Northwest Salmon Season-setting Process Kicks Off With Oregon Coast Forecasting

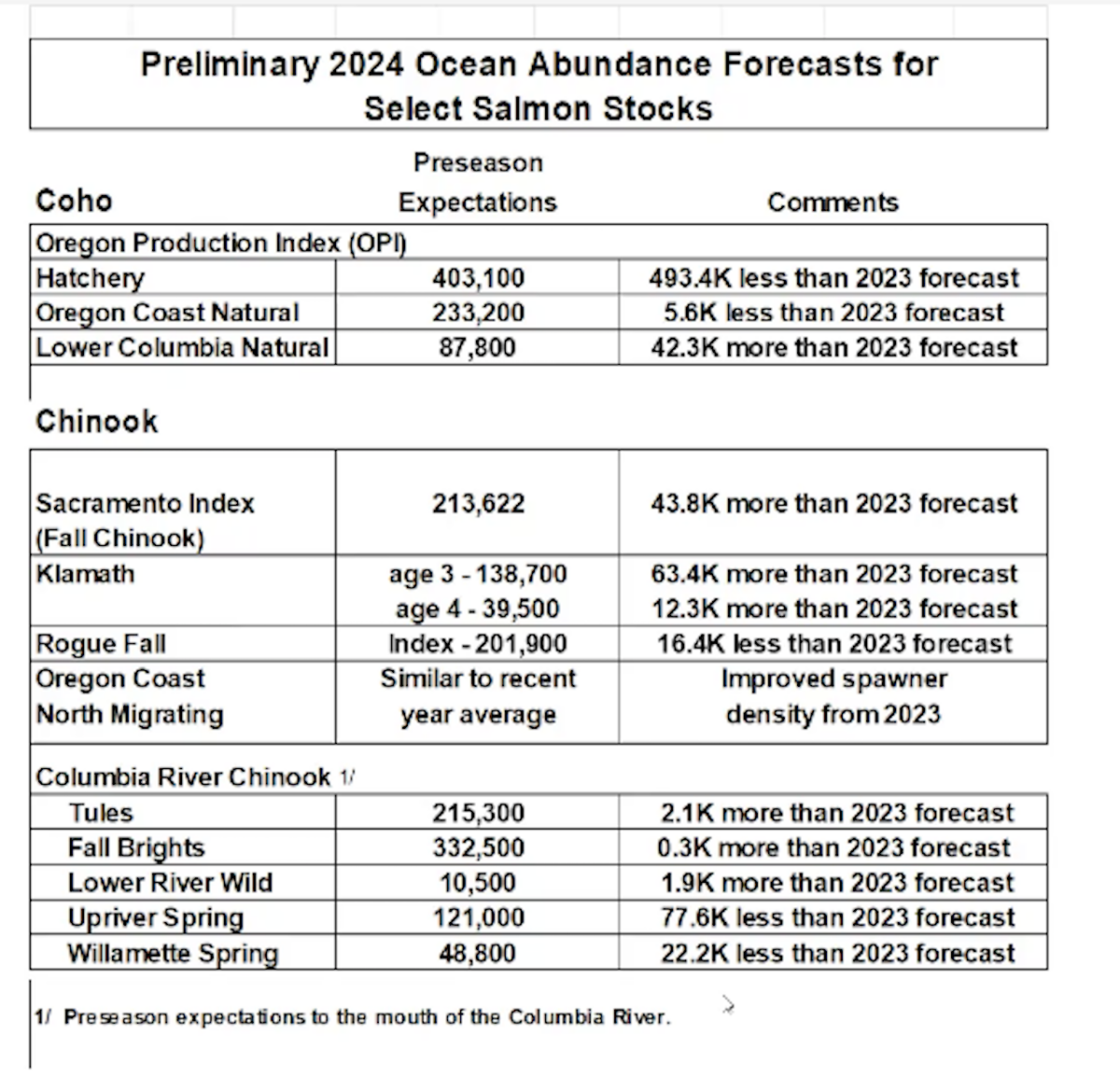

A new Columbia River hatchery coho forecasting model, new tule Chinook harvest matrix and more 2024 West Coast salmon predictions are being rolled out this week for public perusal.

