WA Lawmakers Hear About Wolves As Regional Delisting Bill Drops

They’ve long acknowledged them, but WDFW is now labelling two wolves in Washington’s Southern Cascades and Northwest Coast Recovery Zone a pack, a first for the region, and they’re working with the Yakama Nation to come up with a name for the duo.

The news came during a state House Agriculture and Natural Resources Committee workshop on wolf and cougar predation this morning. Last May, WDFW reported one of the wolves was a collared dispersing Naneum Pack male while the sex, age and origin of the other wasn’t known. Until now agency staffers had refrained from calling them a pack because a pack is defined as “two or more wolves traveling together in winter.” A Klickitat County producer today said their territory overlaps part of his ranch north of the town of White Salmon.

It also comes as a bipartisan group of legislators dropped a bill overnight that could conceivably delist the species in wolf-rich far Eastern Washington counties as early as 2024.

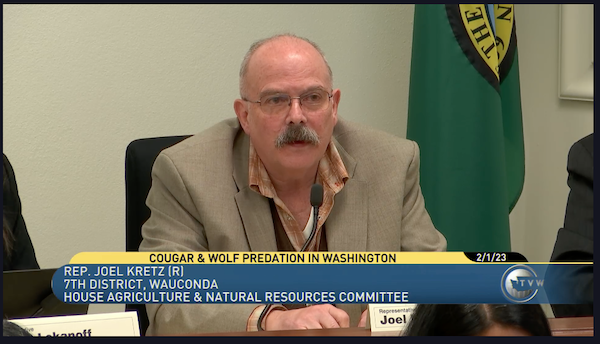

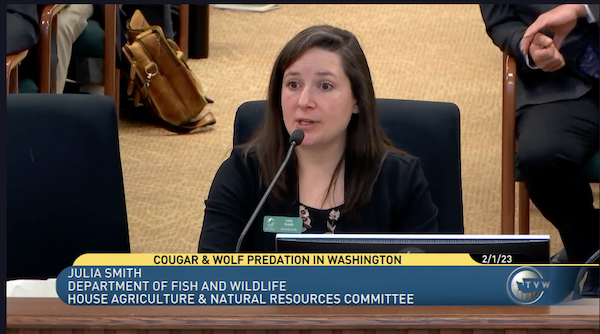

“Would the simple act of taking the state listing off these wolves imperil them in any way?” asked prime sponsor Rep. Joel Kretz (R-Bodie Mountain) of WDFW Wolf Policy Lead Julia Smith during the wolf workshop.

“Not in my opinion,” Smith replied.

In response to cosponsor Rep. Tom Dent (R-Moses Lake), who was puzzled about why wolves in the eastern third of Washington are federally delisted and not also state delisted, Smith stated, “Our state laws don’t allow for regional delisting.”

Enter House Bill 1698.

It would direct WDFW to manage gray wolves in certain counties as if they’d been removed from state endangered and threatened listings when: Washington as a whole has 15 or more breeding pairs for at least three years; there are at least three breeding pairs in that county; and the species is federally delisted there. The bill also would require counties to give WDFW and the Fish and Wildlife Commission a heads up that that threshold had been met and then enter agreements with the agency and local tribes to manage the species, in collaboration with local law enforcement.

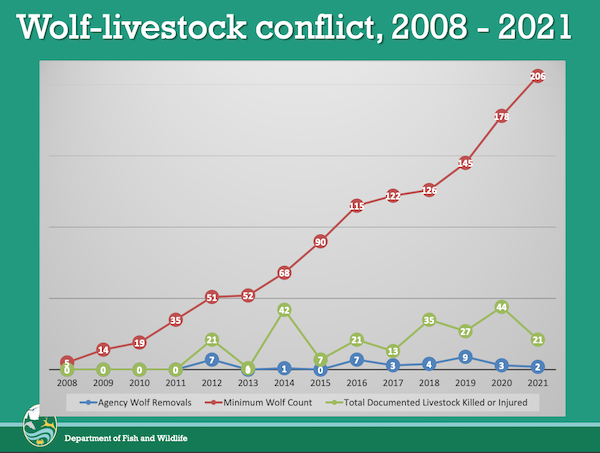

WDFW’s 2021 wolf report stated there were 15 breeding pairs in the state for the first time and it’s possible to probable that the 2022 report will find as many if not more, making it likely 2023’s report would as well, given the trajectory of wolf recovery in the state and 25 percent annual growth rates. There were a minimum of 206 wolves at the end of 2021. 2022’s annual report comes out in April.

Part of the frustration in far Eastern Washington is that the colonization of wolves across the state from source populations in British Columbia, North Idaho and Northwest Montana and from mid-1990s federal reintroductions in Central Idaho and Yellowstone National Park has and has not gone as expected.

At one point, WDFW forecasted that delisting goals – 15 breeding pairs spread across the three recovery regions in certain numbers for three straight years, or 18 in certain numbers in a single year – could be reached as early as 2021, but that hasn’t happened as packs have “bottlenecked” in Northeast Washington.

That region has “born the brunt of the good and bad” of wolf recovery, Kretz said. Over the years he has introduced a number of wolf bills, some less serious than others. This one’s bipartisanship collective is notable.

He added there needs to be “relief” for areas of the state that have recovered wolves.

Smith acknowledged that the bulk of Washington’s packs, some 66 percent, are in his neighborhood but also said colonization is in the range of what the Fish and Wildlife Commission’s wolf management plan – more than 11 years old now – anticipated.

