More Ram Permits For Bighorn Herd After Pneumonia Confirmed In Dead Lamb?

In a very unusual midseason move, Washington wildlife officials may grant additional bighorn ram hunting permits for one herd this fall after a dead lamb tested positive for a lethal bacteria.

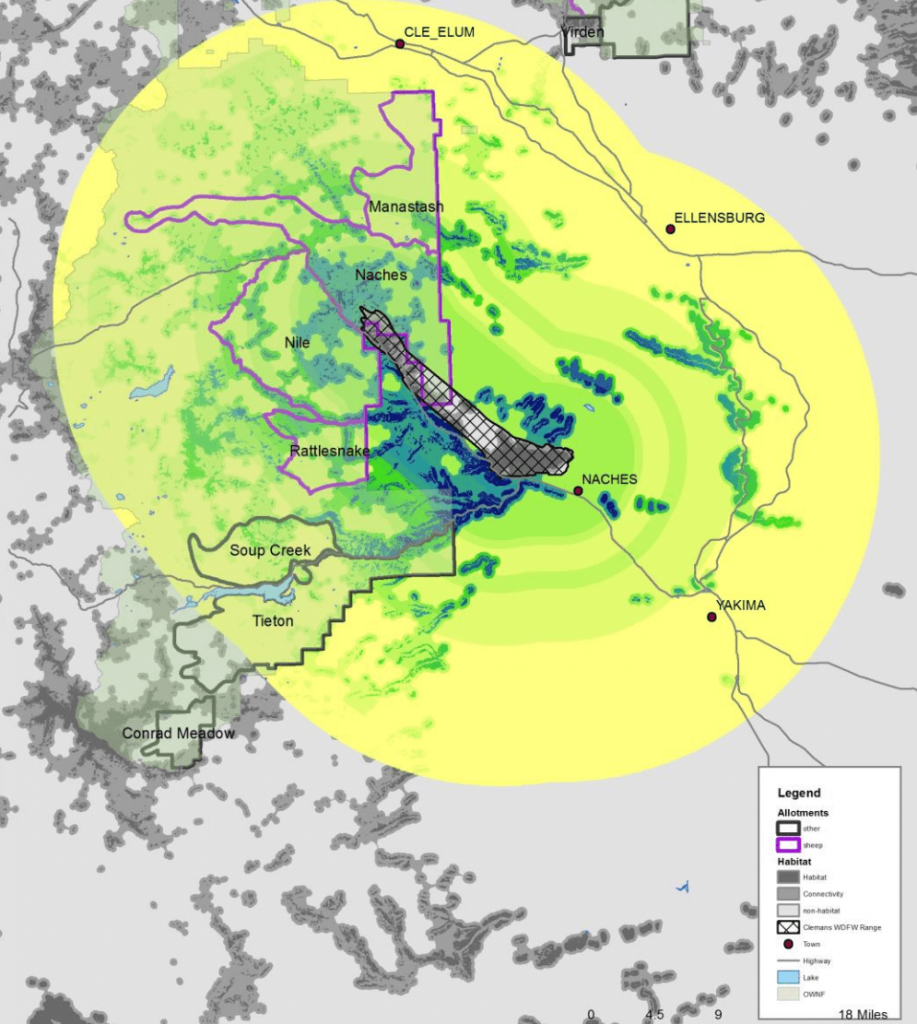

The move could “seize a little opportunity” from a disturbing developing situation with the 250- to 300-strong Cleman Mountain Herd in Yakima County – wild sheep that until now weren’t known to be infected by Movi and which in the past WDFW has gone to extreme lengths to keep free of the disease.

Director Kelly Susewind briefed the Fish and Wildlife Commission about the possibility this morning during his report to the nine-member citizen panel.

“We might want to offer some additional hunts for the next tier down, for folks not drawn” earlier this year during the spring special permit application process, he said.

News about the deceased lamb, as well as several others that were acting lethargic, emerged earlier this week after a ram hunter observed the animals in early October and reported his sighting to WDFW biologists.

They went to the scene and found the dead sheep. Samples that were tested came back positive for Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae. Samples from the hunter’s bighorn tested negative.

Domestic sheep and goats are the most common carriers of the disease. Unlike wild brethren, they’re typically unaffected by it or have only mild issues. However, there’s no treatment or vaccine for bighorns.

Susewind said WDFW is waiting on lab work to determine what strain of Movi the dead lamb fell victim to.

For the moment WDFW is monitoring its herd, which roams the long basalt anticlinal ridge known as Cleman Mountain, north of Highway 410 between Naches and the Nile area.

It’s also asking the public to report any abnormal behavior. Signs of sickness in bighorns include coughing.

And any animals taken by bighorn hunters still trying to fill their permits will be tested to get a sense of how widespread Movi may or may not be in the herd.

Earlier this week WDFW said that largescale removal of animals “was not the best option at this time.”