In the first of three successive meetings on all things Northwest Oncorhynchus, ODFW today also briefed Oregon Coast fishermen about last year’s harvests and escapements, this year’s king and silver ocean abundances, and the limiting factors and constraints they and other state, federal and tribal managers will be coping with over the next month and a half as they attempt to shape this summer and fall’s seasons with the angling public and others.

Yes, sir and ma’am, North of Falcon, South of Falcon and All Points In Between Falcon has officially begun, with a meeting tonight on Washington’s Grays Harbor and Willapa Bay forecasts, and WDFW’s big coastal and Puget Sound unveil on Friday.

So far, there haven’t been any eye-popping 2024 predictions (save one; see below) or season-shattering pronouncements like last year, but there is a new bubble-tempering model to estimate how many Columbia River hatchery coho are swimming out there in the briny blue.

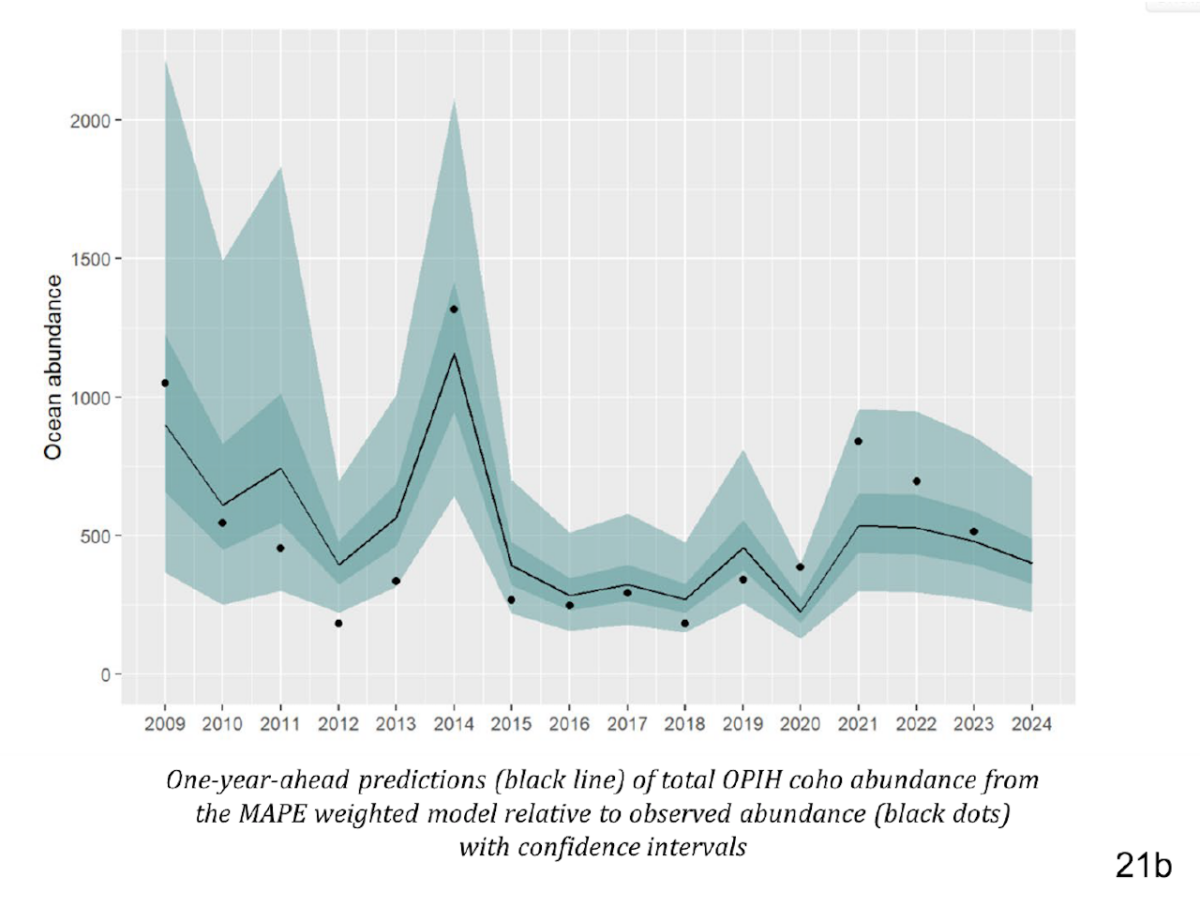

The old model was based on one season’s jack returns and that same year-class’s smolt outmigration from the big river, but it has been “overforecasting in many recent years, often by quite a bit,” Cassie Leeman, a member of ODFW’s Salmon Technical Team, said during today’s meeting in Newport and carried online via Teams.

