New Study Looks At Northeast Washington Elk, Wolf, Lion, Human Interactions

A new paper on Northeast Washington elk, wolves and cougars will give hunters and local residents – themselves active participants in this dynamic interplay – some things to chew on.

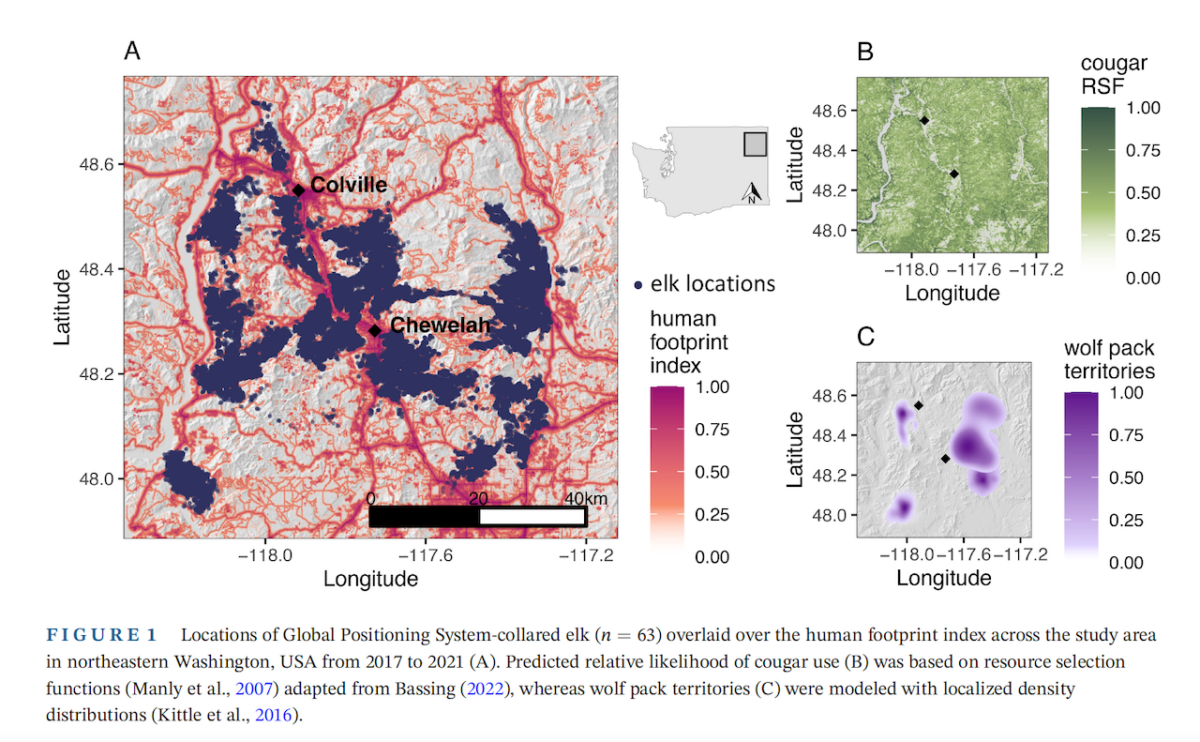

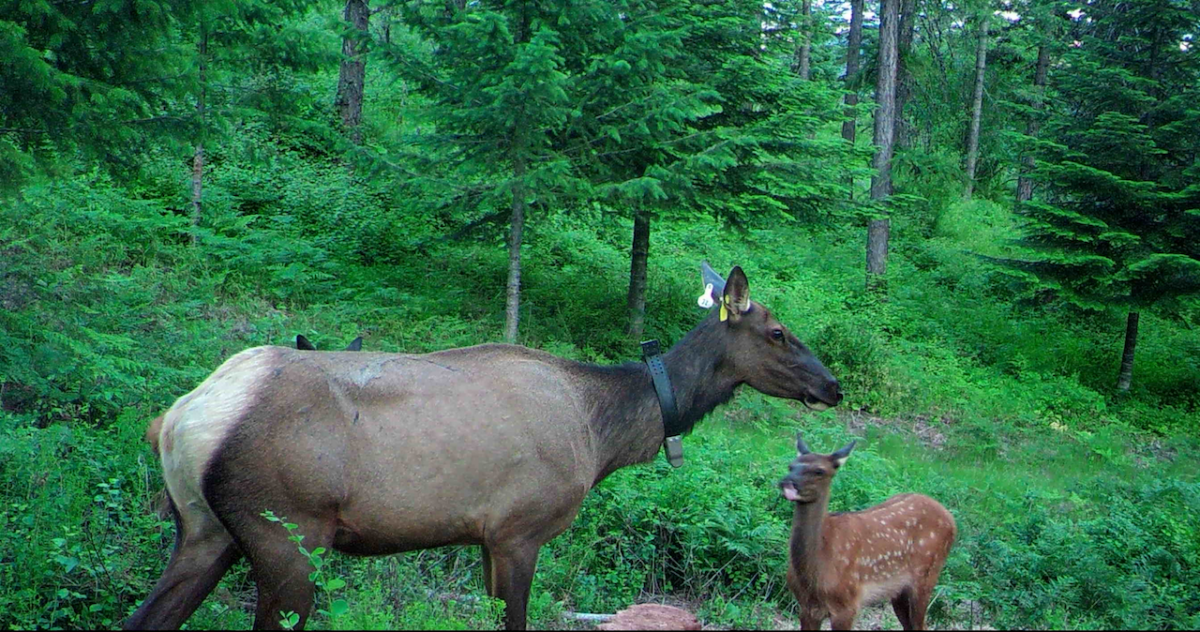

Researchers with the University of Washington, state Department of Fish and Wildlife and a local tribe used four years worth of data from GPS collars placed on 93 wapiti, 42 lions and 16 of the long-legged lopers to figure out where elk chose to hang out on this varied and far-from-pristine landscape in summer and fall.

They found that elk always tried to avoid wolves regardless of time of day or either season, but while the herding animals strongly stayed away from cougar country at night, they were less worried about encountering big cats during daylight.

When it came to humans, however, it was the opposite: Elk tend to avoid us during the day but moved closer to homes and farms at night to apparently use them as something of a shield against wolves.

That surprised the authors and it’s a finding that is helping to better flesh out how a growing herd of ungulates is somehow navigating a growing wolf population in an environment far, far different from Yellowstone National Park, where past wolf work – trophic cascade, beavers, rivers and all that – is also being reconsidered.

“Elk responses to wolves ran counter to our predictions for this coursing predator, potentially owing to the pervasive role of humans in this system. Our study revealed the importance of accounting for (around the clock) variation in animal movement and highlights critical differences in the impacts of cougars, wolves, and humans on their shared ungulate prey,” write UW’s Taylor Ganz, Aaron Wirsing, Sarah Bassing and Laura Prugh, WDFW’s Melia DeVivo and Brian Kertson, and the Spokane Tribe of Indian’s Savanah Walker.

