries and guideline-drive summer seasons there, and because angling in Marine Area 7 is “really expensive” in terms of Stilly king impacts, Baltzell said. (Coded wire tags implanted in young salmon tell creel samplers their river of origin, allowing managers to model fishery impacts.)

That’s a critical concept going forward, and one I hope my fellow fevered fishery freaks continue to help flesh out to the public.

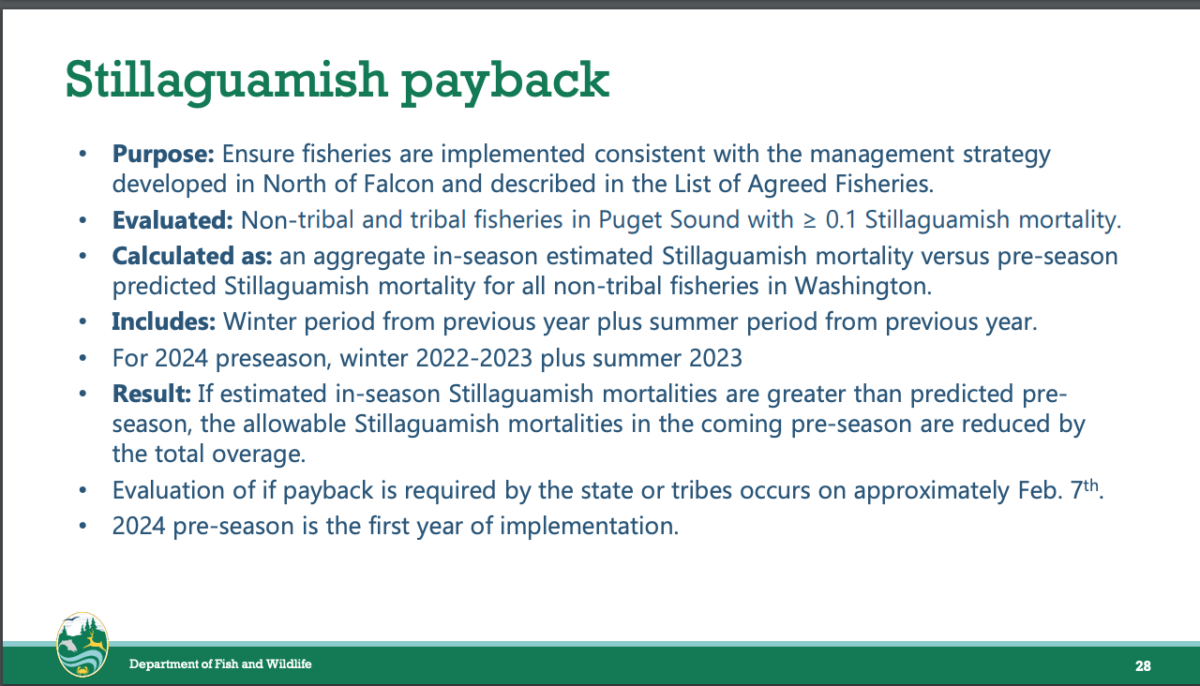

The aforementioned Stillaguamish payback provisions are part of the new Puget Sound Chinook harvest management plan, and while the document is still undergoing federal review, 2024 will be the first year it is actively implemented.

In a nutshell, the provision says that if too many of the Snohomish County system’s Chinook are caught one year (winter 2022-23 and summer 2023, in this case), the next season’s allowable mortalities will be reduced by that amount, and that affects marine waters the most.

I would guess that that was probably the key message WDFW wanted to deliver last night – this sobering new management paradigm.

One of the meeting attendees, David Hurn, naturally wanted to know, OK, what then besides reducing angler opportunity is being done to help increase Stilly returns.

Baltzell agreed that fisheries – both the state’s and the Stillaguamish Tribe’s – had gone as far as they could to help out (WDFW salmon modeler Dr. Derek Dapp added that Canadian fisheries had been reduced as well), and said that the river is also the subject of big habitat restoration projects, staff time and state legislative support to try and rebuild the run, efforts outlined on web pages and YouTube videos and elsewhere.

Yet as responsible and well-meaning as all of that sounds and feels, the road to recovery is as steep as Mt. Pilchuck as it looms over the Stilly’s North and South Forks, if a brutal October 2023 paper from a NMFS contract researcher is any indication.

