Where WDFW’s At On Harbor Seal Predation Of Salmon

The sexy stuff today was 2023’s salmon numbers, some of which – Puget Sound coho and pinks, coastal silvers – look pretty enticing, but Washington fishery managers also used the North of Falcon forecast reveal to update anglers on other fronts to get behind.

Chief among them: keeping the momentum going towards doing something about harbor seal predation on Endangered Species Act-listed Puget Sound Chinook that is “likely impeding the recovery of salmon populations,” according to a Washington State Academy of Sciences report out late last fall.

Don’t expect anything big or anything soon, WDFW policy director Nate Pamplin cautioned the audience repeatedly, but he and agency legislative director Tom McBride were looking for support from fishermen as they take on the “incredibly conservative” Marine Mammal Protection Act.

“This is going to be a pretty massive process,” Pamplin told those attending today’s North of Falcon meeting, whether in person at a community center in Lacey or via Zoom. He said action was neither imminent nor something WDFW could fill out a NMFS form and 60 days later get a permit.

WSAS’s report came out of Governor Inslee’s 2018 Southern Resident Killer Whale task force and essentially kickstarted a look at harbor seal numbers on the state’s outer coast, Strait of Juan de Fuca, San Juan Islands, North and South Puget Sound, and Hood Canal, the status of those populations, and what they’re gnawing on.

There’s much more to it, of course, but to cut to the chase, the researchers came to three key – and carefully worded – conclusions:

“The preponderance of evidence supports the hypothesis that current populations of pinnipeds are likely impeding the recovery of salmon populations in Washington waters. As such, strategic lethal removal of pinnipeds is an approach that may be required for understanding the magnitude of impacts of pinnipeds on salmonids, either at local scales or at the ecosystem scale.”

“…the status quo [without intervention]…could further depress salmon populations..”

“…removals may be ineffective where pinniped populations are dense and there is the potential for other individuals to replace removed animals.”

Addressing the fishermen in front of him and watching online – many of whom have in fact had seals take salmon off their lines or followed their boats or kayaks in hopes of poaching one – Pamplin said none of the findings would surprise them but it was also “nice to have an independent scientific body come to that conclusion.”

He also took pains to clearly enunciate what WDFW was mulling at this point:

“It’s not a population reduction; it’s dealing with problem animals.”

“This is not a cull – far from it,” as MMPA doesn’t allow culls.

“We’re not proposing a cull or a bounty.”

“Very surgical removals in areas there are problems.”

In that way it might be very much like what is being performed on Steller and California sea lions at Bonneville Dam and Willamette Falls, pinchpoints where the pinnipeds enjoyed free lunches until state and tribal managers received federal authorizations to take out specific animals confirmed to be feeding on salmon or steelhead.

In the case of lethal removals at the falls, doing so drastically decreased the odds that at least one Willamette Basin winter steelhead run would go extinct if nothing was done to stem hungry sea lions.

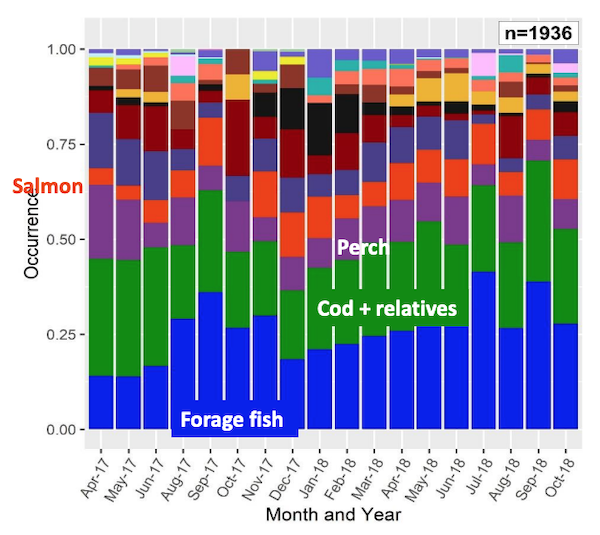

Salmon are a relatively small part of harbor seal diets, Pamplin acknowledged, but when you’re talking about over 25,000 stomachs on the outer coast, 15,000 in northern inside waters, 2,200 in the South Sound and 3,000 in Hood Canal, it adds up to no small portion of the 45 million Washington Chinook smolts headed to sea each year. Given the small size of those young fish, seals have to eat more to meet their dietary needs.

