WA Coast Winter Steelhead Season Proposals Begin To Emerge

Washington steelhead managers laid out some initial proposals for the 2022-23 winter season on coastal rivers at a Zoom meeting this evening.

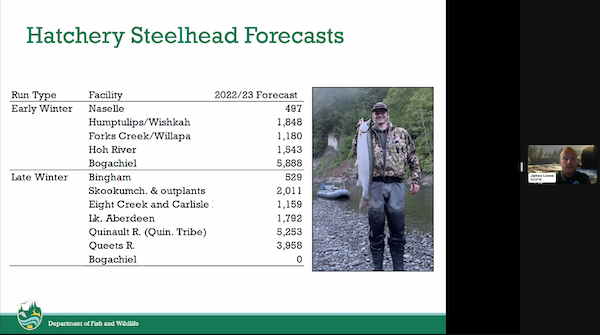

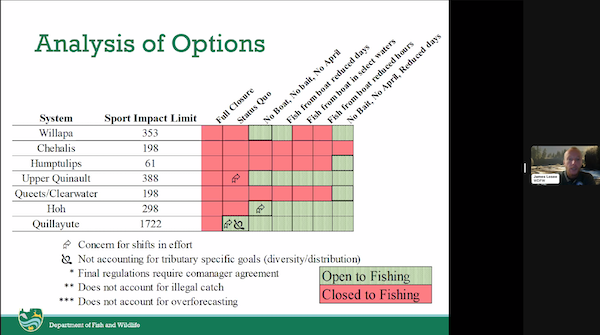

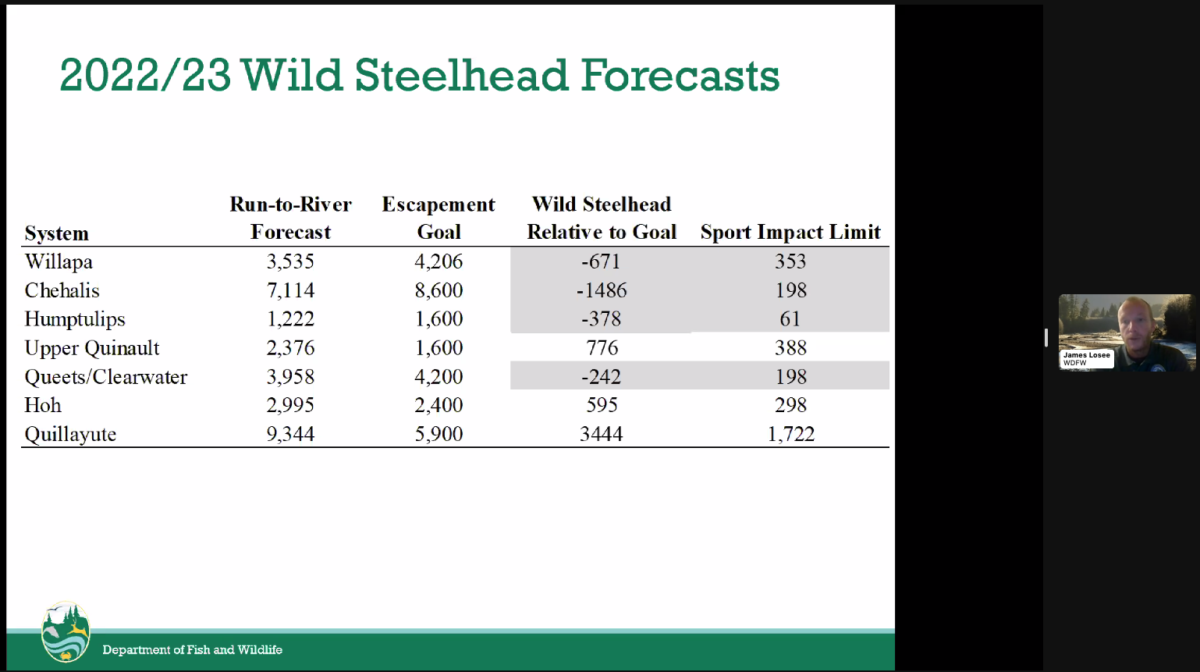

WDFW probably will again manage systems independently rather than use 2020-21’s blanket coastwide regs, with the most promising hatchery and wild opportunities likely on the Quillayute and Quinault Rivers, and in a change from last year, the agency is also at least exploring how to tap into late coho and healthy hatchery steelhead returns in systems otherwise expected to see poor wild winter-run returns.

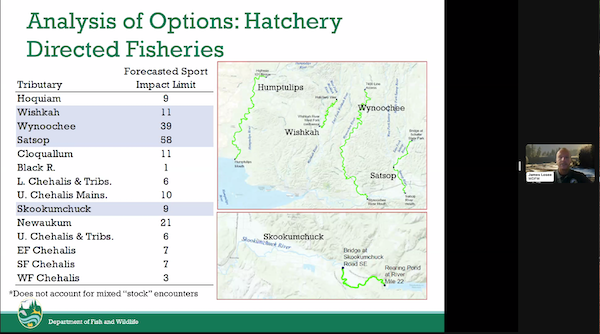

For instance, in the Grays Harbor watershed, the Chehalis and neighboring Humptulips are again forecast to be well below escapement goals, but there are late-running silvers on the Hump, Wishkah and Satsop and late-timed steelhead on the Skookumchuck and Wynoochee to be had and anglers want to get after them again.