It found that it likely will be pretty difficult to increase Stillaguamish wild spawner abundances through habitat restoration due to “extremely low” marine survival and climate change impacts that are expected to decrease their numbers even more. And the report said that modeling suggested supplemental hatchery releases couldn’t offset the effects of global warming either.

It did advise looking further into what’s killing smolts in Puget Sound and what can be done about it. Harbor seal predation has been found to be “likely impeding the recovery of salmon populations,” according to a state science panel, but not at the mouth of the Stillaguamish, according to WDFW.

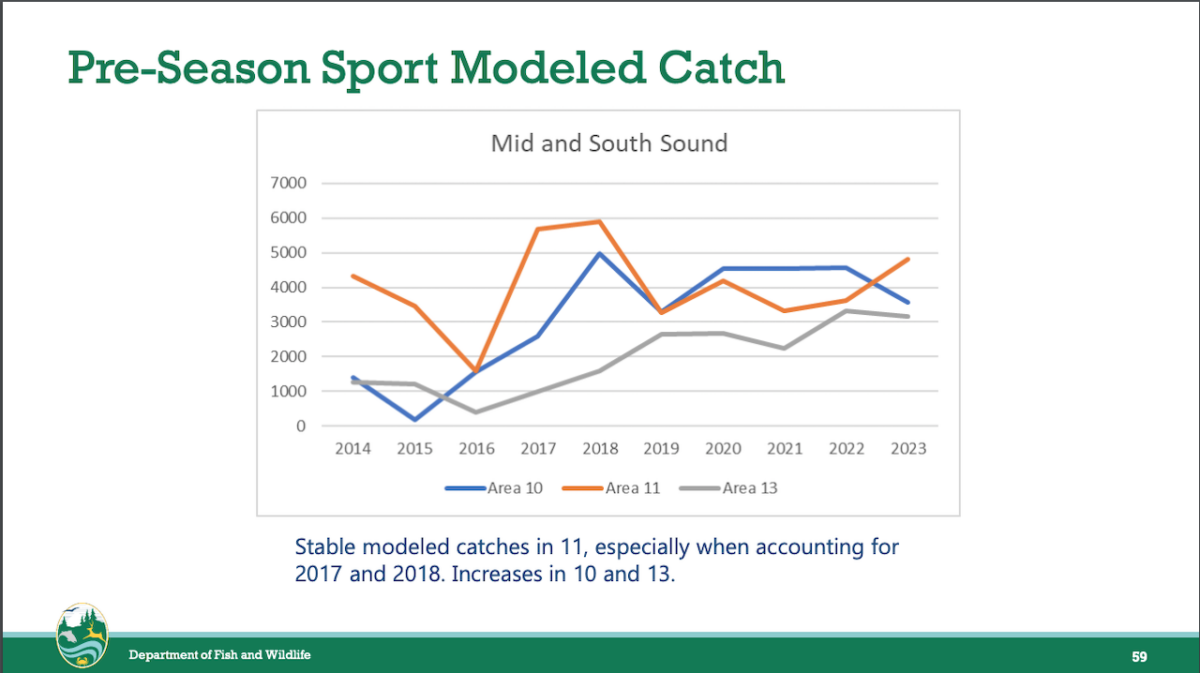

WHERE EXPECTED CHINOOK CATCHES IN THE San Juans, Admiralty Inlet and waters between Whidbey and Camano Islands have been decreased in recent years, there’s been a general increase in expectations in Areas 6, 10 and 13, WDFW’s graphs showed.

“What we’re seeing is a redistribution of catches,” Baltzell noted.