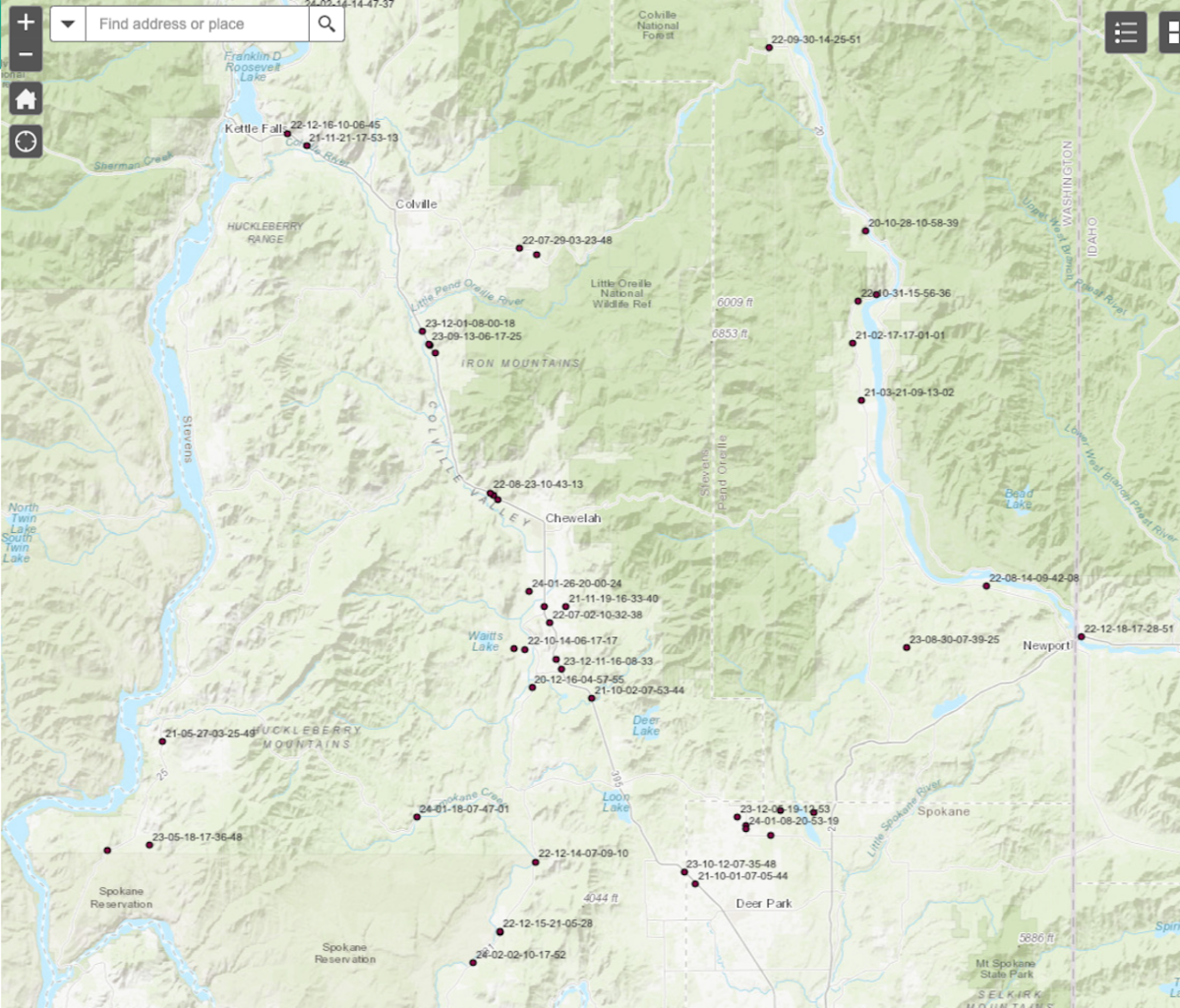

Their paper was just published in the journal Ecology and it represents the latest research from the UW and WDFW‘s very interesting Washington Predator-Prey Project. This particular study stretched roughly from the upper half of Lake Roosevelt on the west to the Pend Oreille River valley on the east, Fort Spokane and Deer Park on the south to Kettle Falls and Ione on the north.

Essentially “leveraging a rare dataset” that uses GPS data to track both the toothsome and the tasty across this region of farm- and small-town-dotted valley floors, forested hillsides and scattered homes, and clearcuts, mines and mountains at higher elevations, the work also provides another glimpse into who is eating who, always interesting information for hunters.

Of 63 cow elk collared between 2017 and 2021, 14 died, including six harvested by hunters, three hit by vehicles and two recorded as hunter wounding loss. Of the three other cow mortalities, two died from an unknown disease while the third succumbed to an unknown cause.

While 15 of 30 collared elk calves (16 girls, 14 boys) lived to see their first birthday, 11 are known to have died; the collars dropped off the other four, so it’s unclear what happened to them. Of the 11 confirmed mortalities, three calves were killed by cougars, two by bears and one after becoming entangled in a fence. Of the remaining five calves, which all officially died of unknown causes, black bears are “suspected” in the deaths of three – spring bruin permit hunting was kiboshed by the Fish and Wildlife Commission – and coyotes might have gotten a fourth.

