Skokomish River Border Dispute Rises Again

Leaders of the Skokomish Tribe are directing tribal officials not to agree to next year’s collective salmon seasons with WDFW, an eye-popping development in an ongoing reservation boundary dispute with the state agency, which sees the two issues as separate matters.

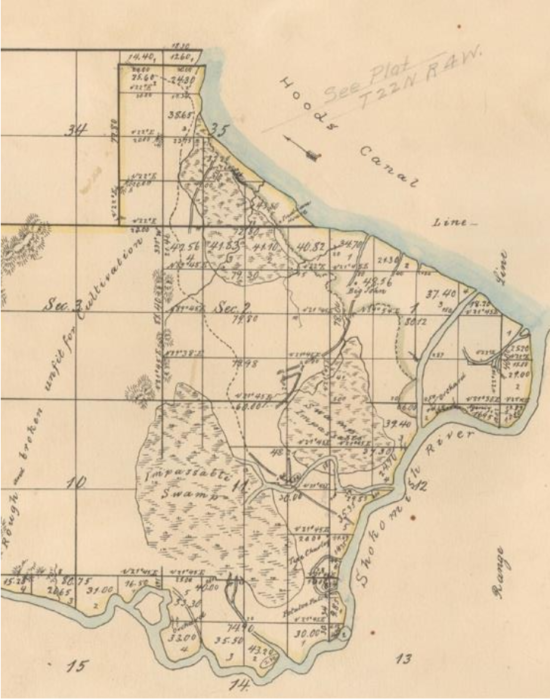

At issue is tribal and state jurisdiction in the 3 1/2 miles of the Skokomish River immediately above Hood Canal.

The tribe contends that their reservation extends across the river to the south bank, based on a 2016 federal opinion from the Department of the Interior’s Solicitor General.

WDFW Director Kelly Susewind rebutted that last year in a letter to Secretary of the Interior David Bernhardt, calling it “an erroneous conclusion” that was “factually and legally deficient,” and now by a 4-0 vote at its late October meeting, the Skokomish Tribal Council passed a resolution terming that response “an affront to our ancestors and … tantamount to an invasion of our territory.”

It also declares that the Skokomish Indian Tribe will “oppose the submission of a joint Tribal-State List of Agreed Fisheries until such time as the State of Washington withdraws its false claims of ownership.”

And for added emphasis, the resolution refers to the stream flowing off the southeast side of the Olympic Mountains as “Skokomish’s River.”

Asked today for comment, WDFW spokeswoman Eryn Couch said the agency is waiting on DOI to complete its review of the matter and that both Director Susewind and Fish and Wildlife Commission Vice Chair Barbara Baker have met with the Skokomish Tribe, which is chaired by Charles “Guy” Miller.

“WDFW will continue to work with the Skokomish Tribe and the federal government to discuss concerns around the North of Falcon process to set salmon seasons, something we see as separate from this issue and therefore should be able to move forward if the situation remains undecided,” Couch said.

How did we get here?

In that 2016 DOI opinion, author Hillary C. Tompkins reaffirmed a regional federal solicitor’s 1971 memorandum that determined the full width of the Skokomish River was part of the reservation.

Tompkins argued that tribal fishers’ weirs “required use and control of the entire width of rivers and their beds,” so an 1855 treaty and an executive order from President Grant reserved it for the Skokomish Tribe.

That has essentially kept WDFW from opening a salmon fishery on the Skokomish downstream of the state’s George Adams Hatchery for the river’s plentiful returning fin-clipped Chinook and coho for each of the past five seasons, frustrating the river’s bank-bound anglers.

They protested in July 2016 and after state negotiations with the tribe stalled in the following years, WDFW appealed in October 2019 to DOI, saying that the state hadn’t had a chance to argue its case to Tompkins but that “our subsequent analysis shows [the opinion] is factually and legally deficient.”

That was based on multiple documents, maps and statements from the late 1800s and early 1900s reviewed by historians Dr. Gail Thompson of Gail Thompson Research of Seattle and Dr. Douglas Littlefield of Littlefield Historical Research in California. Their services were procured by the state Attorney General’s Office.

WDFW wrote that “perhaps the most significant piece of evidence” backing up state ownership comes from an 1874 letter from a federal agent that was discovered in the National Archives.

In it, Edwin Eells states, “The present reservation lies on the North side of the river extending from the mouth about 3 1/2 miles up the river.”

The letter to Eells’ boss in Washington DC was “apparently never discovered or considered” by Tompkins, WDFW argued.

The agency asked DOI to reverse or withdraw Tompkins’ opinion ahead of 2020’s North of Falcon salmon season negotiations.

Those talks occurred months ago without action from the feds and now the 2021 edition of NOF looms this coming winter and early spring.

NOF produces the annual List of Agreed Fisheries that the Skokomish Tribal Council’s resolution refers to. The LOAF between WDFW and the two dozen Western Washington Treaty Tribes spells out the whos, hows and wheres that the harvestable surplus of Chinook, coho and other stocks returning to the region’s rivers will be fished for.

Reaching a deal has become more and more contentious in recent years. What happens when one isn’t signed?

In 2016 the parties couldn’t agree to a package, requiring an extra six weeks of talks, which led to state fishing openers being further delayed into June while federal overseers reviewed the LOAF for compliance with the Endangered Species Act.

The situation with the Skokomish Reservation border is just one of several state-tribal fisheries pots now beginning to boil.

In early October, a North Sound sportfishing organization called Fish Northwest filed a lawsuit in federal court. They don’t believe WDFW is representing their interests adequately at NOF and are asking to be allowed to intervene in the Boldt Decision to gain standing in the case and “enforce” its salmon-sharing provisions.

They’re reacting to WDFW accepting sharp cuts to winter Chinook seasons in the San Juans and nearby waters as part of this year’s LOAF, and forecasted 62-38 tribal-state splits of Chinook this season. As a result of NOF’s structure, they say WDFW “capitulates to whatever harvest allocation the treaty tribes will approve.”

WDFW, tribal and federal attorneys all filed motions to deny Fish Northwest’s lawsuit, but ultimately it is up to U.S. District Court Judge Ricardo S. Martinez in Seattle to rule on the matter.

Also in Puget Sound, after being processed for seven years it appears that the Army Corps of Engineers is finally about to make a decision on permitting WDFW’s new single-lane boat launch at Point No Point, which the Suquamish Tribe has opposed on the grounds it would infringe on treaty fishing rights.

A Corps’ spokesman said they have “an eye on completing the process by the end of January 2021.”

But it’s not all loggerheads between the state and tribes if collaboration on recovering North Nooksack River spring Chinook, expanding Columbia sea lion removals and Puget Sound harbor seal surveys are an indication.