USGS Maps More Washington Deer, Elk Herd Migration Corridors

New year, new maps showing important migratory corridors of Evergreen State big game animals – mule deer in the Central Washington and whitetails and elk in the northeast corner.

The cartography is part of federal, tribal and state wildlife managers’ continuing investigation into the seasonal movements of deer, elk and pronghorns across the increasingly developed and largely climactically bifurcated Western United States, with an aim to describe and protect these critical paths for our herds as they move from winter to summer range, as well as the forage-rich “stopover” points they hit in between.

“Many ungulate herds must migrate to thrive on the strongly seasonal landscapes of the American West. These corridor maps make it possible to plan for keeping those corridors open,” said Matthew Kauffman, a U.S. Geological Survey research wildlife biologist and lead author of Ungulate Migrations of the Western United States, Volume 3.

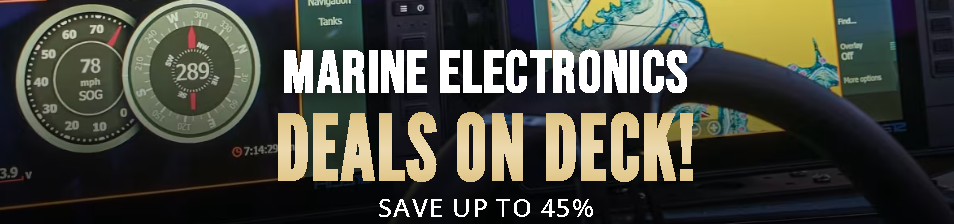

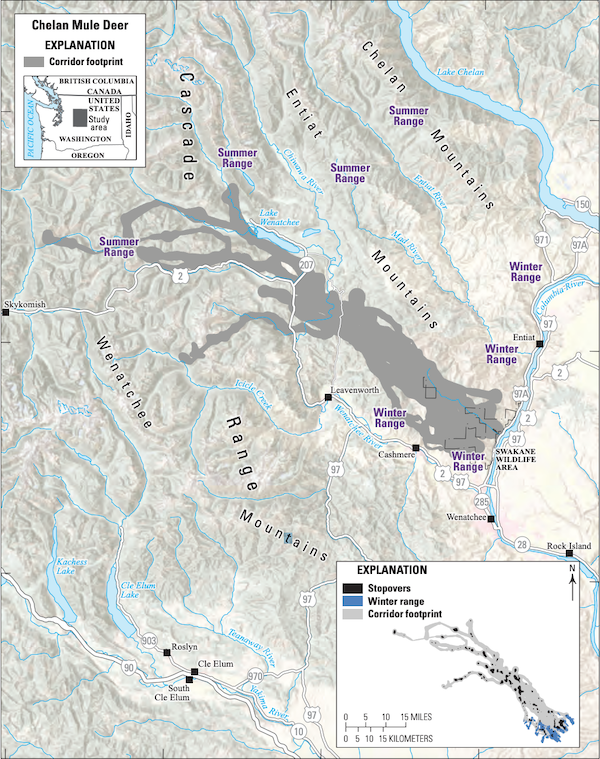

So far, animals from more than 150 herds have been collared for the ongoing project that began in 2018 and was authorized by a Department of the Interior Secretarial Order, and this latest edition looks at Chelan and Wenatchee Mountains mule deer, Selkirk whitetails and Pend Oreille elk, among others.

Late last summer, as I began to put together my annual Washington deer hunting prospects, WDFW biologist Emily Jeffreys shared with me some of the interesting initial findings from her district on the east slopes of the Cascades, including the fact that the muleys around Wenatchee represent two separate herds.

Of 19 does captured north of the apple capital on WDFW’s Swakane Wildlife Area and nearby Burch Mountain in January 2020, most moved into summer range between Lake Wenatchee and Stevens Pass – one or more actually summered west of the crest, not far north of the town of Skykomish – while those collared between Wenatchee and Cashmere utilized the Teanaway and other portions of the Alpine Lakes Wilderness in the upper Yakima River watershed in the high season.

Interestingly, the latter herd is considered to be part of the same population of mule deer that winter in Kittitas County along the southwestern face of the Colockum and in the Thorp area, which wasn’t well known before.