Where the prediction tool is said to have “performed well” from the early 1980s into the early 2010s, from 2015 on it has “performed poorly” in most years.

For instance, last year’s forecast called for just under 900,000 Columbia marked coho in the Pacific, but postseason run reconstruction showed only 514,000 actually were. That and strong Oregon Coast natural coho production likely led to way overforecasted mark rates in summer selective fisheries on the ocean.

So a new model has been developed. It still uses those jack and smolt figures, but also nine marine environmental indicators known to influence salmon survival such as sea surface temperatures and ocean upwelling, according to Leeman.

All of those factors were then used to come up with some 1,500 different model combinations. Then after hindcasting with each to see how they fared against actual abundances seen over the last 15 years, the top 10 models were used to make an ensemble forecast.

Anybody who has been paying attention this winter to meteorologists like Cliff Mass, Michael Snyder, Mark Nelsen, etc., etc., etc., knows about the power of ensemble forecasting versus using a single model to predict the weather.

Leeman says that the new hatchery coho model is “much better than what we’ve been using.”

It was 40 percent better at predicting actual ocean abundance than the old tool, and it was only 7 percent off when used to hindcast 2023 – “pretty impressive.”

It spit out a forecast of 403,000 clipped Columbia coho for this year in the ocean, or just under 500,000 fewer than the old model claimed for 2023.

While there is risk in putting all your eggs into one shiny new basket, ODFW’s John North pointed out similar modeling has been used in recent years to forecast Columbia springers and it has helped to reduce the extremes seen in predictions.

It was also signed off on by the Pacific Fisheries Management Council, which requested it to better predict Columbia hatchery coho.

