WDFW Recommends Denying Latest Wolf Rule Petition

WDFW says the Fish and Wildlife Commission should deny yet another petition that would more tightly shackle Washington wolf management, as well as reduce the ability of people to shoot wolves caught in the act of attacking their animals.

The nine members of the citizen panel will make the final decision on whether to proceed with 10 organizations’ requested new rulemaking at their critical late October meeting, but WDFW staffers posted their recommendation earlier this week, arguing that given 2011’s wolf plan and protocols that were subsequently developed with broad stakeholder input, “the complex issue of wolf-livestock conflict is best addressed not by codification of rules.”

Rather, the agency says the way forward is continuing with a slate of close working relations with local communities impacted by the recovery of wolves, building on ongoing collaborations, maintaining and expanding proactive deterrence programs and exploring new ways to reduce depredations.

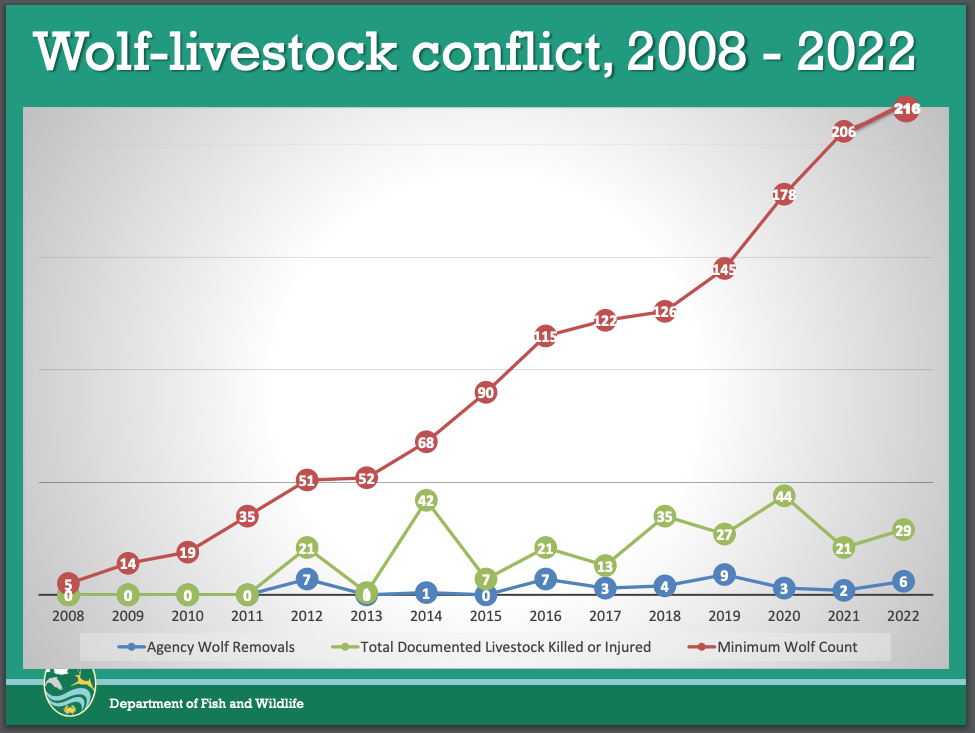

“Wolves are recovering in Washington. Our population has grown every year by every metric every year surveyed. We have the lowest levels of livestock depredation and wolf removals in the nation. Our wolf population continues to grow while livestock losses and wolf losses don’t. No evidence that a regulatory approach would result in better outcomes – in fact, there’s only evidence of the opposite,” WDFW states in a “bottom line” message to the commission.

This latest petition was initially filed this summer, then withdrawn, supposedly “to give the Commission more time to consider and discuss the petition before taking a vote,” and filed again by Washington Wildlife First, Center for Biological Diversity, Western Watersheds Project, Coexisting with Cougars in Klickitat County, WildEarth Guardians, Cascadia Wildlands, Northwest Animal Rights Network, Center for a Humane Economy, Kettle Range Conservation Group and Endangered Species Coalition.

It’s essentially a continuation of a now-decade-long push using the petition process, state courts, the court of public opinion and the Governor’s Office to force more restrictive rules on ranchers, WDFW managers and others in wolf country.

WDFW’s recommendation to the commission includes a lengthy timeline of all of that – petitions in 2013, 2014 and 2020, along with “several lawsuits” filed in state court from 2017 to 2020 that “were either dismissed or the court ruled in favor of WDFW,” according to the agency. “To date, none of WDFW’s lethal removal decisions have been found unlawful or improper in court.”

WDFW also outlined how much work went into answering that 2020 rule-making petition, which after the commission denied it, was appealed to Governor Inslee. He directed WDFW to come up with “clear and enforceable measures” around the use of range riders, nonlethal deterrent use, creating “action plans” in areas of chronic depredations, and more.

