WASHINGTON’S HARVEST HIT A NEW LOW MARK IN 2021, BUT THERE ARE GOOD SIGNS IN SOME HUNTING DISTRICTS THIS FALL.

By Andy Walgamott

The good news about a season like Washington’s 2021 deer hunt is that it only comes around so often, and with that wreckage in the rearview mirror – albeit still smoking somewhat – there are some things to look forward to this fall.

For starters, there’s absolutely nowhere to go but up (author knocks on wood, crosses all fingers and toes, rubs lucky wolf’s foot) after the Evergreen State’s lowest general-season harvest this entire millennium, just 22,881 bucks and does (24,318 deer when special permits are included), a total that was down 4,800 deer from 2020.

No doubt an increasing predator guild is eating good in Bambi’s neighborhood, but last year’s nadir was actually largely fueled by big disease dieoffs that struck all three huntable species and dealt particularly harsh blows in two key hunting districts, the Palouse and Northeast Washington. They saw combined general and permit harvest drops of 2,300 and 850 deer, respectively.

But some 9,350 fewer riflemen, archers and muzzleloaders also hit the woods and fields last year. Whether it was 2020’s pandemic bump in hunter numbers calling in sick or sportsmen heeding the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife’s warning that 2021’s whitetail outbreak was bigger than 2015’s and so they stayed home instead, or a bit of both, that likely played a role in the decline too.

For example, even as I rail at deer camp about all the other $%@$%@# pumpkins on the mountain, I also know I need some extra folks out there just to stir up the bucks and send ’em toward my lair in the patch.

To help rebuild those hemorrhagic-disease-hit herds, WDFW has tweaked this year’s regulations a bit, moves that will continue to dampen harvest in the short term but benefit it in the future.

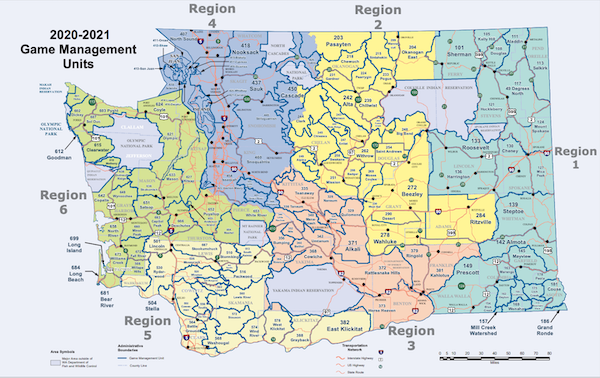

“In those impacted areas, mostly in Region 1 but also in Region 2, the Department reduced special permit opportunity for 2022, primarily to reduce mortality of antlerless deer and promote population recovery,” Kyle Garrison, the agency’s ungulate specialist, tells me. “With the reduction in antlerless harvest and a spring/summer with favorable conditions, we’re optimistic we’ll see populations rebound quickly. That said, we anticipate another year of overall depressed harvest due to the impacts of 2021’s outbreaks.”

Bottom line is that it’s going to take a couple years to rebuild flagtail numbers across the eastern tier of the state.

TL;DR Version Of The Following 5,600-plus Words

“Generally speaking, whitetail deer hunters can expect tougher hunting than average due to reduced populations, especially in the Palouse, Blue Mountains and Selkirk Management Zones. Mule deer hunters shouldn’t expect too much deviation from last year – harvest was depressed in 2021 in several management zones but not to the extent of whitetail deer, likely a reflection of less severe impacts of hemorrhagic disease. Hunters pursuing ghosts of the forest, aka blacktail deer, can expect normal hunting prospects. The majority of management zones exhibit stable harvest trends, which indicate population stability.”

–Kyle Garrison, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife ungulate specialist

But the region’s mule deer weren’t hit as hard and their populations are generally stable. What’s more, herds of the big-eared bounders in portions of Central Washington have bounced back from a tough winter some years ago and they came out of last fall with some pretty promising buck-to-doe ratios, including, surprisingly, in the wide-open counties of Adams, Douglas and Grant. And herds in Chelan, Klickitat and Okanogan Counties aren’t in bad shape either.

On the Westside, I’d put a nickel down that we’re building toward a very solid blacktail harvest, the kind that comes around every half dozen years or so. Even though some areas can suffer winter loss, recent snow seasons should not have affected this fall’s crop of bucks.