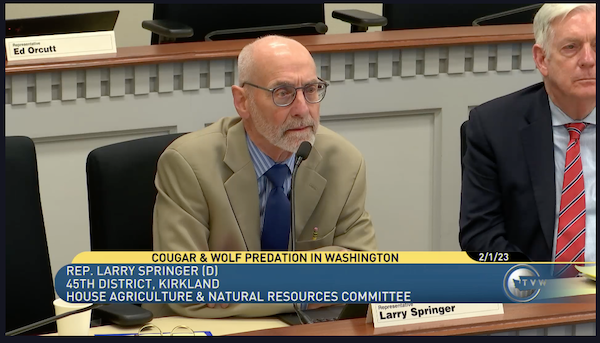

Asked by another bill cosponsor, Rep. Larry Springer (D-Kirkland), if WDFW is performing a status review for the species, Smith said that a draft was expected to be out in May, with the commission “ideally” making a decision on it this year.

Other lawmakers who put their name on HB 1698 include Rep. Mike Chapman (D-Port Angeles), who chairs the AGNR Committee; Rep. Debra Lekanof (D-Bow); and Rep. Jacquelin Maycumber (R-Republic).

Five of the six sponsors sit on AGNR, which is where the bill would likely be assigned for a public hearing.

To be clear, WDFW “hasn’t had time to really look through the bill or discuss” it, a spokeswoman stated early this afternoon.

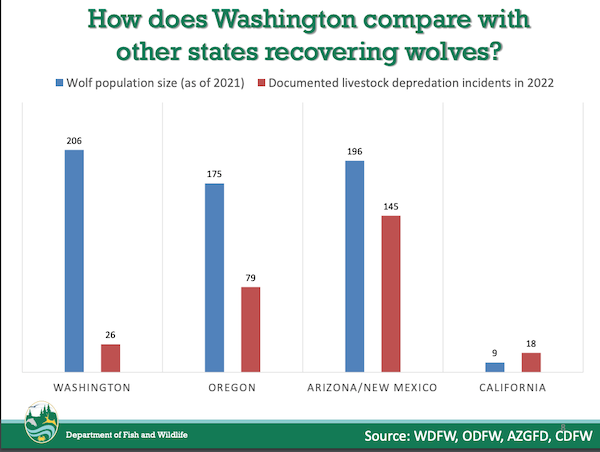

Back in the wolf-cougar predation workshop, Rep. Ed Orcutt (R-Kalama) asked about why Washington suffers relatively few livestock depredations compared to other Western states.

Smith said Washington invests an “incredible” amount – some 80 percent of WDFW’s wolf budget – on nonlethal measures, whereas places like Arizona and New Mexico apparently don’t but also tend to practice year-round grazing on national forests.

Speaking of public land, Smith wanted to correct a “misconception” around where cattle conflicts arise in Washington, stating that 23 of 2022’s 26 incidents occurred on private pastures.

WDFW Director Kelly Susewind said he thought that Washington wolves were also just better behaved, thanks to strong funding support from state lawmakers for nonlethal efforts that ranchers are “busting their rear ends” to put in place, making coexistence in wolf-cattle country somewhat easier.

Jay Shepherd, who operates a range-riding service in Northeast Washington called in from Colville to say that there was such a high demand for riders that he wasn’t able to fulfill all the requests and had to vet livestock operations by risk before assigning staff.

Rancher John Dawson of Stevens County, who said he runs cattle 50 percent on private land, 50 percent on public, stated that range-riding was “an important tool” but over time other tools have been taken out of the box and wolf-livestock conflict prevention protocols have been tweaked. He indicated that wolf depredations were cutting into his profits.

Asked by Rep. Chapman why wolves weren’t dispersing as well as expected, Smith said they were but also just filling in the best habitat first before setting up shop in less suitable areas. I-90 has likely been a barrier to movement into the South Cascades, where wolves are sure to find plenty of elk but also cattle and sheep operations. WDFW held a workshop entitled “Strategic Ranching on a Landscape with Wolves” in Goldendale, the seat of Klickitat County, in December.

Chapman also asked about the agency’s pack-naming protocols, to which Smith said typically biologists use a local geographic feature but in the case of the Klickitat wolves, WDFW was working the Yakama Nation to name the pack.

“The information on this pack will be officially released with the annual report, but there are two wolves there (as we have reported in monthly updates throughout 2022) and they’ll be officially named as a pack, and the pack named, in the annual report,” Smith said in an emailed statement to Northwest Sportsman late this morning.

WDFW’s Wolf Observations map shows at least two reports over the past six months of three wolves in the general area, including on a camera trap.

Rep. Kretz also wanted to know why there were so many packs on and around the Colville Reservation, where wolves are hunted year-round by tribal members (both on the reservation and the “North Half.”)

“Wolves can withstand a high level of mortality,” Smith stated.

WDFW’s last monthly wolf report, for December, said there had been 27 mortalities in 2022, a mix of agency lethal removals, poachers poisoning a pack, a number of other suspicious deaths, caught-in-the-act circumstances, tribal harvest, wolf-on-wolf and cougar-on-wolf battles, and natural causes, much of that in the wolfiest part of the state.

Wolf advocates continually push the narrative the state’s Canis lupus population is imperiled and WDFW’s management heavy-handed, requiring continued protections.