Oregon Mule Deer Predation, Hunter Harvest Webinar Coming Up

Two hot topics for Oregon mule deer hunters will be discussed during a Tuesday evening webinar – predation and harvest.

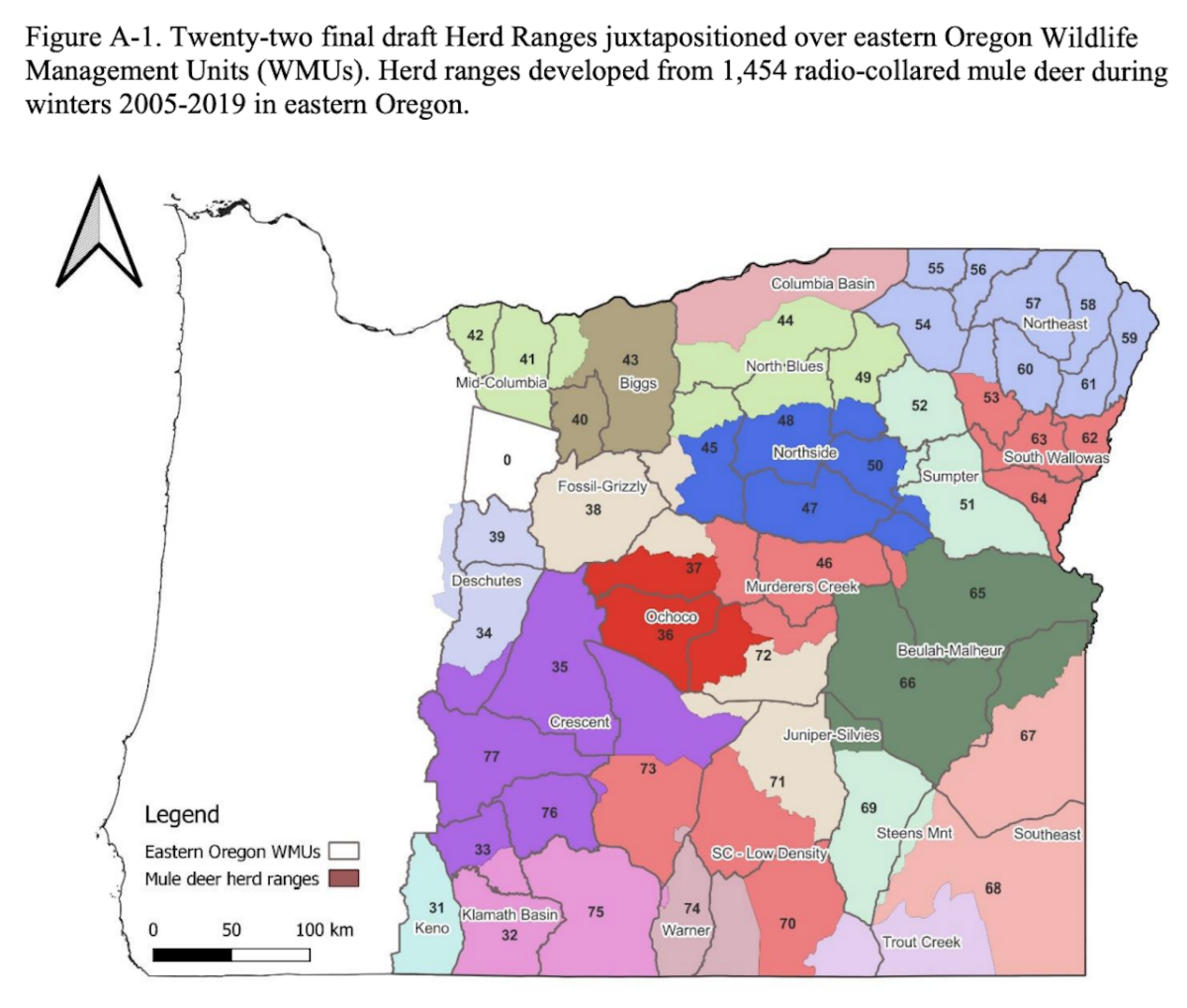

They’re the latest draft chapters unrolled in ODFW’s management plan update which, in part, aims to reset deer population and hunting objective baselines from the current wildlife management unit scale to one better mirroring local herds’ actual migration routes and ranges.

It’s the first rewrite of the plan since 2003 and the intervening years have seen a continued long-term decline for the state’s mule deer, but also new insights into the various herds’ habitat, health and habits.

“Recent data indicates current management objectives are set at an inappropriate scale (WMUs) relative to known mule deer movements (herds). Further, information from annual population monitoring, informed by recent ongoing research, suggest many mule deer herds in Oregon are nutritionally limited and may be at or very near a new, lower carrying capacity, or landscape potential,” the draft harvest management chapter states.

ODFW’s 6 p.m. webinar will include state wildlife biologists presenting on the topics, followed by a Q&A session.

Both new draft chapters make for interesting reading, especially the “complex” and widely varying influence of predation on mule deer populations and whether it is compensatory – meaning, the animal was going to die soon anyway but from another cause – additive – meaning, the deer otherwise would have lived – or somewhere in between.

While wolves are increasing in Eastern and Central Oregon, they “do not appear to be a significant source of mortality” for mule deer at the moment, says ODFW, which labels cougars as having “the greatest potential to (affect) mule deer populations.”

“Cougars readily take all age classes and cougar predation represents the biggest source of known mortality for adult females,” the agency states.

Coyotes are another significant source of mule deer mortality, especially newborn and young deer but also old does, according to the draft plan.

Efforts to boost deer survival by removing predators have been tried in Oregon and elsewhere in the West, but “the weight of available evidence suggests mule deer populations will not significantly improve through predator management alone.” That said, the strategy “may have a stronger impact” on herd recovery where the survival of adult does – the most critical and productive segment of the population – is being limited by predation, ODFW states.

The draft identifies work being done to better assess whether predation is additive or compensatory relative to other factors such as habitat, weather, and doe and fawn health limiting herd size, including in the Murderers Creek and Klamath Basins. And it says that in areas where cougar predation is limiting deer numbers, one strategy would be for ODFW to focus hunter effort in those areas to remove more of the big cats, as well as black bears in areas of high bruin density if they’re found to be reducing fawn survival too.

Predation of course is just one facet of the overall plight of Oregon mule deer, which have declined precipitously from as many as 300,000 in the 1980s to around 160,000 last year due to habitat loss and other factors. Hunter numbers have dropped from 180,150 in 1970, when there was a general season and high antlerless harvest, to 37,765 in 2022; harvest has plummeted from 67,413 bucks and 30,538 does in 1961 to 10,619 and 240 last year. All mule deer hunting is now by permit only and doe harvest is very restricted.

Going forward, ODFW is looking at more closely aligning population and harvest objectives and management around the true ranges of the various herds rather than the historical wildlife management unit overlay.

“On average, 25 percent of mule deer radio collared in eastern Oregon between 2011 and 2022 summered in a different WMU than it wintered in, with 40 percent of the WMUs having greater than 30 percent of the collared animals leaving the WMU. As a result, harvest monitoring data often do not align with population data at the WMU level. Observed levels of harvest that occurs during late summer and early fall can be much greater (than) winter population data indicate is sustainable,” the agency states.

Strategies call for developing new hunting boundaries based on mule deer landscape usage and allocating tags based on “animal distributions within herds during hunting season to distribute hunting effort and harvest monitoring.”

It will be interesting to learn how it all might impact tag levels, which are based on on-the-ground deer numbers, and how the odds of drawing a controlled permit might change with the creation of new hunt boundaries that may have more or less public or private land than before.