The caveat that’s keeping me from putting even bigger money on 2022 is one coastal biologist’s theory that last year’s extreme heat may have elevated fawn mortalities among the young bucks set to power this season’s harvest. We’ll see how that plays out.

While the general early archery deer season began September 1, this Saturday, September 24, marks the start of muzzleloader hunting across the state and, as always, the first Saturday in October after the 10th – this year that falls on October 15 – will find rifle hunters heading afield.

In the here and now, Washington deer chasers looking for tidbits about this season should read on.

“For pointers, I would really lean on the hunting prospects,” tips Garrison. “Our biologists put a lot of work into summarizing all available information – most importantly, that ‘on the ground’ knowledge – to help hunters find success in the field.”

The following is an amalgamation of what those district biologists tell me and what they published in their annual fall hunting forecasts.

NORTHEAST WASHINGTON

It wasn’t a big surprise that last year’s deer harvest took a dip in the state’s upper righthand corner, given the big disease dieoff before and during the season, but the effects are going to linger into this fall.

“As expected, because of the large-scale bluetongue/epizootic hemorrhagic disease outbreak last summer, the deer harvest will likely be down again this year,” wildlife biologist Annemarie Prince in Colville tells me. “I’m thinking probably close to last year’s harvest. We seem to be seeing good fawn numbers, but those fawns will need to make it through winter before we’ll see them contributing to the population. So I don’t think we’ll see that bounceback this season, but hopefully with a mild winter, we’ll see it start to come back in the 2023 season.”

CHRONIC WASTING DISEASE MONITORING INCREASED

Even before last fall’s discovery of chronic wasting disease in four Idaho deer and an elk not far from the tristate border, Washington wildlife managers stepped up monitoring for the always-fatal condition, boosting the number of game check stations in the state’s northeast units and asking roadkill salvagers there to get their deer and elk tested too.

This year, that surveillance effort has been expanded to cover all of Region 1, from the Canadian border to Boggan’s and westward into the Columbia Basin.

“This means we are focusing our sampling efforts throughout this region, which includes operating additional hunter check stations in Southeastern Washington near the detection in Idaho,” Dr. Melia DeVivo, a WDFW ungulate research scientist, tells me.

To be clear, there have been no known cases of CWD in the Evergreen State, but the infected Idaho animals came from the White Bird area south of Lewiston, only 40 air miles from where Washington, Idaho and Oregon come together, and there’s another cluster of whitetail cases in Libby, Montana, 70 miles as the crow flies from Newport.

New check station locations this year include Republic, Washtucna, Burbank, Walla Walla and Clarkston. It’s crucial to stop by, as early detection will allow for a more rapid response and, hopefully, containment. A University of Wyoming study DeVivo worked on estimated CWD shrank the size of one deer herd by 19 percent annually and that in 41 years the population would go extinct.

Forty-one years is within the career of a deer hunter.

“We have also expanded our efforts to include adult elk and adult mule deer,” DeVivo adds. “So we are now collecting samples from any adult deer or elk in Region 1. We will continue to collect samples statewide of any cervid that presents with suspicious signs of CWD.”

And there are new rules for bringing moose, elk, deer and caribou into Washington from anywhere, not just CWD states and provinces.

“This update helps protect our state’s cervids even better from inadvertently transporting high-risk parts such as brain and spinal cord into our state and potentially infecting other animals,” DeVivo explains. “Prior to this update, caribou were not on the list even though they are known to be infected and the rule only applied to places that have already detected CWD, which relied on other states and provinces to first detect CWD in their cervid populations. This was a reactive response rather than a proactive process, which it is now.”

For much more, see wdfw.wa.gov/species-habitats/diseases/chronic-wasting/surveillance-program.

Prince’s official forecast is for a “below-average” harvest because two of the state’s perennial-best game management units for deer, Huckleberry and 49 Degrees North, were among the hardest hit by the two outbreaks, which are transmitted by gnats that occur around water sources in dry, hot summers and falls.

The 2021 season saw the lowest general rifle and overall general-season harvests – 2,835 and 3,544 – in WDFW’s District 1 in at least the last nine years, and by a wide margin. Another measure of how rough a season it was is that it took riflemen 24 days on average to harvest a deer, twice as long as 2015. To be fair, 2015 was an exceptional modern-day year here and across the state, but it’s still at least three to four more days on average than recent seasons.

