WA Blue Mountains Elk Calf Numbers Lowest Since 2000

Elk calf numbers in Washington’s Blue Mountains continue to be well below levels needed to stabilize let alone rebuild this hard-bitten herd, according to a report out this morning.

Recent WDFW survey work yielded an estimate of just 17 young wapiti per 100 cows, the fewest since 2000 and among the five lowest marks all the way back to 1991, but also a not entirely unforeseen figure either.

“We expected it to be low based on high mortality rates on collared calves,” said Anis Aoude, agency Game Division manager.

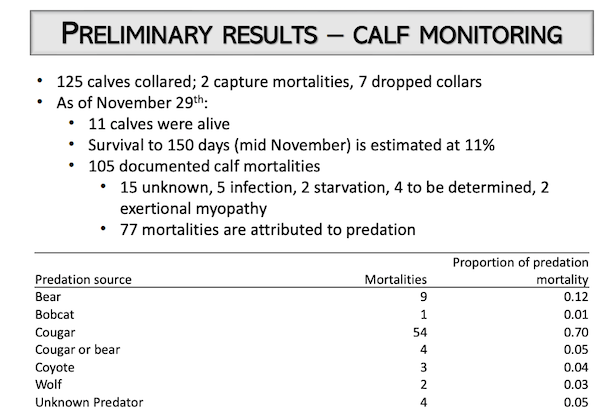

Just nine of 125 calves captured last May and outfitted with telemetry devices are known to still be alive, with seven out of every 10 of them killed by predators, mostly cougars but also bears, wolves, coyotes and even bobcats.

The annual postwinter survey did show an increase of 300 elk from 2021’s 30-plus-year low of 3,600, but that may have actually been due to better conditions when biologists took to the air to count the animals or more elk had moved across from Oregon at the time, the report cautioned.

It was published by Eric Barker of the Lewiston Tribune.

“I don’t think the difference of 300 elk between the two years is something that is significant, but the low calf ratio is significant and it does align with our collar data — which is two sources of data that say the same thing,” Paul Wik, WDFW’s district wildlife biologist, told the outdoor reporter.

Wik said that the calf-cow ratio “is below the level necessary to replace natural mortality or hunting” and that the biggest issue for the herd is young elk are just not making it to their first birthday in large enough numbers.

“A number in the 20s (per 100 cows) is probably a break-even number,” Aoude subsequently told this reporter. “You need something above that to start going back up.”

Aoude noted it was also a complex question with cow survival a key factor, and that the 17 calves per 100 calves was a midpoint in a confidence interval spectrum.

Barker reported that cow numbers are considered stable though yet to recover from the brutal winter of 2016-17. Drought conditions have also been an issue. But he wrote that bull ratios dipped to 20 per 100 cows, a mark below the last three surveys and five below the posthunting season goal of 25:100.

With the Blues elk herd well below its management objective of 5,500 and officially deemed “at risk,” earlier this month the Fish and Wildlife Commission adopted WDFW’s recommendation to cut two dozen any-bull and antlerless permits for the Blues, mostly on its east side.

But the citizen panel that oversees WDFW policy has been more loath to address predation, killing the limited-entry spring black bear hunt for 2022, which with its 158 tags could have at least helped disrupt bruin predation on elk neonates during May’s birth pulse.

One current member and another who resigned late last year suggested instead lowering the herd population objective and reducing hunting opportunities even further.

WDFW plans another round of calf captures this spring and will present rule-change proposals addressing the elk herd’s plight to the current commission in the coming months.