216 Wolves Counted In Annual Washington Survey

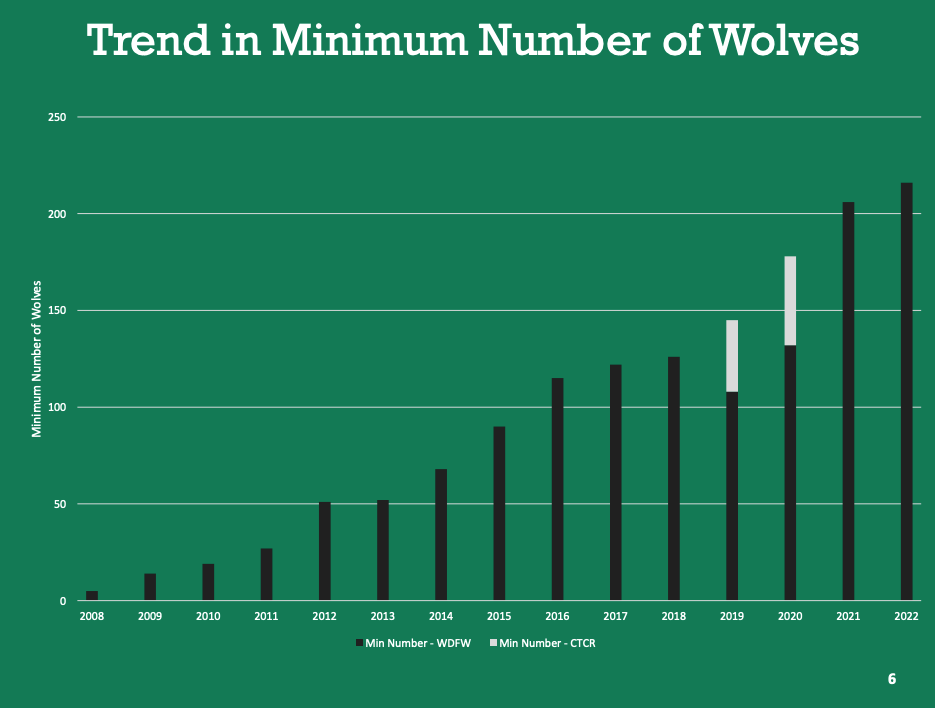

No surprise, but Washington’s wolf population rose yet again over the past year, marking the 14th straight year of growth, including a first pack in the South Cascades, “a fundamental leap forward” towards reaching state recovery goals.

WDFW wolf managers say there was a minimum – meaning, at the very least and highly likely to be many more – of 216 wolves roaming across the state at the end of 2022, 10 more than 2021’s survey found and reflective of a 5 percent increase over 2021 and a 23 percent annual increase every year since 2008, when the first modern-day pack was confirmed.

The number of packs and successful breeding pairs were also up, to 37 and 26, respectively, from 33 and 19 at the end of 2021, the agency reported in its annual report, posted this afternoon and put together in coordination with the Colville, Spokane, Yakama and Swinomish Tribes and USFWS.