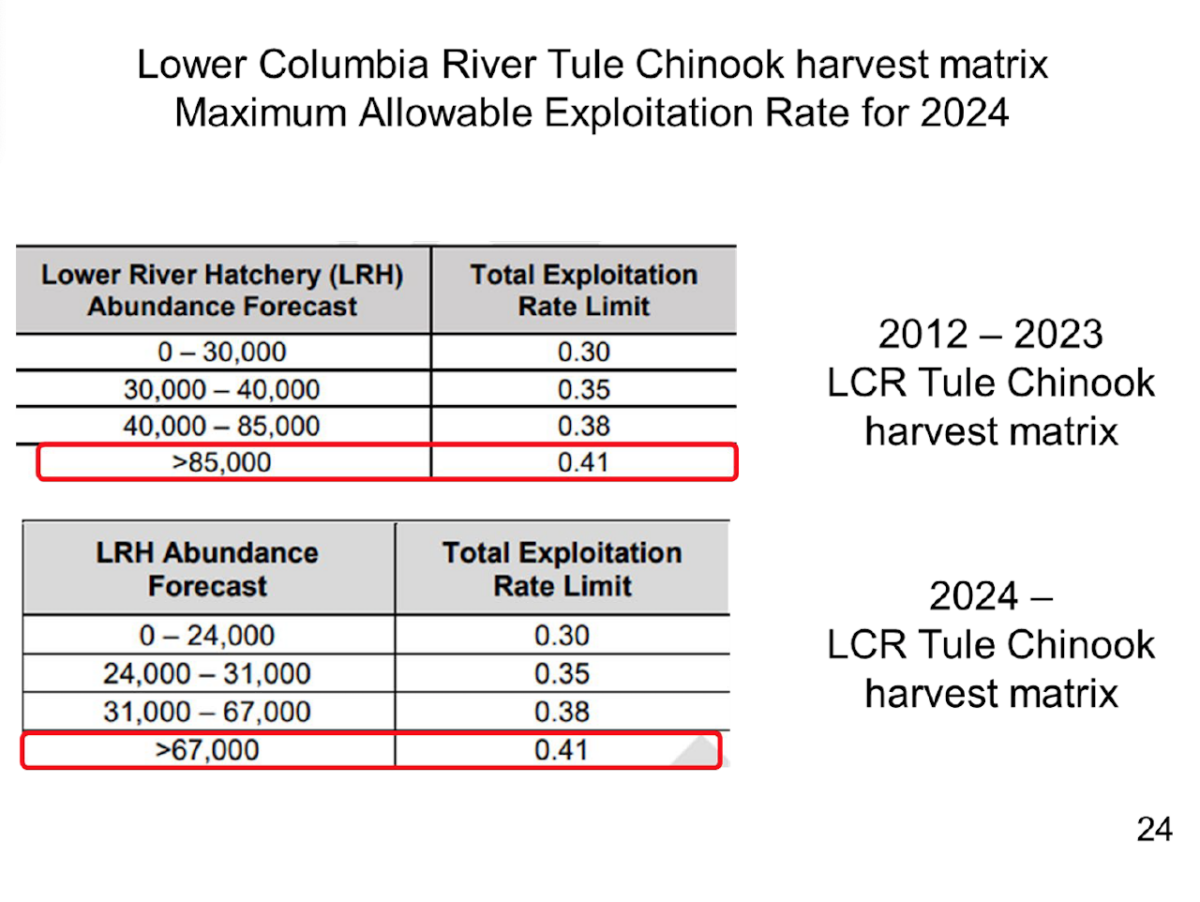

As for that new tule Chinook matrix, it reduces the number of this ESA-listed Lower Columbia largely hatchery stock that is needed to allow for certain exploitation rates, or what percentage of the run can be harvested in the ocean and river, by 21 percent.

For instance, the old matrix required a forecast of 85,000-plus for the maximum ER of 41 percent and 40,000 to 85,000 for an ER of 38 percent, which has been used in recent years, constraining fisheries. Under the new matrix, a forecast of 67,000-plus is all that is required for a 41 percent ER, 31,000 to 67,000 for a 38 percent ER.

The change is related to reduced hatchery production, from 22 million smolts a year to 17 million and managers being able to convince the National Marine Fisheries Service to change the matrix commensurately, an ODFW official explained.

The tule ER is split between Alaska and British Columbia, Washington Coast treaty and nontreaty, South of Falcon, and Columbia fisheries. It can vary by year, but in 2023, it broke out thusly: 28.6 percent for ocean fisheries – 0.4 percent South of Falcon non-treaty; 9.4 percent NOF non-treaty; 2.2 percent NOF treaty; and 16.6 percent northern intercept – and 9.4 percent for in-river fisheries, per the DFWs’ management plan.

While Klamath and Sacramento Chinook forecasts are up over last year – which saw draconian king retention closures on most Oregon offshore waters to protect the two California stocks – given continuing low abundances that are a “far cry” from past decades, as well as uncertainty around the impact of ongoing Klamath dam removal and still-to-be-determined guidance from NMFS for this season, opportunities remain TBD at this point.

“Don’t expect a full Chinook season; that’s not going to happen,” underlined Eric Schindler, ODFW’s ocean sampling project leader.

If anything’s more settled, it might be Oregon Coast wild coho seasons. Thanks to the parents of 2024’s year-class doing pretty good at seeding the streams in 2021 and “medium” marine survival for their progeny the past year or so, a higher impact rate is in play in the Pacific relative to 2023.

Adds ODFW about coastal river fisheries, “Similar wild coho seasons to last year are anticipated.”