Last winter all those rivers were entirely closed. In the case of the Skook, nearly 3,800 steelies ended up being surplussed to food banks and local lakes instead of fished for in the small river after late efforts to open it were rebuffed by WDFW because doing so wasn’t in the plan agreed to with tribal comanagers.

The message WDFW has received, according to regional fisheries manager James Losee, is that anglers don’t want to see fish surplussed; they want to see them in the creel.

So this year, Losee says staffers have “spent significant time and late nights” on the question of how to hold hatchery-directed fisheries.

It’ll be a trick because based on the preseason forecast, statewide steelhead management protocols limiting fishing impacts to 10 percent on underescapement runs, harvest sharing with the tribes and broodstock needs, in the Chehalis system there are only 198 sport wild winter steelhead mortalities available and just 61 for the Humptulips.

And that’s for all of the winter management period – December-April – across entire watersheds, so only really a handful of allowable dead fish per month in each river.

With such narrow margins, the answer might be a major ramp up in monitoring – “a creel like we’ve never seen in the coastal regions,” Losee told this evening’s audience.

Puget Sound and Columbia River anglers are no stranger to monitored fisheries. Clipboard-toting techs asking questions about catches, measuring their fish and cutting off salmon snouts are routine at boat ramps servicing fisheries held over ESA-listed stocks. (Coastal steelhead are unlisted so far, though the feds have been petitioned to list them.)

Losee imagined heavy monitoring with weekly updates and potential early closures when monthly impacts are met, with reopeners later on when more mortalities are available.

The rub: He only has four fisheries techs to work the banks and ramps and a biologist for crunching the numbers, which is probably not enough – at least in the beginning – to cover every one of the rivers anglers want to access again.

So part of tonight’s conversation was about prioritization: Which fisheries are most important to you, when?

I can’t say that I heard a lot of suggestions. When the question was posed to one longtime Skookumchuck angler, the gentleman balked, saying he didn’t want to take away opportunity from anglers elsewhere on the coast.

He did suggest that WDFW expand its potential Skook fishery downstream to Bucoda to prevent overcrowding on just the mile below the hatchery. He added that in 20 years of fishing the river he couldn’t recall ever catching a wild steelhead or seeing one landed either. (WDFW data shows 50 unclipped fish returned to the facility just below Skookumchuck Dam, with 43 released.)

Fisherman Brian McLachlan advocated for a risk-portfolio approach, taking higher risks where warranted, less in others.

To Losee it sounded like a proposal he said he’d received for portions of the Quillayute system, where Sol Duc wild steelhead are consistently doing well, those in the Bogachiel not so much.

Even as WDFW stretches to eke out fisheries where it can – regs complexity is more about trying to milk as much opportunity out of a less-than-ideal situation as possible – and liberalize where warranted, wild steelhead advocate Rich Simms warned about allowing too-effective means, which typically result in shorter seasons because impacts can be more rapidly eaten up.

When WDFW banned boat fishing on the coast in 2020-21, the steelhead catch dropped 50 percent or so.

Many anglers, including this one, and WDFW have pointed out that just as fishermen need steelhead, steelhead need anglers – to defend the fish and their habitat, to keep a pulse on the rivers and runs – and Simms noted that. But he added that anglers who care about the fish should also alter their own efforts to, in effect, make themselves less deadly.

Several callers either echoed him or called for a full closure. Julie Kelner said steelhead wouldn’t be forgotten if the waters were shut down a season.

John Davis said that if WDFW’s deal is to conserve fish, the Quinault and the Quillayute would be the only ones open, with the Bogachiel needing a deeper dive into its issues.

With the upper Quinault back in play, Brad Dailey called for status quo regulations, which would allow for boat fishing on this famed river.

You can send WDFW your ideas here.

Next up in the process is a Thursday, November 17, Fish and Wildlife Commission Fish Committee briefing that should flesh out WDFW’s direction a bit more, a meeting with comanagers to finalize management plans for the season, and a third virtual town hall late in the month to share recommended regulations that will be presented to Director Kelly Susewind for a final decision.

As if all that wasn’t enough coastal steelhead news for one day, this afternoon WDFW also dropped a weighty 138-page draft plan for implementing a legislative proviso wrapped around the fish and fisheries.

Public comment on the document bulging with information about the steelhead themselves, hatcheries and future hatchery management protocols, harvest, recent trends, watershed-by-watershed closeups and more runs through November 20 before a final document is presented to the state legislature in December ahead of next year’s long session.

“The Department feels it’s extremely important to include public feedback as part of this process,” said Kelly Cunningham, WDFW fish program director, in a press release today. “We encourage the public to dig in to the draft plan and share their perspectives with us so that we can incorporate their feedback as we finalize the report.”

WDFW estimates that implementing the proviso would cost $5.9 million every two years, “with most of this amount dedicated to freshwater sport fishery monitoring,” which happened to be a facet of this winter’s management that was stressed in tonight’s meeting.