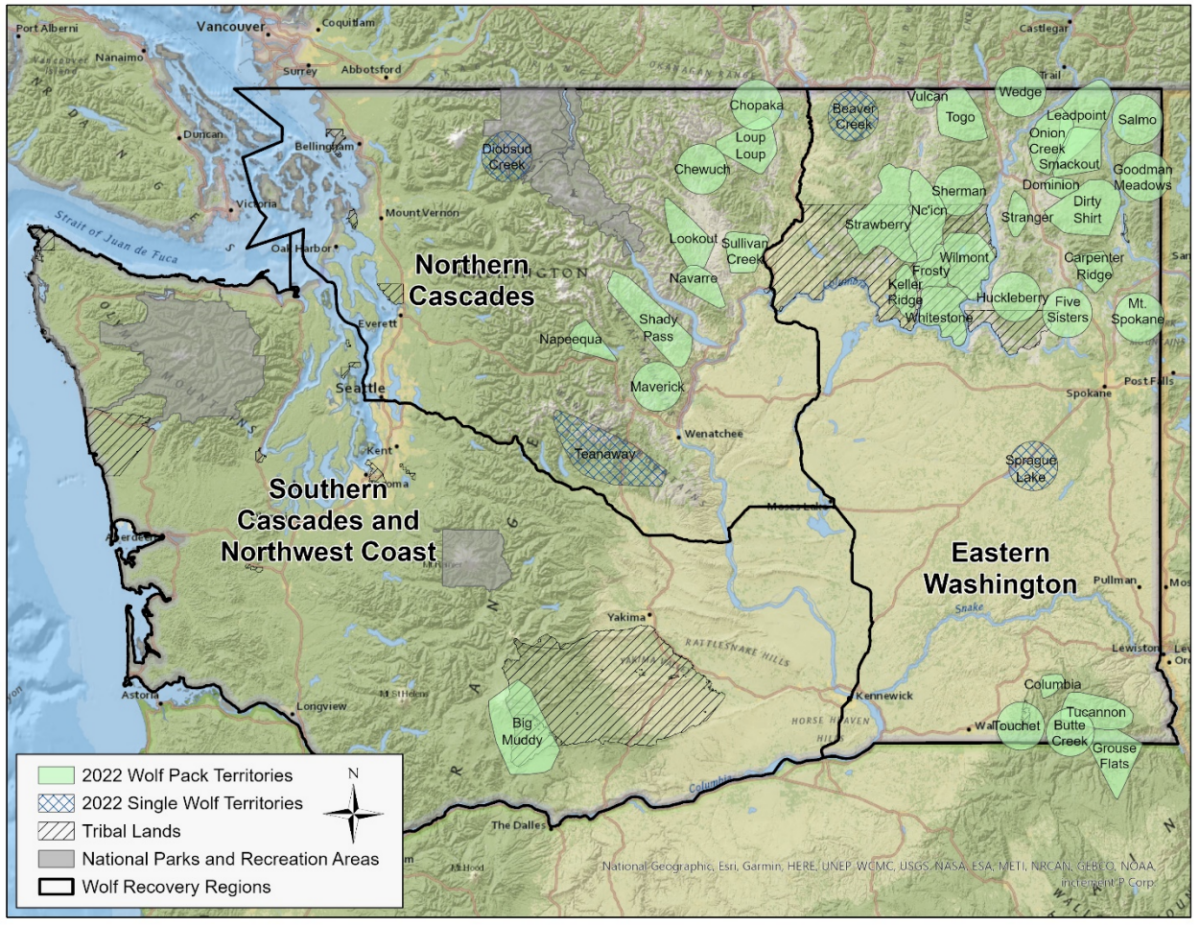

WDFW says there are eight new packs, including that first one in the South Cascades – Big Muddy in Klickitat County, named by the Yakama Nation – as well as Napeequa and Maverick in Chelan County, Chopaka and Chewuch in Okanogan County, Wilmont on the Colville Reservation in Ferry County, Five Sisters in Stevens County and Mt. Spokane in Spokane County.

“Most of the growth is in the North and South Cascades,” statewide wolf biologist Gabe Spence told the Fish and Wildlife Commission this afternoon during their meeting in Anacortes.

Two packs broke apart – Skookum and Nason – while Teanaway and Beaver Creek shrank to one animal apiece, below the definition of a pack, and the lone wolf of Marblemount continues to live a “hermit” life.

Overall, there were 141 wolves in the Eastern Washington Recovery Zone, 49 in the North Cascades Zone and two in the South Cascades and Northwest Coast Zone, plus another 24 lone wolves, mostly in that first zone.

It’s taken somewhat longer than originally believed for a pack to form in the greater Mts. Rainier-Adams-St. Helens area, holding up reaching statewide recovery goals – four successful breeding pairs in the three recovery regions plus three anywhere in the state for three straight years, or 18 in certain numbers in certain zones in a single year – and consideration of downlisting from state protections. The news of pack finally there will give Yakima and St. Helens elk herd hunters pause, while Conservation Northwest termed it “long-awaited great news and the best next step forward to achieving recovery goals.”