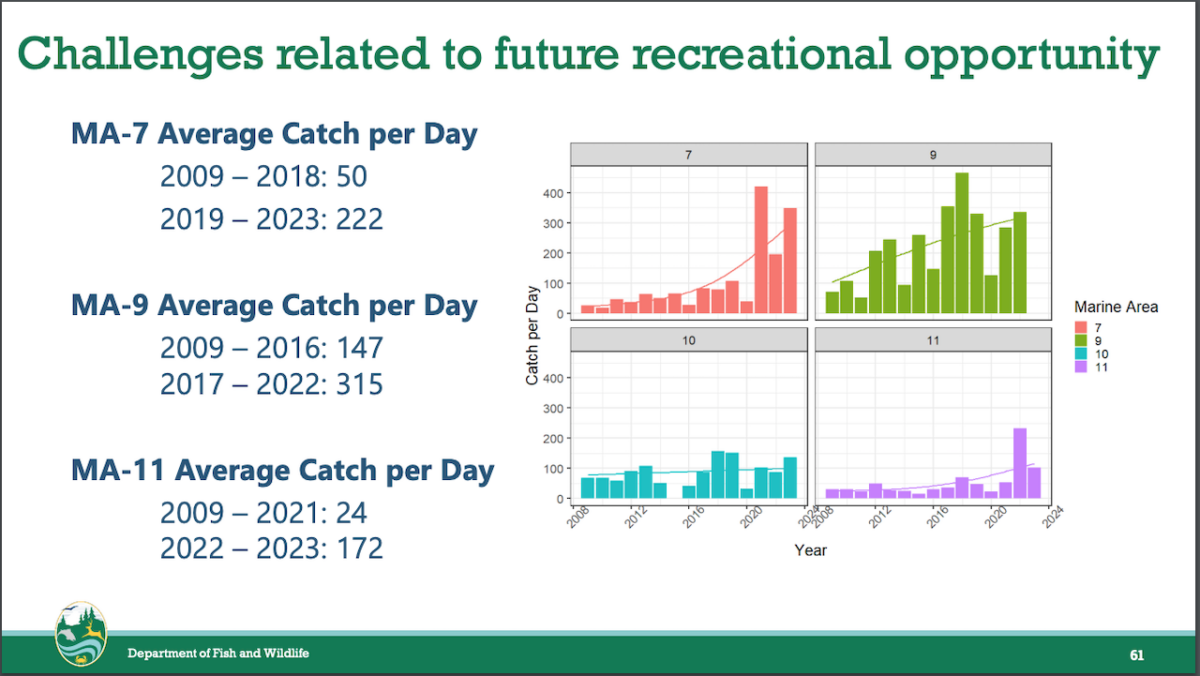

WDFW is also seeing sharply increased actual daily average Chinook catches throughout the inland sea.

Graphs showed harvests jumping from an average of 50 fish a day in Area 7 from 2009 through 2018 to 222 a day from 2019 through 2023; from 147 a day in Area 9 from 2009 through 2016 to 315 a day from 2017 through 2022; and 24 a day in Area 11 from 2009 through 2021 to 172 a day in 2022 and 2023.

Baltzell attributed that to “increasing effort and catchability” of the fish and a sport fleet that is tuned in to social media reports and willing to burn gas to get to where the fish are biting. Between that and shorter open seasons driving anglers to hit the water harder, encounter limits are being reached faster and faster.

Speaking of, encounter limits were the subject of a pointed question from Gabe Miller, a WDFW Puget Sound sportfishing advisor. He’d done his homework and wanted to know specifically what Chinook stock was being protected by last June’s unmarked encounter limit for Marine Area 11, which was shut down after just eight days of fishing. He said the fishery, located near one of two large local sporting goods warehouses he buys tackle for, had a low impact on Stilly kings.

Put on the spot, Baltzell couldn’t say specifically which one was – Dapp later said there had been concerns about Chinook from the nearby Nisqually – but he spoke to operating in a “sword of Damocles” atmosphere in the form of the risks now associated with exceeding impacts from season to season and those payback provisions.

And he said that sometimes it’s about reaching agreements with the comanagers and sticking with them.

That’s something of a handy dandy all-purpose get-out-of-jail card, and WDFW brass moved the Q&A portion of the meeting along to Kolby Stewart, who encouraged managers to implement more gear restrictions on the fishery such as requiring bigger hooks and bigger lures to keep sublegal fish off the line and preserve impacts. He also proposed a maximum size for Chinook.

The agency has been studying the effect of different gear on catches in recent years and has seen seasonal and area-specific differences, but Dr. Kristin Simonson said a blanket approach probably wasn’t the way to go, while Baltzell said that in 20 years of managing salmon he couldn’t recall hearing of a slot limit.