“There were no confirmed cases of wolves killing collared elk during the study,” the authors wrote.

It’s surprising that that can be possible, given the biological realities for both species – elk tend to prefer more open ground and wolves prefer to test prey over similar landscapes – and conventional wisdom that wolves eat all the elk.

But the study does help shine a light on the wary dance of wildlife across this particular stage.

While the range of these elk overlaps that of wolves, they also avoided core pack areas in summer and in fall reduced their use of wolf territory further.

“These patterns may be explained by wolf biology, human influences, or both. Wolf pups in Washington are typically born in mid to late April, such that a pack is typically anchored to a den site when elk calf parturition begins (about) 1 month later. In the summer, elk may be able to use areas within wolf pack territories with relative safety by avoiding den and rendezvous sites. Conversely, wolves range more widely in the fall, potentially making encounter risk more unpredictable for elk and necessitating broader avoidance of wolf pack territories to reduce risk,” Ganz and her fellow researchers state.

They also found that cow elk with calves avoided wolves “to an especially strong degree” in the high season, and moms and young found themselves more often near areas “with a relatively high human footprint” at night in summer than in fall.

“In many ways, elk responses to wolves in this system differed from what has been observed in protected areas, potentially reflecting habitat structure, predator density and human influences,” the authors write.

They also posit that with cougar numbers far greater than wolves and more evenly distributed across the landscape, lions just might represent a risk that elk can’t mitigate against except to use open areas at night when cougars are most likely to be hunting and take their chances the rest of the day.

Interestingly, Northeast Washington wolves were found to prefer forested areas, “perhaps to avoid humans,” and a diet analysis found that they’re feeding on moose there.

The researchers note that that dietary data has yet to be published, but it does gel with a Predator-Prey Project video from last summer that stated the region’s wolves “rely primarily on moose in summer; whitetailed deer in winter.”

That too will catch the attention of hunters, and last month WDFW announced that it planned to begin capturing cow moose in the same area as this research looked at to assess survival and population trends, data that will also inform the number of special permits available in local game management units.

For elk, moving out of the woods and toward open ground in areas where there are more wolves “may have reduced the risk” of encountering those moose-eating packs, the paper’s authors write.

Wapiti are smart critters and they balance the risks of being eaten by wolves and cougars in unique ways, this research is showing. They cozy up to humans who also hunt them, though only when their risk of being killed is minimized.

But that behavior also comes with a caveat: “Elk leveraging the human shield could increasingly come into conflict with humans,” Ganz et al state.

Think vehicle-elk collisions, crop damage and nuisance animals like Buttons the Elk and Packwood’s Hammock Head.

“Thus, continued research on the effects of humans on predator–prey interactions is vital to sustaining wildlife populations outside of protected areas,” they say.

It all provides a lot to mull about the weird ways of Washington wildlife, and no doubt will elicit challenges from the public at large unlike that past Yellowstone work because of these animals’ close proximity to a wide range of humans and their long-term observations.

Just this week, a pic of a big herd of elk in a pasture in broad daylight between Colville and Chewelah popped up on Facebook. When I cheerfully brought it to Ganz’s attention, she emailed back, “A good reminder that even if the trend is for most of the elk to do something most of the time, that won’t always be the case!”

It was outside the scope of this paper, but I wonder if wolf collar data shows as strong of an avoidance to farms and homes at night when it comes to the region’s cattle operations, or if there’s a human density dependence to that facet. And I wonder how predators are supposed to heal the ecosystem if their prey doesn’t act in orthodox ways?

OK, that last one’s a little snarky, but I’ve fiddle-farted around with this long enough and need to get some Actual Work done today.

Before I go, I want to note that funding for Ganz and crew came from WDFW, UW, the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation and National Science Foundation, they reported in their paper.

And for more on it, see Michael Wright’s article out today in Spokane’s Spokesman-Review.