On Weird Wolf Diets, And Washington Deer And Elk Trends

No, they didn’t turn to little kids at bus stops, but when wolves chewed up most all the deer in one area, they did in fact have to look around for a new food source.

They found it in a pretty unlikely species too – a fellow apex predator.

Sea otters.

You might think a headline beginning “Wolves eliminate deer on Alaskan Island …” would have come out of some online wolf-hating fever swamp, but in fact it tops a press release from staid Oregon State University about a new paper OSU and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game collaborated on and that fleshes out the unusual foraging pattern researchers stumbled onto on Pleasant Island and nearby mainland areas around Gustavus, in the upper Panhandle by Glacier Bay.

Wolves colonized the 23,000-acre/36-square-mile uninhabited and undeveloped wilderness island in 2013 and according to researchers’ diet studies, deer made up 75 percent of their meals in 2015, sea otters 25 percent.

However, by 2017 those percentages had shifted markedly, with deer comprising just 7 percent of wolves’ sustenance but sea otters making up 57 percent of their menu.

It’s kind of a mind-bender, researchers acknowledged.

“Sea otters are this famous predator in the near-shore ecosystem and wolves are one of the most famous apex predators in terrestrial systems,” said Taal Levi, an OSU associate professor, in a press release. “So, it’s pretty surprising that sea otters have become the most important resource feeding wolves. You have top predators feeding on a top predator.”

The findings are based on wolf scat samples and the use of “molecular tools” at OSU that helped identify specific wolves and what their diets were comprised of.

Wolves from the Pleasant Island pack were also collared with GPS devices, and those helped determine that the wild canids “are killing sea otters when they are in shallow water or are resting on rocks near shore exposed at low tide,” rather than gnawing on ones that had died in the Inside Passage and washed ashore.

Investigating at least 28 kill sites told ADFG researcher Gretchen Roffler that the sea otter prey selection was widespread and learned quickly.

“So, they aren’t just scavenging sea otters that are dead or dying, they are stalking them and hunting them and killing them and dragging them up onto the land above the high tide line to consume them,” Roffler said in the press release.

The results are counterintuitive.

OSU’s Taal figured that once the wolves ate down the deer on the low, topographically undistinctive island that is partially treed around its perimeter and more open in its boggy uplands, they would depart for greener pastures or die off.

“Instead, the wolves remained and the pack grew to a density not previously seen with wolf populations,” university press release writer Sean Nealon paraphrased Levi as saying.

It’s probably because of how many sea otters there are now.

After being wiped out by the fur trade in the 1700s and 1800s, sea otters were reintroduced to Southeast Alaska in the 1960s and are said to number around 25,000 in the Panhandle today. The marine mammals are protected and can only be taken by Alaska Natives for “subsistence or for traditional handicrafts – fur clothing,” reports National Geographic in its February 2023 issue.

A two-page photo in next month’s magazine shows a Tlingit fur artisan named Christy Ruby boating across a bay with three sea otters she harvested draped over the gunwales. The image illustrates the surprising size northern sea otters can grow to. Males can reach 5 feet long and weigh up to 100 pounds. Some of that weight will be their incredibly dense fur, but below it is a lot of muscle tissue though little fat.

OSU and ADFG’s findings build on previous work that posited “the ongoing expansion of sea otter populations postreintroduction restores an important food source for” wolves. Past research has also found that on islands with or in times of low deer populations, Southeast Alaska wolves rely more on salmon.

The Nat Geo article also takes note of sea otters’ utterly ravenous appetite for shellfish; they consume as much as 25 percent of their body weight a day, which brings them into conflict with crabbers and others. There’s a rising call to again try to reintroduce sea otters to the Oregon Coast, last attempted some 50 years ago in the Cape Arago area. Doing so could help control sea urchins chewing through kelp forests, important to all kinds of fish stocks.

I report this unusual situation with wolves, deer and sea otters against a backdrop of a Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission “blue sheet” on predators and prey. Fed up with the “steady drumbeat” from concerned residents that wolves, cougars and bears have eaten no small amount of game in the northeast and southeast corners of the state, Commissioner John Lehmkuhl of Wenatchee requested WDFW ungulate managers gather statuses, trends and limiting factors affecting the Evergreen State’s deer and elk so, essentially, he could counter locals’ arguments.