Because the diseases hit bucks, does and fawns alike and does are the largest population in the herd, as well as its reproductive engine, it may take a few years for the population to rebuild. There are no antlerless permits for the region and no opportunities for youths, let alone senior or disabled hunters, to take a doe, except in the Mt. Spokane Unit.

Then there are the furry fangers. This is the state’s wolfiest country, and they’re just as hungry as cougars, coyotes, bears and bobcats. At an early August Fish and Wildlife Commission meeting, public officials from Northeast Washington spoke to high predator populations and low deer numbers. Stevens County Commissioner Wes McCart said he had seen just one deer on his 170 acres this year, while in past years the tally was more like 300 or 400.

“We acknowledge that carnivores have some impact on ungulates,” Staci Lehman, a WDFW spokeswoman in Spokane, tells me, “and combined with all the other factors, it can add up to a drop in population numbers in some years, depending on what else is happening.”

Some of “the other factors” she points to include the aforementioned disease issues, plus wildfire and drought.

And then there’s habitat loss; this landscape just isn’t what it was in the 1980s for whitetails as old farms and forests are converted to development or go out of production.

“I also always try to reference collisions with automobiles,” Lehman adds, “because people don’t realize just how many deer are hit by cars.”

In the meanwhile, longterm days-per-kill data shows a mix of trends for the district’s units, from some beginning to require more time to bag a deer (Sherman, Aladdin, Selkirk) to others being essentially stable (Kelly Hill, Douglas, 49 Degrees North and Huckleberry). Something to track.

“Vegetation is still pretty green at the higher elevations,” bio Prince told me in late August, “but this heat has dried stuff up in the lower elevations. Despite that, I think deer harvested should be in good shape.”

PALOUSE AND SCABLANDS

The greater Palouse has zero wolves (or at least very few of them) but all of the Northeast’s disease issues, and then some. Indeed, it was the epicenter for EHD and bluetongue, and unsurprisingly last fall saw a very sharp harvest dropoff from Mt. Spokane to the Snake and westwards into the upper Channelled Scablands.

General rifle and overall general season takes plummeted to 1,864 and 2,568, respectively, from 3,124 and 4,545 in 2020. Significantly more days were needed to harvest a deer – 20 percent more for multiweapons, 40 percent for bowmen, 50 percent for riflemen, 79 percent for smokepolers.

“If we get more wet springs and mild summers, like this year has been so far, then they will bounce back here in a couple years,” Michael Atamian, district biologist, tells me. “But if we get more drought and heat waves or hard winters, it will take longer for them to recover.”

Last year’s suspension of general-season antlerless whitetail opportunity for all archery, muzzleloader, senior and disabled hunters continues this season “to reduce pressure on the does and let the population rebound a bit faster,” he states.

“Mule deer is a bit of a different story,” Atamian adds. “They are more resistant to EHD than whitetails and the postseason aerial survey population estimate was in line with previous years. However, fawn numbers were down, likely due to the severe drought reducing fawn survival. So buck numbers should be decent this year, but come 2023, when those 2021 fawns would have been coming of age (growing a third point), there likely will be a bit fewer to choose from.”

His district prospects can be found here.

The district is pretty light on public lands and unfortunately a good-sized chunk of one of its bigger sections, the Revere Wildlife Area southwest of St. John, burned in mid-August, Atamian points out. Best bet is to bone up on WDFW’s Private Lands Hunting Access Program (privatelands.wdfw.wa.gov). Some 146,000 acres of the region were enrolled in it as of this July, ranging from Feel Free To Hunt to Hunt By Written Permission and Hunt By Reservation farm, range and bottomlands.

BLUE MOUNTAINS

General deer harvest in the state’s southeast corner may tick back up “marginally” this fall, but it will also be doing so from a nine-year low. This district too was bitten by bluetongue and EHD, with normally resistant mule deer also succumbing. Biologist Paul Wik tells me 15 percent of 40 collared does in Walla Walla, Columbia and Garfield Counties died.

It’s the latest in a series of setbacks for muleys and whitetails in these parts, including a pair of tough winters, that has dragged general rifle and overall general harvests down from 2,471 and 2,956 deer, respectively, in 2013 to 1,393 and 1,797 last year.

