With the official arrival of fall, it’s time to take a look at Washington’s 2021 gun deer and elk prospects.

The highlights: WDFW wildlife biologists in Chelan and Douglas Counties as well as the Blue Mountains are optimistic about mule deer hunting, while elk populations in the Willapa Hills are “very robust.”

The lowlights: Elk in the Blues are not doing well at all, and disease outbreaks and wildfire access restrictions may play roles for some hunters.

Go-time for muzzleloaders for muleys, blacktails and whitetails is this Saturday, September 25, followed by elk on October 2, while modern firearms hunters head out in search of bucks beginning October 16 and Eastside elk on October 30 and Westside wapiti on November 6, with late hunts also firing up in the 11th month.

Actually, members of both weapons types have already begun hunting, with some coming down from the heights of the Olympics, North Cascades and Pasayten with their High Buck harvests and/or very soaked gear following last weekend’s storms, but as we prepare for the bulk of this year’s seasons, let’s take a brief moment to look back at 2020’s hunt.

AS WE REPORTED BACK IN MARCH, last fall saw the highest Washington deer harvest since 2016 as nearly 10,000 more deer hunters than 2019 also took to the woods and fields of the Evergreen State, twin spikes likely due to rebounding herds and the boom in outdoor recreation due to the pandemic.

WDFW reported a total of 29,435 deer – including 27,655 during the general rifle, bow and muzzleloader seasons – were taken by 112,369 deer hunters (a 9.5 percent increase over 2019) who had an overall 26 percent success rate.

The increase in deer harvest primarily occurred east of the Cascades, with kill rising in Northeast Washington, Palouse, Blue Mountains, Okanogan, Chelan/Douglas and Klickitat/Columbia Gorge mule deer and whitetail districts, while important Westside blacktail hunting areas saw slight declines or were essentially on the same plateau as 2019.

Fast forward to this year and some of those same areas saw bluetongue and hemorrhagic disease outbreaks, particularly among whitetails near Spokane, Colfax and in and around Washington’s flagtail heartland, Colville, where there were concerns this year’s die-off could be as bad as 2015’s.

Recent rains may help that situation, and that and cooling temperatures certainly have helped restore access to wildfire zones in key areas of Okanogan and Chelan Counties, and the Blues, but you’ll still want to double check with the Forest Service and state land managers because there are still some closures.

As for elk, last fall saw hunter numbers rise statewide 3.9 percent to 56,581 and the general season rifle harvest went up 265 animals to 2,230, but the success rate dropped from 10 to 9 percent and the general and special permit take was down 201 bulls, cows and calves to 5,228 – the fewest taken since at least 2001 and likely many years before that, though that’s also a reflection of reduced permits following large harvests in the mid-2010s.

NOW, BACK TO THE FORECASTS. Kyle Garrison, WDFW acting deer and elk manager, says that overall, mule deer in six of seven management zones and whitetail deer in five of six management zones are at or above objectives. The outliers are Naches for the former species, though it has stabilized at a low level, and Columbia Basin for the latter.

As for blacktails, harvest appears to be stable across all five management zones, Garrison says.

Before late summer’s disease outbreak, whitetail hunting prospects were looking decent for Pend Oreille, Stevens and Ferry Counties, where harvest has been stable to rising slightly in most units, with popular Huckleberry and 49 Degrees North Units seeing more of an uptick than others, per WDFW biologists Annemarie Prince and Ben Turnock.

Only whitetail bucks can be harvested, but bids to reimplement antler restrictions or shorten the late rifle season were denied by WDFW and the Fish and Wildlife Commission earlier this year.

Note that after a fall without any game check stations, additional stops will be set up in Colville, Ione, Usk and Spokane to increase monitoring for chronic wasting disease. It’s not known to occur here, but has been detected in Northwest Montana. Please stop and have deer taken in Game Management Units 105 through 127 sampled.

Where whitetails west and south of Spokane are also being impacted by bluetongue, the somewhat overlooked and large mule deer herd in these mostly private parts is reported at near long-term averages, biologists Michael Atamian and Carrie Lowe say.