Per Pamplin, there are several management options under MMPA, all with varying degrees of difficulty.

Fishery officials could apply for a waiver of the act’s take moratorium to manage harbor seals, something that’s been granted and used fewer than 10 times, across the country, Pamplin said.

A former marine biologist for the Makah Tribe, he recounted how the “people of the cape” applied for a waiver to hunt eastern Pacific gray whales way back in 2005 and despite a pair of environmental impact statements and a federal judge’s involvement, 18 years later they still don’t have a permit.

He used that as an example of needing to build and maintain the political will to target harbor seals across multiple presidential administrations – generations might be more like it.

Another avenue in the MMPA is that Washington could request the feds turn over management of seals that are at their optimal sustainable population, or OSP, a critical legal term, to the state. That would include outer coast, northern inside and South Sound stocks, but not Hood Canal.

Only problem? Describing it as something of a technical option on the books, Pamplin stated it’s never been done before.

Then there’s MMPA’s Section 120 approach, which allows for the lethal removal of individual pinnipeds shown to be having a “significant negative impact” on at-risk salmon.

Perhaps with this in mind, biologists have been paying particularly keen attention to seal predation on Stillaguamish Chinook, a perpetually fishery-constraining stock (this year’s forecast is up somewhat from last year, drawing a “woo-hoo” from a WDFW manager, but also a reminder from a former state biologist that this year’s wild escapement is still half 2000-06’s).

WDFW and the Stillaguamish Tribe have been surveying the Stilly’s estuary by shore, boat and plane, capturing seals and outfitting them with GPS tracking, following along behind them with doggie bags for scat sampling, and checking returning Chinook at the hatchery for seal scars.

Bottom line?

“Predation is not a limiting factor,” said Pamplin.

It can clearly be elsewhere – cough, cough, Herschel et al, who et all, cough, cough – but another problem Pamplin pointed out is being able to identify particularly gluttonous seals. It’s easy to spy on specific sea lions snarfing Chinook and steelhead from elevated perches at Bonneville Dam or, say, along the Oregon City waterfront, more problematic with seals on the vast sweep of Puget Sound.

“The MMPA is a barrier in what we want to pursue,” he stated.

Still, WDFW’s tone right now is more “next steps” than “@$%$ it.”

Pamplin outlined a $945,000 request in WDFW’s 2023-25 budget to continue collecting seal abundance, distribution and diet information.

“”You’re not going to get an exemption to the Marine Mammal Protection Act unless you bring a lot of science,” McBride, the agency legislative director, told anglers.

Plans also call for coordinating with the Governor’s Office, Fish and Wildlife Commission, National Marine Fisheries Service, tribes, and state and federal lawmakers.

How well Pamplin rallied support among fishermen to the cause – a notoriously grumpy group to begin with that is also chafing at WDFW’s fishery decisions – remains to be seen, but he is making the rounds with the case, appearing on last night’s Fish Hunt Northwest broadcast for a segment with hosts Duane Inglin and Tommy Donlin.

And today he benefited from a tail wind of sorts in the form of generally positive – though not glowing – salmon forecasts well spread around the state. (What seasons those paper fish result in is still to be seen.)

Meanwhile, Pamplin will need to build a lasting, durable and wider coalition in support of removing some seals.

In some areas, that might be more nonlethal than lethal – making structural changes to the Hood Canal Bridge to address eddies that create a veritable buffet of near-surface-swimming steelhead smolts that can’t easily figure a way around the mile-long crossing and get eaten by seals; using TAST, or targeted acoustic startle technology, to drive seals away from chokepoints.

But elsewhere it would be about focusing on individual seals specializing in salmon predation and, using Section 120, focusing on those animals while leaving the rest of the herd to “go about their business.” That seems to be where WDFW’s at on this one.

And now to the last blog of the week …