Loss of winter range in recent years due to lower Conservation Reserve Program enrollments is a cause of concern, but fires in the heart of the Blues – the Wenaha-Tucannon Wilderness and Lick Creek on the range’s eastern side – should benefit deer on their summer range, Wik reports.

“With back-to-back average to mild winters over 2019-22, we had been expecting to see improvements in deer populations across the district; however, drought conditions and hemorrhagic disease last year took a toll on some portions of the deer herd. The district saw increases in the number of days it took hunters to harvest a deer in almost all GMUs, with only the mountain GMUs showing stable or modest [harvest per unit effort] decreases, but this is likely due to lower hunter numbers,” Wik wrote in his hunting prospects. “Despite the effects of drought, fire and disease last season, we expect overwinter survival was very good, and are expecting deer harvest to marginally improve through the 2022 hunting season.”

If you can muddle through this fall, that “very good” winter survival could translate into better hunting next year, as most of last year’s class of fawns become legal bucks, Wik tells me.

The best GMUs in terms of harvest and fewest days needed per kill are typically the ag-heavy, largely private units rimming the Blues – Prescott, Mayview and Peola – but tiny Grande Ronde, shimmed into the extreme southeast corner of the state south of the eponymous river and hosting a lot of public land, compares pretty well, at least in terms of days per buck – 15 last year.

OKANOGAN

Not to draw too much attention to where I’ve enjoyed deer hunting going back to the early 1990s, but Okanogan County escaped the worst of 2021’s disease outbreaks and managed to pull off a slightly above-average harvest of 2,228 deer, 1,487 of those by riflemen. (In case you’re wondering, yours truly enjoyed a lovely tag taco). District biologist Scott Fitkin tells me this fall’s kill will be “similar to last year.”

“Improving postseason fawn:doe ratios and probable higher-than-average estimated fawn recruitment in 2021 likely means a modest increase in 2.5-year-old buck availability in 2022,” he writes in his season forecast. “Last December’s observed mule deer buck:doe ratio of 20:100 indicates average buck carryover from last season. Total general season harvest and success rates are anticipated to be around the five-year average.”

For the record, that mean kill mark is 2,113 deer (mostly bucks) for all weapons categories, and looking at the longer term trend, harvest the past two years show that mule deer and whitetail herds are working back toward the levels seen right before those three big years in the mid-2010s, when we took from 2,700 to 3,600 deer.

On the one hand it makes sense that the district’s biggest unit, Okanogan East, serves up the largest harvest – an even 700 for all weapons types last year – but it’s also a function of a pretty good mix of private, state and federal lands, agriculture and timber, mule deer and whitetail. Just west of the Okanogan River, the Sinlahekin, Wannacut and Pogue Units offer a similar scenario, then it grades more heavily into muleys and mostly public land to the west.