Fires on the Blues’ northeast side may impact hunting in the national forest – see the latest from the Umatilla NF – but overall prospects are good, thanks to recent easy winters.

“The district saw improvements in both total whitetail and mule deer harvests in 2020, beyond our expectations, and we expect this trend to continue into the 2021 season, especially for whitetail deer bucks that have a shorter lag time to become legal three-points than mule deer,” report biologists Paul Wik and Mark Vekasy. “Depending on the effects of the drought this season, we are still expecting mule deer harvest to improve through the 2022 hunting season.”

In the Columbia Basin’s big Beezley and Ritzville units, good posthunt buck and fawn:doe ratios last year have biologists expecting an average year for muleys.

The Okanogan is home to “improving postseason fawn:doe ratios and higher-than-average estimated fawn recruitment over the last two years,” and that could boost the number of 2½-year-old bucks available, per biologists Scott Fitkin and Jeff Heinlen

Heat and drought may keep them well up in the heights until forced down by snow, but things are expected to start getting white soon.

Of note, while this summer saw several fires burn in Fitkin’s district – Cedar, Cub, Walker, Muckamuck – he notes collar data from recent studies show just “modest short-term displacement from fire or little displacement at all; fidelity of individual deer to their summer range is high.”

Mild winters and rebounding herds has Chelan and Douglas Counties “2021 mule deer season … shaping up to be as good or better than that of 2020,” which was also the best back through 2016.

Along with pointing out migratory corridors north and south of the Wenatchee River, bios Emily Jeffreys and Devon Comstock suggest hunting the edges of 2020’s Pearl Hill Fire.

In the Klickitat, rising deer harvests and fawn survival back to average are good signs.

In Southwest Washington, deer hunting “should again be good,” say biologists Eric Holman, Nichole Stephens and Monique Ferris, with Coweeman, Lincoln and Winston Units all yielding a regional-best buck a square mile for rifle hunters in recent falls.

Harvest has been rising in the Mason Unit and generally steadyish elsewhere, but San Juans deer are suffering from a big disease outbreak, though it may better align the islands’ herds with habitat.

ON THE ELK FRONT, IT WILL BE another tough fall for most hunters in Eastern Washington due to continuing calf survival issues, with problems most acute in the Blue Mountains.

“The low number of calves being recruited into the population in 2021 will result in a low number of yearling bulls (spikes) available for harvest. This fall will be another below-average year for yearling bull harvest,” forecast biologists Wik and Vekasy.

Troubles with their herd sparked a large study this year involving the radio-collaring of 125 neonates to better suss out key factors in why elk numbers are declining.

As for the big Yakima herd, it’s not apples to apples because of surveying differences, but this past winter’s calf count at feeding stations was 27 per 100 cows, up from the “record low” of 19:100 the previous February.

“There should be improved harvest in 2021 over 2020, but still below average,” biologist Jeff Bernatowicz reported.

The Schneider Springs Fire should be well under control by the start of the late October season, but closures may still impact access to the Bethel, Bumping and Nile Units, so check ahead with the Okanogan-Wenatchee NF.

Northeast Washington elk aren’t surveyed due to thicker forest cover, but “increasing hunter harvest, documented expansion of elk distribution, and anecdotal information indicate that elk populations are stable and possibly increasing,” say Prince and Turnock.

Elk harvest across the more open Spokane and Palouse region has generally been rising in recent years, and there are areas of strong calf recruitment, such as Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge, but hunters will need to sort out access – whether through permission from farmers, permits from Inland Empire Paper or other sources – beforehand.

West of the crest, the elk kill in the western Willapa Hills is on a gradual longterm increase and without weather worries, should offer decent prospects, thanks to what Garrison calls a “very robust” population.

Take in the eastern Willapa Hills and South Cascades has been steady in recent years – Holman, Stephens and Ferris say to expect “generally less productive elk hunting” this fall – though below the highs seen a decade ago when high numbers of antlerless permits were available to reduce the size of the St. Helens herd and hoof disease may not have been as widespread.