In 2013, the agency took out the entire nearby Tieton Herd, 57 bighorns, to prevent Movi from infecting the Cleman Mountain Herd.

Dozens upon dozens of bighorns in the Umtanum/Yakima Canyon Herd also had to be destroyed in 2009. Those animals are the closest to the Cleman sheep.

However, taking out animals in a more limited fashion through select sanctioned harvest is now being mulled.

“It’s not a done deal yet because there are a substantial number of details that still need to be worked out,” stated agency ungulate manager Brock Hoenes this morning.

And in a compressed timeline.

“The main hurdles will be getting the hunt in before winter weather pushes the sheep down to the feed sites,” Hoenes said when asked for more details. “From an ethical and fair chase perspective, we simply can’t allow these hunts to occur when the sheep are concentrated in those areas.”

The sites include one along Old Naches Highway near the Highways 12-410 junction. They’re popular with wildlife viewers.

“The second thing will be making sure we can provide hunters with the latitude to decline the opportunity if they so choose,” Hoenes added. “Maybe they don’t have the time to take advantage or might view it as a lesser opportunity because the choicest rams may have already been harvested. Some may not want to use their points on that opportunity.”

Two tribes also hunt Cleman Mountain bighorns, the Muckleshoot Tribe and Yakama Nation.

To Hoenes’ knowledge, there hasn’t been a similar instance of WDFW granting additional permits midway through a hunting season.

The tenth month of 2020 has been a tough one for Washington’s 1,700 or so bighorns.

Early last week a dozen wild sheep in the Quilomene near Vantage had to be killed by state gunners after a loose diseased domestic ewe came in contact with their herd in late September.

Ultimately the 12 tested negative for pneumonia, making it seem to some like the operation wasn’t worthwhile.

“It is difficult to see the lethal removal of bighorns under these circumstances, but it is important to understand that the overall health of the herd trumps the health of individual animals,” Andrew Kelso of the Washington Wild Sheep Foundation told me. “Movi is easily spread amongst bighorn sheep and the timing of this event coincided with the pending rut. While we believe it would have been preferable to live capture and test animals, the amount of time for such an operation to be planned and carried out may have been prohibitive. Acting fast to prevent the spread of disease and gather data was critical to establishing an action plan to protect the entire Quilomene herd.”

As for where that particular domestic ewe came from, that remains unclear. It had been missing since at least Sept. 13.

That’s about the time that livestock start to come off public lands allotments, and the nearest grazing leases are DNR and US Forest Service allotments on either side of Blewett Pass.

The Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest told John Kruse of Northwestern Outdoors Radio that it didn’t come off of one of theirs and that their investigation pointed to a private lands source instead. By chance there was a depredation on a lamb north of Ellensburg on Sept. 8.

The sheep’s origin was danced around during today’s commission meeting. Commissioner Kim Thorburn of Spokane pointed out it was a “long way from anywhere” that it should have been grazing.

“What is our thinking on that?” she asked Director Susewind.

“The ewe was in a place it really shouldn’t have been,” he said.

Without saying where it had come from, Susewind said that WDFW was working with “big and small” producers alike, as well as USFS, to maintain the “greatest distance” possible between domestic and wild herds.

Washington Wild Sheep Foundation along with Conservation Northwest are also working toward that end.

“It is important to remember that the true issue at hand is the need for separation of domestic and wild sheep,” said WAWSF’s Kelso.

The same 2016 Forest Service analysis that predicted that the Quilomene bighorns were one of the least likely herds to encounter domestic sheep from national forest grazing allotments also found that the Cleman Mountain Herd faced one of the highest probabilities, as they overlap at least one federal lease, the Naches.

“The Cleman herd is at high risk of contracting bacteria associated with pneumonia outbreaks due to nearby domestic sheep grazing allotments,” confirms WDFW’s 2019 Game Status and Trend Report, the most recent from the agency. “Concerns have led to frequent testing; the most recent testing was in January 2017. No evidence of pneumonia or associated bacteria was detected.”

Hoenes confirmed today that the herd had been disease-free until the dead lamb tested positive.

Commissioner Thorburn noted that domestic sheep mingling with bighorns and transmitting pneumonia is a problem throughout the West.

The effects last for years and years – a decade so far in the case of one Washington herd.

The 2009 outbreak in the Umtanum/Yakima wild sheep led to “a series of lamb recruitment failures” as the young bighorns continue to fall victim to pneumonia apparently carried by their parents. Their herd is still in decline as a result, per WDFW.

It may seem backwards to some, but to help that herd become disease-free, last year WDFW boosted adult ram permit levels and offered new tags for ewes and young rams in an effort to “reduce the population to a size where spreaders can be found and selectively removed” later by biologists using a “test and cull” approach.

However, hunters mostly shot rams instead of ewes, and several of those rams were considered to be adults – i.e., 4-plus-year-olds – instead of juveniles, according to WDFW.

This new idea would be the opposite.

Stay tuned.