That led the agency to spend nearly two years and untold staff time and dollars on rulemaking – scoping parameters with the public, filing regulations, preparing environmental and small business impact statements, among other details shared in a timeline – all for the commission in the end to not adopt new rules, which would “chill the advancements we are making,” Chair Barbara Baker stated at the time.

The effect of the timelines is to show that WDFW’s successfully been around the block on this. The unstated message is that these petitions and lawsuits tie up a lot of resources. And to what end? Yet here we are again, with even more wolves in Washington and continued relatively few depredations compared to the rest of the West.

In this latest petition, the 10 groups want to require that all wolf depredations inside a 30-day window be confirmed (currently, one of three incidents can be probable) and have resulted in the deaths of at least two head before lethal action occurs; require ranchers to have used a minimum of two proactive deterrents; define exactly what range riding means; bar wolf removals on public land; limit kill orders to 30 days and only affect one wolf out of a pack; prevent removals near core wolf use areas and not if pups might be impacted; and require ranchers to have signed damage control prevention agreements before any wolves are killed on their behalf.

They also want to close caught-in-the-act provisions in state law to allow only livestock owners to shoot a wolf attacking their animal(s), and only if a depredation has already occurred in the area and only if the owner has a permit from WDFW’s director.

In explaining their rationale for denying all that, WDFW staffers point out that research has found “that people respond more favorably to conservation initiatives when the systems in which they operate recognize their autonomy, enhance and affirm their competencies, and create mutual respect and trust,” and that “Imposing a regulatory approach would likely undermine one-on-one relationships with local WDFW staff as well as acceptance and implementation of proactive, non-lethal tools by livestock producers who have been cooperating with WDFW on non-lethal conflict deterrence strategies.”

Part of their argument is linked to a 2021 paper that looked at Washington livestock operators’ perspectives around participating in conflict deterrence programs. “Barriers that hindered rancher participation [in nonlethal management strategies] included disdain for regulation both regarding the Endangered Species Act and the state’s requirements for accessing damage compensation, which were perceived to be extensive and over-reaching,” the authors wrote.

As for the reason not to codify wolf management rules, WDFW states wolf-livestock conflict is better handled by “allowing local WDFW staff to build one-on-one working relationships and trust with community members who live with wolves and are affected directly by wolf-livestock interactions and conflict” and “Continuing to build on years of collaborative process and relationship building through the Wolf Advisory Group to develop guidance from a broad spectrum of Washingtonians’ perspectives,” along with further work towards expanding proactive nonlethal deterrences and figuring out new programs along those lines.

As for amending the wolf caught-in-the-act rule, used on average slightly less than once a year in the nine years (there have been eight known instances of its use) since it was adopted by the commission in 2013, WDFW appears somewhat more amenable, but also states it has “concerns that if the rule is made too restrictive and does not reasonably allow for killing a wolf attacking livestock, working dogs, or pets, these actions would not be reported to WDFW for fear of criminal enforcement, increasing undocumented wolf mortality and impeding WDFW from tracking mortality sources and trends.”

One thing that’s perhaps particularly noteworthy in WDFW’s recommendation to deny is that it contains a pointed rebuttal of a recurring theme in the petition – that “taxpayer dollars,” “taxpayer funds” and “taxpayer money” is being used to kill problem wolves. All totaled, the ten orgs used the phrasing seven times.

“… (That) is not accurate,” the agency states. “WDFW maintains a separate account of funds from selling hunting and angling licenses that are used for a wide range of agency activities that includes lethal removal of wolves.”

An unrelated budget FAQ on WDFW’s website says much the same thing:

“Most expenses for wolves such as Damage Prevention Cooperative Agreements – Livestock (DPCA-L), Range Riders, and surveys are paid for through federal grants, personalized license plate sales, and the State General Fund. Funding derived from hunting pays for the wolf policy lead position which leads strategic planning efforts, development of new initiatives, fostering and development of partnerships, providing employee guidance, policy decision making, and recommending operations of staff. Finally, when mitigation strategies fail, recreational license revenue is used for the lethal removal of select wolves.”

At the risk of editorializing, as well as acknowledging that my tinfoil hat also just might be on too tight today, something is off about this latest petition. More to the point, it feels like it’s more about striking while the iron’s hot, per se, with a more predator-friendly commission since 2022’s 5-4 decision not to go through with Inslee’s requested rulemaking.

I think WDFW staffers lay out a pretty strong case for denying this petition. I don’t think Washington wolves’ verifiable recovery – one made without these restrictive rules in place, and while weathering lethal removals in response to livestock depredations as well as legal tribal hunting, poaching and more, all while contributing to wolf populations elsewhere – require them. That time – if it ever even existed in the first place, given the successful record and relative buy-in of ranchers on nonlethal strategies over the years – is well past.

And it’s past time for WDFW and the commission to spend another single minute on this.

And yet that’s what this game feels like it’s all about, getting the makeup of the commission to a point where it will pass. If I had a nickel to bet …