Spence said that for the ninth straight year the Eastern Washington zone has met its recovery goals of four successful breeding pairs and the Northern Cascades zone has now met it for three straight years.

While WDFW prepares a periodic status review, or PSR, a proposed budget proviso in the state legislature would require WDFW to complete a plan for establishing a procedure to manage wolves as if they were delisted from state endangered species protections when certain population benchmarks are reached in counties, an idea initially passed out of committee in February on a remarkable 11-0 bipartisan vote, killed by an expensive fiscal note, and then resurrected by House members late last month for final negotiations with the Senate.

The growth of Washington’s wolf population – documented through radio-collared animals, WDFW aerial surveys and other means – occurred even as 37 wolves were documented to have died last year (up from 30 in 2021), including 11 taken during tribal hunting seasons in Northeast Washington, nine poached (including six by poisoning) and under investigation, seven of natural causes – two by cougars, one by a moose, one by other wolves, two of old age, a pup from malnutrition – six lethally removed by WDFW in response to head off chronic livestock depredations and three justified caught-in-the-act shootings.

Speaking of, the agency reports 15 cattle – mostly calves – and two sheep were confirmed to have been killed by wolves in 2022, mostly on private lands, largely grazed pastures. WDFW reported only three packs were responsible for more than two confirmed depredations.

“We have a pretty low number of chronically depredating packs compared to other jurisdictions,” Trent Roussin, also a statewide wolf biologist, told the commission.

That’s become a mark of pride for WDFW, which spent a total of $1,632,569 was spent on wolf management in 2022, including $120,000 for lethal removals.

“Keep doing what you’re doing,” stated new Commissioner Steven Parker of Yakima, who expressed satisfaction with the money spent, though Commissioner Melanie Rowland of Twisp was less enthused.

All in all, the annual report provides a deep look into a flashpoint species that is clearly and long since been on its way.