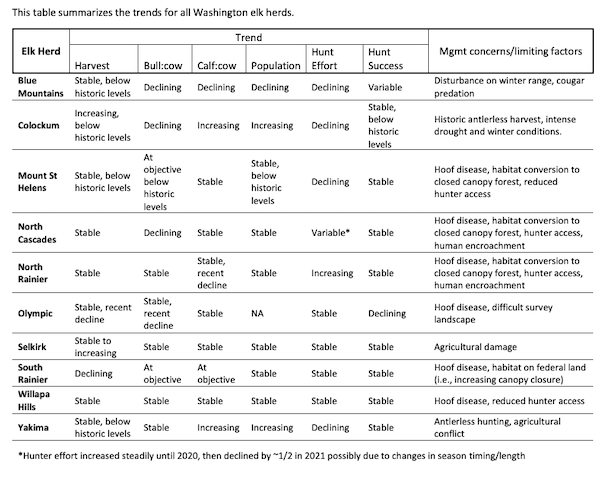

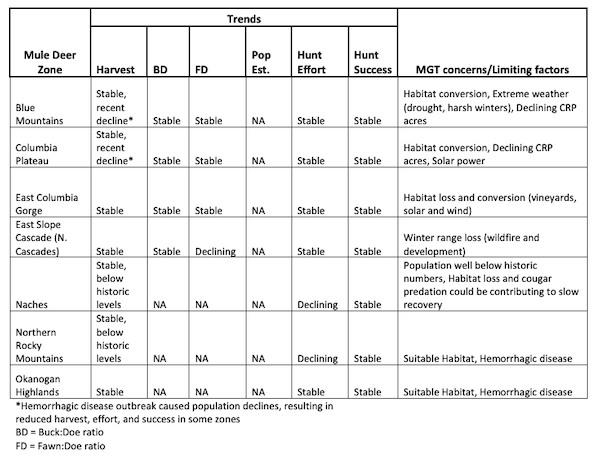

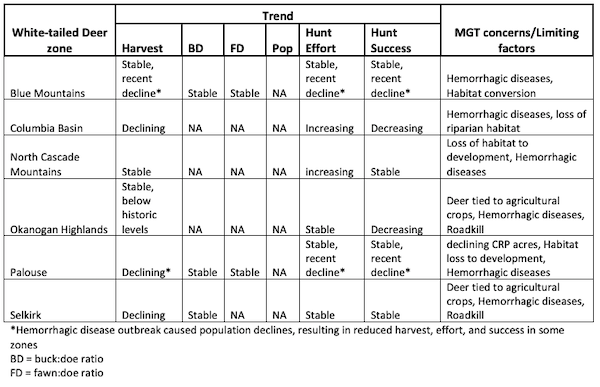

The results will be presented to the commission this Saturday morning, per the meeting agenda, but they’re available now online and make for interesting perusing.

As you’d expect there’s no clear through line for the state’s various elk and deer herds. Some are declining, most are stable, a few are increasing. Hunter harvest, effort and success is generally stable or stable but below historical levels, with notable recent declines and one interesting increase.

Management concerns/limiting factors that WDFW honchoes identified center primarily around habitat issues – forest canopies growing in; conversion of aglands; winter range loss or disturbance; drought – but cougar predation is in fact worrying them in the case of Southeast Washington elk, while recent (Northeast Washington) and long-term disease issues are affecting deer and wapiti numbers and harvests, as is loss of access to former hunting grounds as land is developed and private tree farms charge for access to once-open ground.

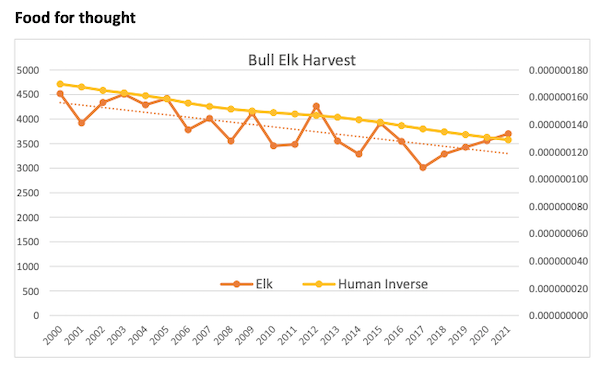

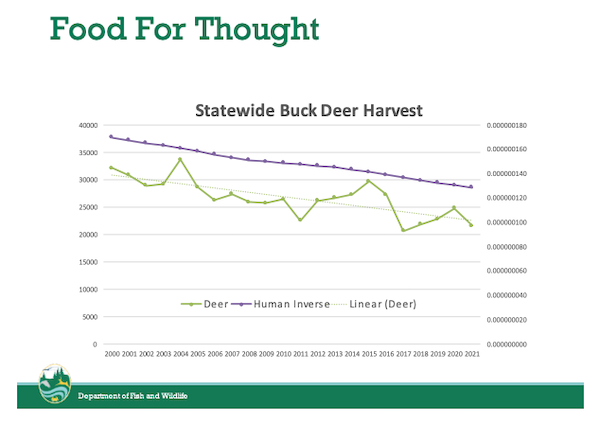

If there is a through line, it is in two “food for thought” graphs that track statewide bull elk and buck deer harvest declines since the year 2000. Their trend lines are paralleled by a line showing an inverted human population trend for Washington – basically, while the real population is of course increasing, if you divide that number by 1 you can show it as a decrease. Washington is the smallest Western state and has the second highest human population and density, as WDFW often notes.

Correlation is not causation – well, Pleasant Island, Alaska, deer might beg to differ – but the agency staffer who came up with the clever graphs explains:

“This helps demonstrate how statewide Bull elk harvest has a similar downward trend to the inverse of population growth.”

And:

“This helps demonstrate how statewide all buck deer harvest for all species has a similar downward trend to the inverse of population growth.”

It will be interesting to watch WDFW’s in-person status and trend presentations and any commission discussion afterwards on Saturday morning. There’s no one single cause for the ills of big game, but in a few cases there can be.