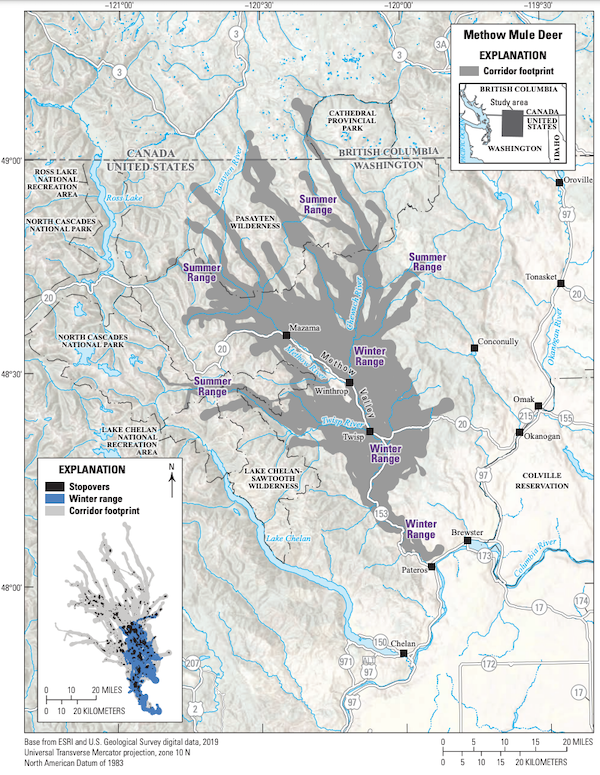

Speaking of, these deer roam and the U.S. Geological Survey’s Ungulate Migrations of the Western United States, Volume 2, published earlier this year, provides some interesting details about the herd. Based on 128 radio-collared does, it found that the median start date for the fall movement to winter range was October 14 to 23 – which almost perfectly overlaps typical general rifle dates – and the animals spend a mean of 14 days on the trail, covering an average of 29 miles but as much as 65 miles as they descend from the Pasayten, Cascade Crest, Sawtooth Divide, the Tiffanies, even British Columbia’s Cathedral Park, to the Methow Valley.

Bucks will be found in the heights and in the myriad regenerating burn scars until forage availability and snows drive them down toward the winter range. But the in-between ground always holds antlered muleys, and they’re not just 2½-year-old three-by-twos.

CHELAN-DOUGLAS

Deer herds and harvest have recovered in WDFW’s Wenatchee District from the harsh winter of 2016-17 and there’s no sign that this fall will see a reversal of that trend. The 2021 posthunt Chelan County buck-to-doe ratio was 24:100 and the fawn-to-doe count was 76:100, good news for this fall and next season west of the Upper Columbia. On the east side of the big river in Douglas Conty, the sex ratio was even better, 26 bucks per 100 does, well above the management goal of 15-19:100 for this generally open landscape.

“I do expect to see more hunters and greater harvest this fall in Chelan County and Douglas County than last year, but likely not quite as high as was experienced in 2020,” Emily Jeffries, the district biologist, tells me.

Perhaps buoyed by the pandemic, two falls ago saw general rifle and overall general harvests in both counties bump up to 1,387 and 1,876 deer, respectively, high marks back to 2015’s great season. Last year’s take was 1,198 and 1,800, perhaps more reflective of lower hunter numbers than a dropoff in deer numbers, as days per kill didn’t vary that much.

“The Entiat Unit in Chelan County and the Big Bend Unit in Douglas County once again produced the most harvest of the District 7 GMUs in 2021,” Jeffries reported in her season prospects. “Of these two units, the productivity of Big Bend is perhaps more notable, as it routinely attracts significantly fewer hunters each year than several of the Chelan GMUs, yet outpaces these in harvest.”

Big Bend is capped by a remote but sprawling state wildlife area that some hunters boat into via the Columbia, while other public lands are sprinkled throughout the unit. In fact, for a primarily agricultural landscape, Douglas County as a whole hosts more than its fair share of federal and state lands. And between it and Chelan County, things don’t look half bad.

“Given the mild winter, the cold, wet spring that marked the end of drought conditions, and lack of known disease events, biologists have no reason to believe that the 2022 deer harvest will continue last year’s decline,” states Jeffries about her district’s prospects.

Thanks to funding from the Department of the Interior to study migratory Western deer, she is also learning “interesting” things about Chelan County’s herd. In January 2020, does on two winter ranges along the Columbia were collared and that data has since been crunched.

“For one, the mule deer that winter in the Wenatchee Foothills south of Highway 2 and north of I-90 represent one population,” she tells me. “Approximately 90 percent of the does collared in the Chelan County portion of this Wenatchee Mountains subherd are migratory and spend their summers in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness west of U.S. 97 and south of Highway 2. The does collared in the Burch Mountain/Swakane area – part of the Chelan subherd, which extends from Highway 2 north to the south shore of Lake Chelan – are also primarily migratory, traveling west into higher elevations each spring.”

“For both subherds, the duration of fall migration averages about three weeks, with a median start date of October 25 and most deer arriving on winter range by mid-November. The average migration distance for does in both subherds was around 25 miles, but individuals traveled as few as 5.8 and as many as 50 miles. Does in both subherds exhibited extremely high site fidelity, following their individual migration pathways very closely both within and between years.”

That’s all well and good, and represents information that surely will help land, wildlife and transportation managers do a better job, but what can you tell us about those does’ boyfriends, Emily?