Speaking of, hunters have an incentive to harvest limping elk in all Westside units and turn in the animal’s hooves for testing. Those who do could be drawn for special Westside bull tags next year if their sample is positive for TAHD.

Garrison says that North Cascades elk herd is “continuing to grow,” while the south Rainier herd may be seeing a decrease but it’s not definitive.

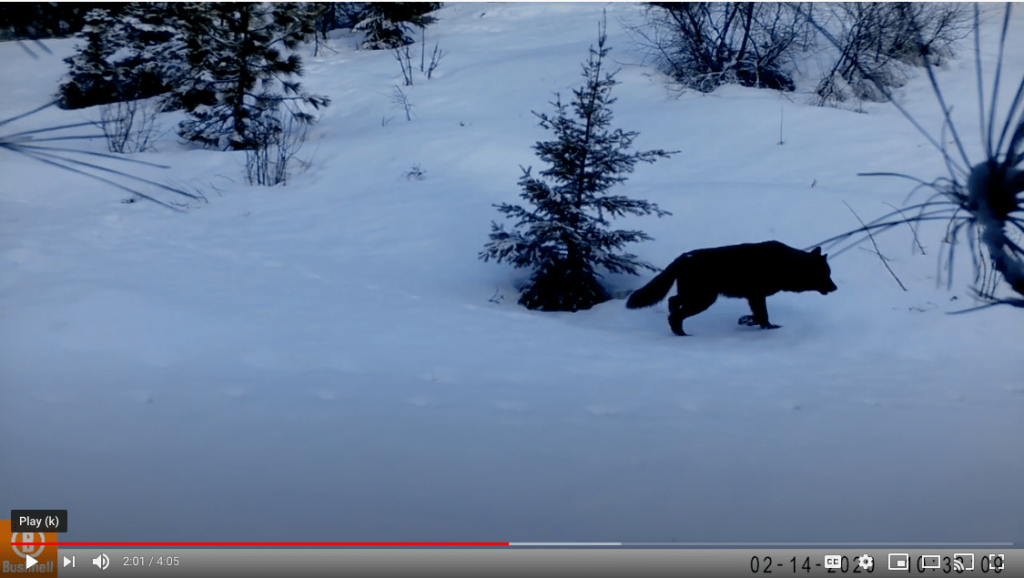

GARRISON ALSO CLAIMS THAT WOLVES are not currently known to be reducing Washington deer and elk herds where they overlap with the predators.

“We don’t really have any evidence of tangible, measurable differences on ungulates,” he says.

Only one WDFW-collared mule deer that was part of the joint agency–UW Predator Prey Project so far is known to be a wolf kill, says Garrison – only adults were collared, however, not fawns – while acknowledging carnivores do have impacts.

There were at least 176 known, counted, tallied wolves in the state at the end of last year, with many others roaming the woods, and their numbers can only have gone up through spring and summer. The state is also home to myriad black bears, cougars, coyotes, bobcats and a handful of grizzly bears.

When it comes to what drives deer and elk populations, it’s more of a “multifaceted equation,” says Garrison.

Variables include well-known ones like habitat quality and winter range disturbance, but also abiotic ones like hot, dry summers impacting forage quality and leading to animals with less body fat going into winter, which, if it’s a severe one, affects their survivability and success of pregnancies and thus herd numbers down the road.

“It’s not satisfying for people to hear that,” he allows. “Nobody wants to be powerless, but nature is in charge of dynamics.”

With Blues elk, the suspicion is that severe droughts and winters are contributing to poor elk calf recruitment, keeping the herds “consistently below objective.”

Still, it will be interesting to see causes of mortality in these wolf-, lion- and bear-rich woods for those 125 collared calves. Garrison says they will be monitored through the winter, with data analyzed next year.

And with the Predator-Prey Project in its final stages and researchers soon to begin their analysis, he’s also excited to see those reports when they start rolling out in 2022.

Indeed, it will be good to see results on all that, but for now, all eyes are on the coming two months of deer and elk hunting opportunities across Washington.