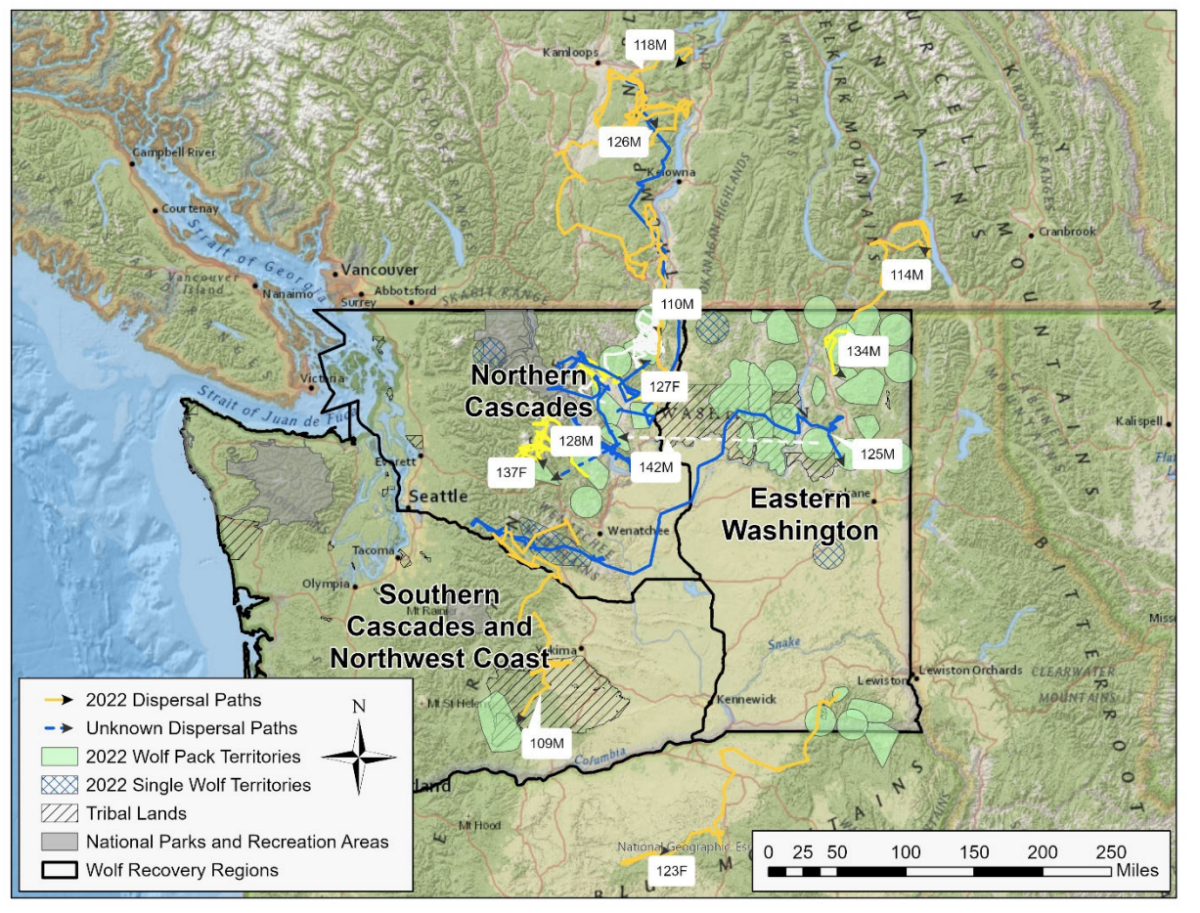

At least 12 wolves dispersed from their natal packs in 2022. A Loup Loup Pack wolf of Okanogan County helped form the Napeequa Pack of Chelan County with a Shady Pass Pack female. Three dispersed into British Columbia, one into Oregon. While a Teanaway Pack female moved northeast to the eastern side of the Spokane Reservation/southern Stevens County, a Spokane Reservation/southern Stevens County Huckleberry Pack wolf moved southwest and joined the Navarre Pack of the Okanogan-Chelan County line.

Where 109M, a male from the former Naneum Pack that crossed I-90 in late 2021, was confirmed to be traveling with another wolf at this exact same time last year, the sex of that other wolf wasn’t revealed till today. It is a female, confirmed through scat sampling done by University of Washington researcher Dr. Samuel Wasser and his lab, and together they form the Big Muddy Pack between the east side of Mt. Adams and Conboy Lake National Wildlife Refuge in the Trout Lake area.

Julia Smith, WDFW’s wolf policy advisor, called getting that pack there “a fundamental leap forward” towards reaching state recovery goals, and said that when the 2023 annual report comes out, it’s likely they will be a successful breeding pair.

While a 2016 prediction that said those goals could be reached as soon as 2021 has come and gone, an updated wolf population model from UW is expected to be released shortly.

“This year’s data shows that we’re really making significant progress,” Smith added.

New this year, WDFW is reporting areas of known wolf activity such as at the head of Lake Chelan, but notes that because they couldn’t count in the area during the winter survey, no animals are included in the annual tally. While that’s emblematic of the agency’s ready admission that the annual tally is a minimum, a lone wolf seen in the Sprague area during a flight was counted.

As for the impact of all those wolves on the state’s big game, that’s the subject of ongoing research in the Okanogan and Northeast Washington via WDFW’s and UW’s Predator-Prey Project. Initial results are beginning to be published and presented to the public.

Roussin says WDFW “hasn’t seen a huge impact” from wolves in those studies, adding that game harvest reports “don’t indicate major changes as well.”

Blue Mountains elk calf research has shown that it’s cougars that are the primary predators of young wapiti there, hampering that herds’ ability to rebuild itself.

Roussin also noted that Northeast Washington’s wolf population didn’t see a lot of growth over 2021.

Wolves were federally delisted in the eastern third of Washington and remain state-listed throughout.

Correction, 9:16 a.m., April 10, 2023: WDFW is performing a periodic status review, or PSR, of wolves in Washington, not a population status review, as originally stated.