“Does in both subherds exhibited extremely high site fidelity, following their individual migration pathways very closely both within and between years,” Jeffreys told me.

Recent years have seen a fair amount of work to make US 97 more deer friendly as it slices through portions of Central Oregon and Northcentral Washington, and all of these greater Wenatchee-area subherds come in contact with the highway at some point in their annual movements. Mapping shows that where Swakane/Burch does tend to stay on the north side of US 2 the closer to Stevens Pass you get, two migration paths do cross the highway near Coles Corner to access the Chiwaukum Mountains and Icicle Ridge.

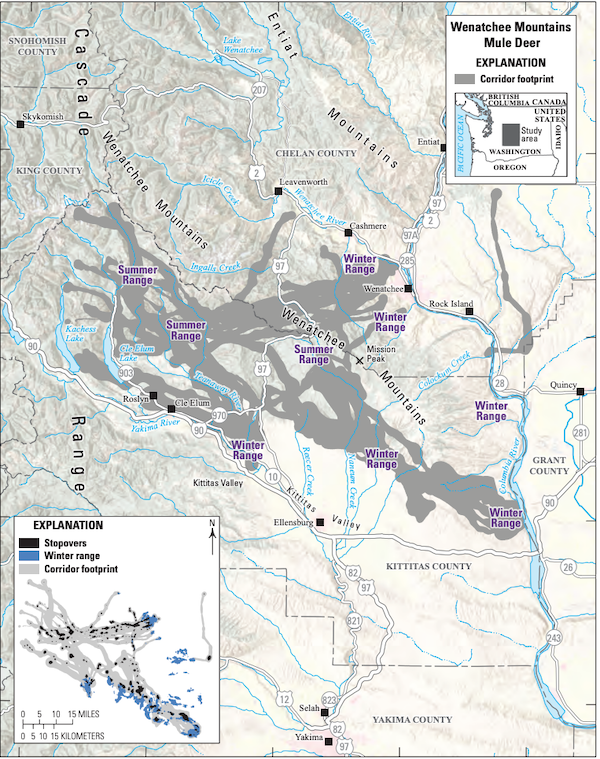

Whitetails aren’t thought of as being migratory like mule deer, but data from 126 Northeast Washington does shows some movement, albeit it lasting just under a week in spring and fall, with the latter migration occurring very late in the year. The mean move was 8.36 miles, with a maximum of 21.38 miles.

Where protecting and enhancing wildlife corridors is a major concern in Central Washington, there’s room for improvement in the range of Selkirk flagtails.

“This whitetailed deer population experiences some of the highest rates of deer-vehicle collisions in the state. Currently, there are no crossing mitigations in place along U.S. Highway 395 or State Route 20 to curtail collisions with wildlife,” the USGS report states.

Some local residents are more concerned about predators (a joint UW-WDFW study found the whitetail population is “declining a little bit”), but nearly all of Highway 20 from Colville to Tiger is part of a whitetail corridor to summer range. While much of that is considered low use, the route does cut through parts of at least six identified stopovers – places where migrating ungulates typically can find richer forage and stay a few days to replenish themselves.

Volume 3 follows on the 2020 publication of Volume 1 and early 2022’s Volume 2, which looked the Okanogan’s important Methow mule deer herd. So far among the three Northwest states, Idaho big game populations have been mapped the most. WDFW biologist Stefanie Bergh late last summer told me that studies began on Southcentral Washington’s Klickitat County mule deer herd in early 2021; at the time she wasn’t expecting to see as much migratory movement as fellow agency bios well to her north do.

“When the first sets of maps came out, we were excited about how these maps could be used for conservation planning, but that was mostly aspirational,” said Kauffman, the federal author, in a press release. “Now in Volume 3, we have examples of how migration maps are being used on the ground.”

USGS says they’re being used “to plan and construct wildlife underpasses and overpasses that allow animals to safely cross major highways or to develop message boards and automatic systems along highways to alert drivers of crossing animals. Maps are also being used to remove fences, inform recreation planning, guide siting of renewable energy projects, and limit housing development in migration corridors through zoning and conservation easements.”