“While only does were collared as part of this study and buck migratory behavior differs, there is enough overlap between the sexes that we can use these findings to surmise broad generalizations on where hunters should focus their efforts,” Jeffries tells me. “For instance, these findings suggest that in Chelan County, hunters will typically benefit from focusing on midelevation transitional range by the modern firearm season, while hunters may have better luck on low-elevation winter range closer to the banks of the Columbia by late archery season. Conversely, early archery, High Buck and even early muzzleloader hunters should focus on high-elevation summer range.”

“It’s important to note that these are general suggestions only, though,” she adds, “as fall mule deer migration is heavily influenced by snowfall and timing can vary from year to year depending on the weather. One key difference to note between the sexes is that does typically choose to migrate through and winter in areas with the highest quality forage, regardless of proximity to roads and neighborhoods, while bucks – especially older age-classes – will stick to areas farther away from roads.”

COLUMBIA BASIN

As with Douglas County to the northwest, Beezley and Ritzville buck numbers after last season were higher than you’d expect for such expansive country – 28:100 and 23:100. The two most hunted units in the Columbia Basin also saw “good” fawn-to-doe ratios (52 and 48) last year, per biologist Sean Dougherty, leading him to forecast “another good year for mule deer hunting throughout the district.”

There’s more public land in this ag-rich region than there is to the east in the Palouse, and some WDFW wildlife areas are rated as fair to good for deer hunting (Lower Crab Creek and Sun Lakes in the former category, Banks Lake in the latter). There’s also 179,000 acres of private lands enrolled in the agency’s various access programs, largely Hunt By Written Permission ground in Adams County.

To the south, Kahlotus Unit biologist Jason Fidorra reports 19 bucks:100 does coming out of last season, a mark that’s within management goals, but below-average fawn numbers (58:100), probably due to drought last year. With its mostly migratory herd, it’s a unit to keep your eye on if 1) you have a muzzleloader or multiseason tag, 2) an early winter has hit the upper Columbia Basin and 3) you’d prefer to spend Black Friday hunting instead of shopping.

SOUTHCENTRAL

Deer harvest in Yakima and Kittitas Counties continues to slink along at low levels. By and large the duo see some of the lowest success percentages in the state, just 2 or 3 percent in several units west of the city of Yakima, and 7 percent overall (the statewide average is 23 percent). But on the bright side, at least you won’t have a lot of competition!

“The 2022 harvest is hard to predict,” states district biologist Jeff Bernatowicz in his forecast. “Last winter was harder than most, but mortality on radio-collared deer from starvation was not high.”

Preliminary results from Muckleshoot Indian Tribe collar studies suggest that cougar predation and nutritional stress are impacting the local herd.

Best advice here is probably to avoid the main elk units and hit the Teanaway. It’s the district’s best in terms of deer harvest and success percentage (12 percent over the past three years on average), features plentiful public land and is known for producing bruisers from time to time.

COLUMBIA GORGE

The Columbia Gorge was one of the regions of the state that held the line during last year’s overall poor showing, with kill here relatively stable compared to 2020, and there are decent signs for 2022’s hunt.

“We did hold steady last fall and I expect that harvest will be similar this coming fall. I am crossing my fingers that maybe it will even be a little bit better!” district biologist Stefanie Bergh tells me. “The deer seemed to have survived that bizarre April snowstorm and the wet spring contributed to good forage conditions into the summer. We have mule deer in 388 and 382 that are radio-collared as part of the Secretarial Order 3362 migration and winter range project and they have had higher survival in 2022 than during the same time in 2021.”

We’ll get to that migration study in a bit, but there has been a touch of AHD, or adenovirus hemorrhagic disease, reported in the Goldendale area, where the fatal condition was first confirmed in Washington back in 2017. In late August, Bergh said 18 deer were known to have succumbed, with other unreported mortalities likely.

As is typical for this country in late summer, a number of local timberland owners had closed their properties to public access due to high fire danger, Bergh points out, so check ahead.

