NWIFC Chair Again Weighs In On WDFW Commission Draft Conservation Policy

The head of a powerful Western Washington tribal organization is taking another shot at the state Fish and Wildlife Commission’s draft Conservation Policy, saying that if it’s meant to offer guidance without regulatory muscle, it should be “adopted as a vision statement” instead.

Ed Johnstone, chair of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission, also contrasts it with the WDFW oversight panel’s recently adopted Comanager Hatchery Policy, terming it “two steps backward” to the fish production accord’s “step in the right direction,” and says the commission needs to engage with the tribes “instead of trying to redefine conservation unilaterally.”

“With vague language and no measurable outcomes, the draft conservation policy has too many problems for us to offer valuable input. We don’t disagree that ‘humankind is in the midst of a biodiversity extinction crisis and must act now,’ as the draft states. However, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife does not have the authority or resources to reverse the causes of declining biodiversity,” Johnstone writes in his monthly Being Frank column for November.

“The hard work of protecting habitat will require more than a policy statement. To reverse the trend of habitat loss that stands in the way of salmon recovery, other state agencies need to step up as well, with new authorities, regulations, and a lot more political will to prevent ongoing degradation caused by development and climate change,” he adds.

The commission’s draft Conservation Policy was first made public in September 2021 and immediately drew fire. It has resurfaced from time to time since, with Johnstone also commenting on it as NWIFC chair this past June.

Most recently, it was a topic at the state Fish and Wildlife Commission’s late October meetings, when two members demanded that the policy be voted on by the end of 2023. A high-ranking WDFW honcho’s timeline that suggested it couldn’t come up for a vote before mid-June 2024 to be able to present it to tribes around the state and possibly hold government-to-government meetings was called “absolutely absurd.”

What might also be absurd is the all-consuming need to pass the policy as soon as possible even though in one of its defenders’ words it “doesn’t even suggest we’re going to do anything different than we’re doing right now.” The dichotomy creates a lack of trust.

According to Fish and Wildlife Commission Chair Barbara Baker, the policy is meant to “serve as overarching guidance to inform a variety of Department decisions relative to budget development, setting priorities, and the management of fish and wildlife.” Baker has also said that part of the goal is to define the word conservation, used nearly four dozen times in WDFW’s 25-year strategic plan but which is silent on its meaning.

Responding in his monthly column, Johnstone states, “If the goal is to provide guidance and not regulatory authority, it should be adopted as a vision statement. We’ve been assured that the policy is not meant to interfere with tribes’ treaty-protected rights, but WDFW does have a regulatory role in permitting some of our restoration projects, land use and enforcement interactions. Regardless of the intent behind this conservation policy, its ambiguous wording could stand in the way of tribes’ work to recover salmon if misinterpreted by anyone trying to implement it.”

“And if our co-manager wants to put conservation first, it needs to take responsibility for human impacts to the ecosystem by accurately accounting for under-regulated, under-monitored and under-enforced recreational uses of the state’s lands and waters. This can be done without trying to redefine conservation,” he adds.

Referencing the Boldt Decision, which turns a half century this coming February, Johnstone adds that the Fish and Wildlife Commission needs to honor the comanager “relationship by engaging with tribes first instead of trying to redefine conservation unilaterally.”

(A subtext to his column is that Johnstone’s tribe, the Quinault Indian Nation, engaged in a recent PR battle with WDFW over Grays Harbor coho fishing. QIN suspended its commercial fishery over its stated concern that the return was weak and then attempted to use the court of public opinion to get WDFW to close its seasons, but the state agency held firm based on its own run indicators.)

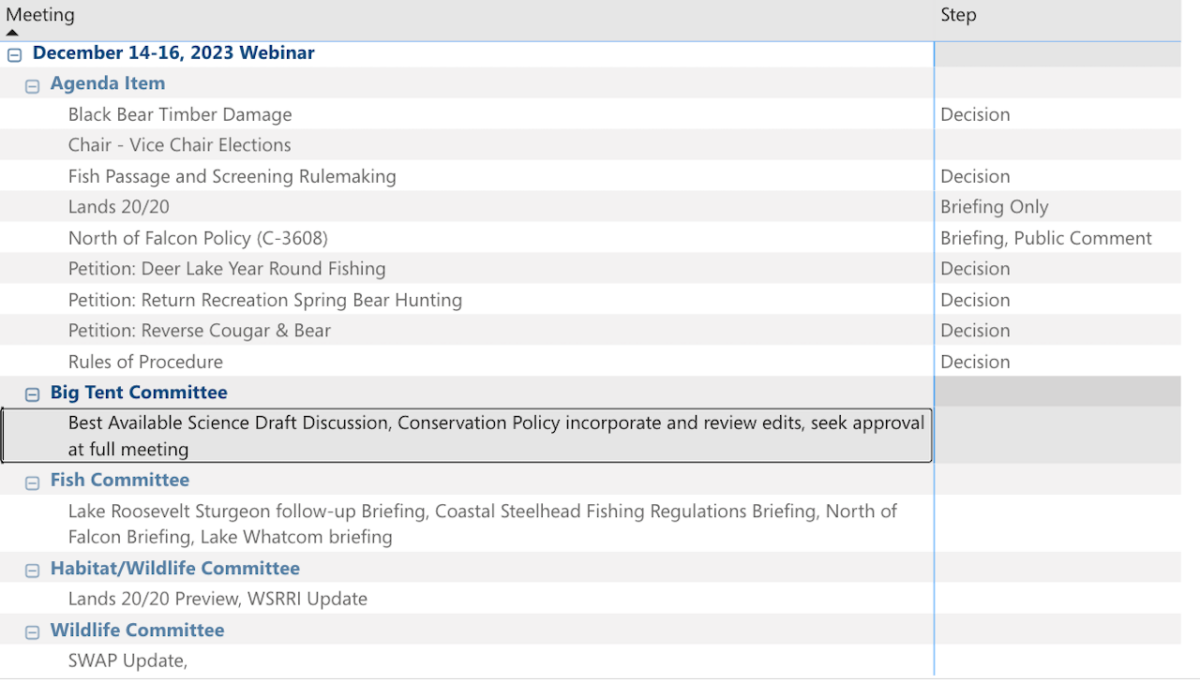

As it stands, a rough draft of the commission’s December 14-16 meeting agenda lists “Conservation Policy incorporate and review edits, seek approval at full meeting” under Chair Baker’s Big Tent Committee.