Randy Geoghagan wanted to know why WDFW didn’t just allow the large returning classes of Whatcom Creek and Samish River hatchery Chinook seen recently to continue upstream, seed the gravel and create more fish instead of essentially wasting them by stopping them at the facilities and only spawning a set amount.

It’s a popular theory in Northwest anglerdom – crank up the hatcheries! put hatch boxes on all the streams! – and I’ll be the first to say, given the headwinds this pragmatist sees, giddyup.

But then there’s that whole federal Endangered Species Act listing of Puget Sound Chinook thing.

“I don’t think more fish equals more opportunity when we’re limited by wild Chinook impacts,” stated Baltzell. “It’s the amount of wild fish that we impact and kill” to access those hatchery fish that matters the most in the equation.

Researcher Geoff McMichael asked if WDFW has considered a limited-entry approach that was equitable and would improve the experience. He said the crowds on Central Puget Sound were insane and suggested anglers with even Wild ID license numbers could fish one day, odds the next.

Baltzell said staffers had bantered the idea around and noted the Game Division did it through the special hunting permit draw. But it would present an enforcement headache on large marine areas like Admiralty Inlet, where there isn’t enough staff to monitor and make sure it was anglers’ day to fish.

Scott Douglas, a longtime Area 11 and 13 angler, expressed deep frustrations about their recent management. “There’s got to be a better way,” he said.

Brett Costanzo said Area 11 should be opened at the same time as Areas 9 and 10, which would essentially force salmon anglers to decide where to fish between the three, not hopscotch up and down the Sound, and he also advocated for a volunteer work program that completion of would allow for the keeping of one unmarked Chinook a year.

Peter Manning asked WDFW to reopen Whidbey Island beaches later in the season after coho hatchery goals are met, and Baltzell said they would look into it.

Manning also wanted fishing for winter blackmouth reopened around the island, which helped to feed local families, he said. Baltzell said those seasons were expensive in terms of impacts on Chinook stocks of concern and that anglers overall wanted to burn those on summer fisheries targeting returning adults.

Alex Van Hine asked WDFW’s position on recent reports that British Columbia trawlers had dumped 26,000 Chinook landed in their nets overboard – trawl bycatch is a huge sore point in the wider angling world right now. Baltzell said the state of Washington had no authority over the Canadian government.

Van Hine also encouraged anglers not to get discouraged and to stay involved.

Jesse Levine asked for WDFW’s thoughts about shifting to more terminal fisheries. Baltzell termed it “a great question” and something they had been thinking about for some time and would need to be strategic about – he pointed to the success of the Tulalip Bubble in Area 8-2 – but it would also complicate math assumptions around current whole-marine-area management.

George Hu, a relatively new salmon angler that WDFW would have been trying to attract to last night’s meeting, noted last year’s above-average Chinook and coho counts at the Ballard Locks and how that might have better informed reopening marine fisheries in nearby marine waters. Kyle Adicks, WDFW intergovernmental salmon manager, said that with all the separate stocks swimming through Puget Sound at the same time, there was no way to sort them out inseason.

Joseph Vannier felt that tribal fishermen were getting 75 percent of the fish in Area 11 and sport anglers weren’t getting their fair share. Adicks said tribal fisheries are generally focused in terminal areas, where impacts are focused on few stocks, whereas recreational Chinook impacts are burned in more mixed stock fisheries. Baltzell added that WDFW was endeavoring to make postseason catch reports more available to the public.

AT 8:30 P.M., WITH THE MEETING ALREADY 30 minutes over its planned two hours, Director Kelly Susewind summarized what WDFW had heard, thanking attendees for investing their evening with the agency and said they recognized the frustration.

He stated that his staff knew the fisheries, participated themselves and fought for them, and that they knew the legal and biological constraints that seasons are held under.

Susewind said their ears were “wide open.”

Whether WDFW makes this new January NOF meeting an ongoing thing remains to be seen, but next up in the process is that state and tribal managers will evaluate whether the Stillaguamish payback provision is required in early February, finalize the forecasts later in the month, and report out run expectations starting February 28 with Willapa Bay and Grays Harbor and March 1 with the rest of Western Washington.

Public discussions and tribal negotiations then run into mid-April, when 2024-25 seasons will be set.

For more, see WDFW’s North of Falcon page.

And that is going to have to be all the time I have for the “brief blog” I thought I’d be writing this morning.