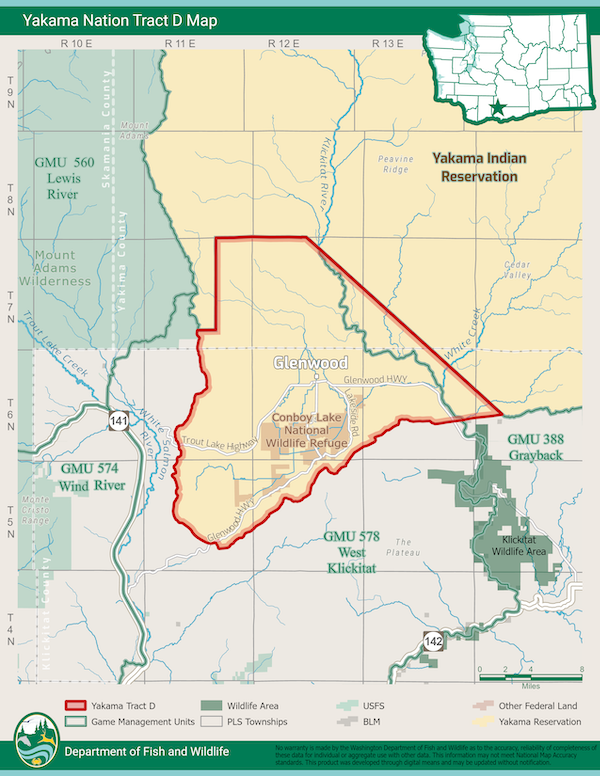

And if you hunt in the vicinity of Glenwood and Conboy Lake National Wildlife Refuge in the West Klickitat and Grayback Units, following a recent federal court ruling this area known as Tract D is now considered to be part of the Yakama Reservation.

An email has been sent out to those who have hunted it in recent seasons, Bergh tells me, and the nut of it states, “As with all landownerships and jurisdictions, hunting is a privilege and we remind you to please be respectful of landowners’ posted access requirements. While there are no changes to the 2022-23 state hunting regulations within Tract D, please be extra cognizant that Tract D is within the Yakama Nation reservation. We are committed to working with Yakama Nation on long-term management of wildlife within the Tract D area and other geographic areas where we cooperatively manage wildlife with Yakama Nation.”

Bergh’s district prospects can be found here.

Now, about Secretarial Order 3362. It’s the same program as up in Chelan County and in 2020 DOI provided $300,000 to capture and collar 100 Klickitat mule deer does to better map their migration routes “prior to any future events that may adversely affect habitat quality or connectivity.”

Bergh says work began in January 2021 and a quick glance at initial data suggests there may not be as distinct corridors as Emily Jeffries in Wenatchee is seeing, or as extensive as those mapped in the Methow (see above), but it’s information to keep an eye out for down the road if you hunt in Buzz Ramsey’s greater backyard.

COWLITZ BASIN

Deer populations west of the Cascades are far more stable than those to the east (with one big exception that I’ll get to in a bit) and in Southwest Washington, District 10 is a pretty steady producer of 2,000 bucks a fall for riflemen, and about 500 more for other user general season hunters.

“I’ll take the safe bet and predict that harvest will be very similar to years past,” biologist Eric Holman tells me. “This means that we’ll harvest about 2,500 blacktails again in 2022. The only real noticeable exception to this was the 2017 harvest, which dipped below the historic average following the very severe winter of 2016.”

One thing I really like about his hunting prospects is that he breaks down harvest by square mile, giving a density measure for the landscape’s deer productivity. Over the past five years, both the Winston and Coweeman Units have yielded better than a buck a section (1.01 and 1.15, respectively), with Lincoln not far behind (.91). The first two are, of course, mostly dominated by Weyerhaeuser’s fee-access forests, but the third is home to three good-sized jags of state timberland.

And if you’re looking for something a bit bigger than a spike or forked horn, Holman’s data shows that 50 percent of the blacktails taken in Stormking north of Randle are three point or better.

“For experienced hunters I’d suggest that they hunt areas that they are already familiar with,” he tips. “For those new to blacktails I’ll suggest checking out the Hunting Prospects (wdfw.wa.gov/hunting/locations/prospects), choosing an area and then spending time there, possibly grouse hunting before the deer season to help learn the area.”

“For both groups I suggest persistence,” Holman tells me. “Blacktails are tough to hunt because of the secretive nature of the deer and the heavy cover that they inhabit, but there are deer there, so keep trying and give yourself plenty of chances for an opportunity to present itself.”

One other District 10 deer note: This summer, WDFW proposed downlisting Columbian whitetails from endangered to threatened. It won’t translate to hunting opportunity anytime soon, but Holman was pretty stoked by the recovery they’ve made, fueled largely by translocations from Lower Columbia islands to Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge that have doubled a population that once roamed as far north as the glacial outwash plains by Yelm.