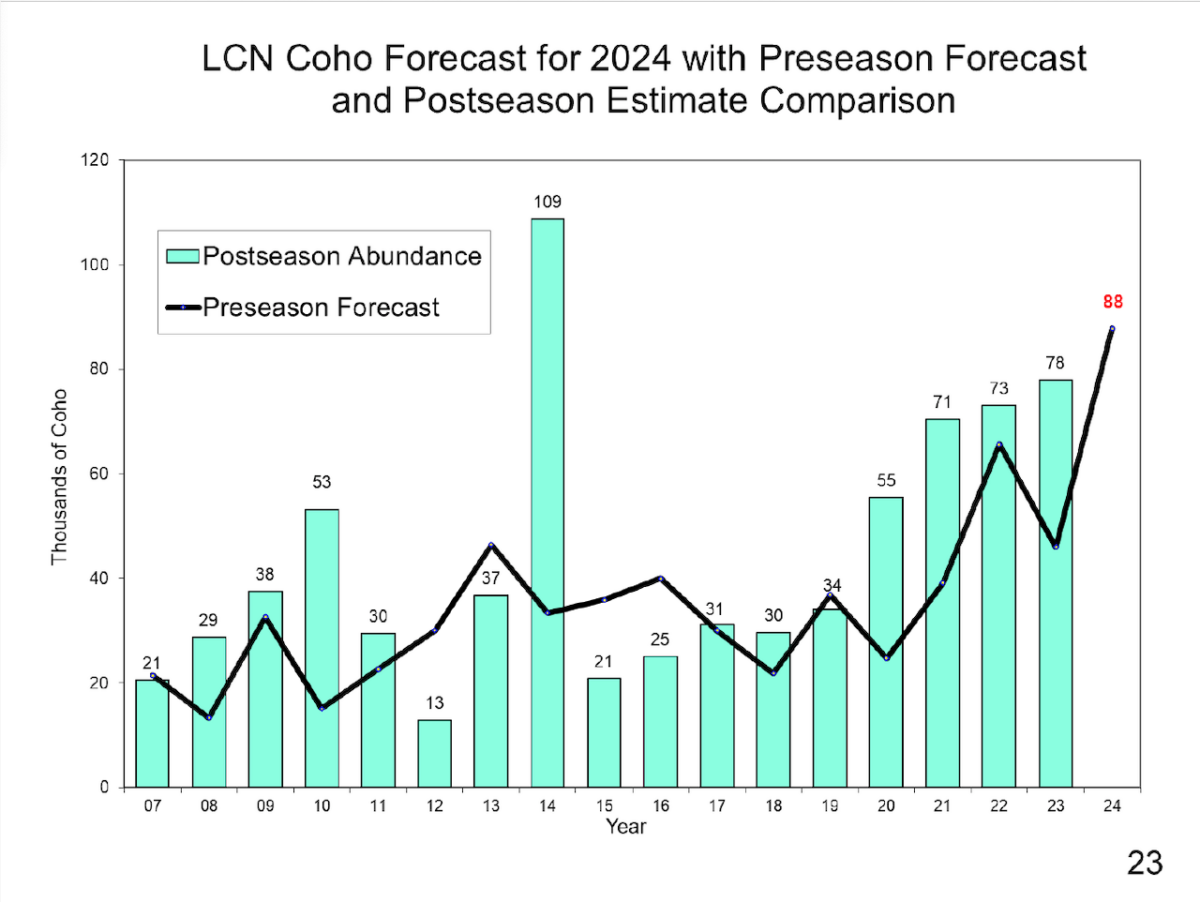

One more positive coho note: The forecast for ESA-listed Lower Columbia naturals, or LCNs, is twice as big as last year’s prediction, 87,800 versus 45,500, and is the “highest we’ve ever seen,” said Leeman.

It continues a trend of increasing abundance for these unclipped salmon returning to streams below the Big White Salmon and Hood Rivers since the early 2000s and the listing. And while this year’s bump is mainly expected on Washington tributaries, the forecast might/may/could/possibly offer some sort of early forsoothery about relative run strength past Willamette Falls, above which adipose-finned coho can be kept because they aren’t listed and last year saw a record.

Or maybe it doesn’t offer any sort of hope.

Either way, 2024 salmon season setting is here on both sides of that Oregon Coast promontory known as Falcon.

Special bonus fun fact: Cape Falcon was named in the late 1700s by Spanish sailor Bruno de Heceta for a 13th century and 14th century Italian boss nun, Clare of Montefalco.