More On CWD Discovery In Western ID Deer, States’ Response

Editor’s note: This story has been updated at 12:10 p.m., 11-18-21, with a new second, 13th and 14th paragraphs on WDFW and ODFW reactions.

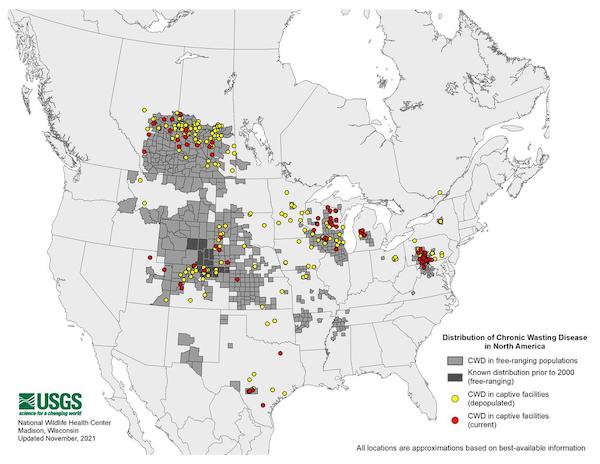

Chronic wasting disease’s leapfrog into westcentral Idaho has left state wildlife officials there “very surprised” that it appeared so far from other sources of the fatal deer family malady, and it also has neighboring CWD-free states reacting as well.

In a late morning update to this story, WDFW says it will ask Washington hunters who harvest deer, elk or moose anywhere in the Gem State (and Manitoba) this season to be aware of the detection and to only bring back deboned meat as well as only skulls, antlers and teeth that have had all soft tissue removed. Those restrictions are similar to measures in place regarding the importation of dead cervids from 26 other states and provinces where CWD occurs.

Sparking the move was the confirmation of CWD in two mule deer bucks that hunters harvested within a quarter mile of each other in Idaho Unit 14 near Riggins last month, Eric Barker of the Lewiston Tribune reported this morning.

The next nearest cases in free-roaming ungulates are well to the east and north, in the Dillon area of Southwest Montana and Libby area of Northwest Montana.

IDFG wildlife bureau chief Toby Boudreau told Northwest Sportsman his agency annually samples ungulates taken in units in close proximity to those and other CWD outbreaks and this year sent letters and sample collection bags to Unit 14 permit hunters.

“The Lower Salmon was on our rotation for increased sampling for those areas that are not intensively sampled annually,” he said.

Boudreau told Barker it was “awesome” that the voluntary hunter deer-lymph-node-collection program had worked so well, highlighting the key role sportsmen play in detecting and helping prevent the spread of the disease.

“Hunters were interested and engaged enough to learn how to do it, and then took the right samples and got them back to us in time and it worked perfectly,” Boudreau told the reporter.

The two infected deer were taken in the Slate Creek watershed, which drains into the Salmon River south of White Bird. Testing confirmed the presence of CWD in the animals on November 16 and both hunters were notified of the positive results.

All hunters who harvested deer or elk in Unit 14 – which stretches from Cottonwood and Grangeville in the north, down US 95 to Riggins in the south – are also now being encouraged to also have their kills tested, per Eli Francovich at the Spokane Spokesman-Review.

With CWD inexorably spreading across the West, IDFG has been sampling since the late 1990s but 2019’s discovery of the disease in whitetails in Northwest Montana spurred testing efforts in the Panhandle, where more than 1,100 deer, elk and moose were sampled last year and this year through midsummer, Francovich reported.

Further west, ODFW biologists were again collecting brain and lymph node tissues at Prineville and Celilo Park in Central Oregon this fall, and they’ve also been testing roadkilled deer and elk since salvaging became legal several years ago.

“We will continue to focus on our Idaho and Washington borders, the two known high-risk entry points, as well as continued road kill sampling from the salvage program of adult animals,” said Collin Gillin, chief ODFW veterinarian. “Additionally we are collecting from susceptible species throughout the state. Our northern hunt areas have been a focal zone for testing and our Idaho border now will garner increased scrutiny. Staff are presently discussing how we might add to the current effort, which can see about 2,0000 animals tested a year.”

Oregon also prohibits the importation of CWD-carrying parts such as “eyes, brains, spinal columns, lymph nodes, tonsils and spleens,” and also banned deer and elk urine-based scents early last year. In 2022 stopping at game checks becomes mandatory.

Meanwhile, WDFW this year boosted the number of whitetail check stations it operates in Northeast Washington during October’s general rifle and the ongoing late modern firearms buck seasons.

So far all hunter- and roadkilled whitetails have been negative for CWD, reported WDFW spokeswoman Staci Lehman in Spokane this morning.

The agency’s response to the threat is being guided by the recently drafted Chronic Wasting Disease Management Plan, which lays out monitoring and reactive measures.

With the disease now turning up some 40 air miles or so from Washington’s extreme southeast corner, Lehman said that WDFW plans, “dependent on funding, to expand our sampling efforts in 2022, most likely to Southeast Washington considering the proximity to the Idaho CWD detections.”

A 2021 state legislature proviso provided WDFW with $465,000 to survey for CWD in wild and captive deer herds.

Earlier this fall, agency ungulate specialist Melia DeVivo told me the hope is that early detection will allow managers to contain the disease and keep it from spreading. A study she did while at the University of Wyoming estimated that CWD shrunk the size of one deer herd by 19 percent every year and that in 41 years that population would go extinct.

CWD is caused by what are known as prions, described as “mutated proteins” that affect the brain and causes the animal to essentially degenerate as its neurological functions are destroyed.

“Symptoms in deer, elk, moose and caribou include excessive salivation, drooping head/ears, tremors, extremely low body weight, and unusual behavior, such as showing no fear of humans and lack of coordination. But CWD cannot be diagnosed strictly by symptoms because other diseases, or conditions, can also cause similar symptoms in an animal. Also, animals can be infected for months or years before showing symptoms,” IDFG reports.

One way the disease is spread is deer to deer via bodily fluids such as poop, pee, snot and spit.

“At this point we don’t know how it got there,” said IDFG’s Boudreau of the Riggins-area detection. “We are analyzing movement data at this very moment.”

DeVivo told me prions are “difficult to destroy,” as there’s just no good way to eliminate them from deer range at a scale that could begin to halt incidental transmission.

A second way the disease can be moved around is by people transporting the carcasses of infected deer, elk and moose from CWD areas to those where it’s not known to occur.

In late 2017, a Central Oregon man was cited for failing to follow his state’s rules on importing game from CWD states when he brought home a deer that was killed in Montana by a hunter. State biologists and troopers had to collect parts he’d disposed of improperly nearby after he butchered the carcass.

Hunters are advised to bone out their kills.

As for eating the meat of an infected animal, IDFG reports that the World Health Organization and Centers of Disease Control “have concluded that there is currently no evidence that CWD in deer and elk is transmitted to humans” but “as a safety precaution, both organizations as well as numerous state wildlife management agencies, recommend that no part or product of any animal with evidence of CWD or other transmissible spongiform encephalopathies should be fed to any species (human, domestic or captive animal).”

More information about CWD, including how to submit samples, is available on websites for IDFG, WDFW, ODFW (also see this ODFW page), USGS and the CWD Alliance.