“I’ve worked on them on some level since 1995 and it’s exciting to see them making some progress,” Holman tells me, speculating, “Maybe one day a special permit Columbian whitetail deer tag could be a reality in Washington.”

It’s not so far fetched, given that the population in Oregon around Roseburg was federally delisted in 2003 and has supported a limited hunt since 2005 (93 permits were issued this year).

SOUTH COAST

The game units of Grays Harbor and Pacific Counties were among the few last year that, er, bucked the statewide trend, with harvest actually increasing a few ticks. Records going back to at least 2008 suggest that that should continue this season, but June 2021’s extreme heat has biologist Anthony Novack a little bit concerned for this fall’s hunt.

“One big question mark is whether the heat dome that sat over Washington state last summer will have a carryover effect on the blacktail deer population into this year, and subsequent years,” he tells me. “We had 100-degree temperatures occurring right when all of those newly birthed fawns were on the ground. I see the possibility for that hot-weather event to have reduced the survival probabilities of the fawns born last year. Those male fawns born during the heat dome would be our newest cohort of spike deer this season. If the heat dome had an effect on fawn survival, then we might see a drop in total harvest due to fewer available spikes. Spike deer seem to make up 25 to 40 percent of the total harvest in many coastal units.”

With substantial numbers like those, the proof – or lack of it – will show up in how many tags are notched this fall.

“Overall harvest has been pretty stable the last few years and general habitat conditions are good, since a large proportion of the district is managed for commercial timber,” Novack adds. “Anywhere the timber has been harvested within the past 10 years is usually producing a fair amount of forage for our local blacktail.”

His hunting prospects can be found here.

It will come as no surprise, but Capitol Peak – with its high percentage of state land, plentiful clearcuts and lots of hunters – yielded this district’s best harvest density last year, just under a buck per square mile for riflemen and 1.4 bucks a section for all weapons types.

REST OF THE WESTSIDE

Circling back to where all this began, like much of far Eastern Washington, last year saw a pretty bad hemorrhagic disease outbreak among deer in the San Juan Islands and nearby Whidbey Island, this one AHD. Spread by deer-to-deer contact, it delivered a slobberknocker to 2021’s harvest – on Orcas, it shrank from 147 deer in 2020 to 11 last year; on San Juan, 138 down to 22; and on Lopez, 116 to 50.

To be clear, the islands are not exactly deer destinations like Twisp or Colville, and from a biological perspective the dieoff may have helped realign the population with the landscape’s carrying capacity. But in the short term expect far fewer deer here.

Now back to the good news. Since 2001, blacktail harvest has generally increased in the Olympic and Coyle Units on the northeast and east sides of the Olympic Peninsula and last fall saw a sharp spike in the former to 413 deer, a high mark this millennium. The latter unit requires modern firearms hunters to use shotguns. On the other side of Hood Canal, the Kitsap and Mason Units show a similar slow but steady increase in harvest. Bryan Murphie’s district prospects can be found here.

And finally, the mix of national, state and private timberlands to the west and northwest of Mt. Rainier was another part of Washington that saw more deer taken last season, with riflemen accounting for the bulk of that. Given past harvest levels, there could be room for continued growth in the kill. Michelle Tirhi’s district prospects can be found here.

Good luck wherever you hunt!

Top 20 2021 General Rifle Buck Units

Huckleberry, GMU 121: 943

Mount Spokane, GMU 124: 799 (+60 antlerless)

49 Degrees North, GMU 117: 513

Coweeman, GMU 550: 454

Sherman, GMU 101: 443

Skookumchuck, GMU 667: 407

Prescott, GMU 149: 397 (+13 antlerless)

Okanogan East, GMU 204: 387

Winston, GMU 520: 342

Olympic, GMU 621: 331

Washougal, GMU 568: 305

Ryderwood, GMU 530: 291

Battle Ground, GMU 564: 285 (+60 antlerless)

Mason, GMU 633: 280

Beezley, GMU 272: 267

East Klickitat, GMU 382, 267

Satsop, GMU 651: 255

Alladin, GMU 111: 250

Douglas, GMU 108: 245

Ritzville, GMU 284: 243