More Details On NE WA Wolf Death Investigation: 4 Found In Feb.

More details are beginning to emerge about wolves found dead in Northeast Washington, the subject of an ongoing state investigation, but the information conduits will also raise eyebrows.

Washington Wildlife First claims that WDFW has been “dodging questions” about wolf poaching in the state and “sometimes outright lying to the public” in a press release following yesterday’s news about the case, first reported here.

The Seattle-based preservationist nonprofit – which has launched a reform campaign against WDFW, got the Governor’s Office to appoint friendly-to-its-viewpoint Fish and Wildlife Commissioners and attacked the agency in other ways – also posted an incident report from the Stevens County Sheriff’s Report that appears to document four dead wolves found during an Operation Stonegarden border patrol along Forest Service roads in the far north end of the county on Friday, February 18.

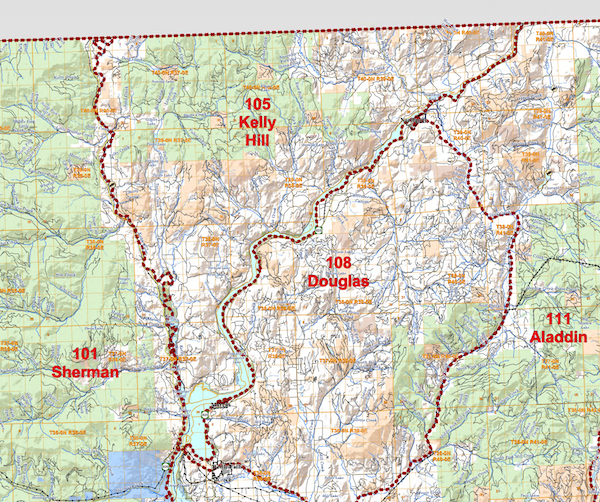

The eight-page report includes images of one gray- and three black-coated wolves lying atop snow in the Wedge, that triangular – and troublesome – piece of rugged, forested land between the Kettle and Columbia Rivers and Canadian border.

Officers estimated the first wolf they found had been there “for over three weeks,” and the other three, discovered on their ride back, appeared to be “more recent (guessing less than 2 weeks).”

“Officer Stearns and I at first thought maybe Fish & Wildlife had done a helicopter hunt to thin the numbers but there was no blood we could see or bullet holes … There were no new snowmobile tracks to indicate recent travel,” stated Deputy Henry Stroisch.

Stearns’ images show that hair had been plucked from the hides of three of the animals, presumably by scavengers, but apparently not the fourth. None of the photos appear to show blood in the snow. Midwinter was marked by an extended dry streak.

In a story posted late this morning, Eli Franovich of the Spokane Spokesman-Review reports that the Kettle Range Conservation Group of Republic claims the animals had been “poisoned,” but that a KRCG spokesman could not provide more details about the allegation “without implicating somebody.”

Eight wolves were poisoned in Northeast Oregon last year – including five in one group last February, an incident publicly revealed a month and a half later.

In their report, Stevens County deputies also write that upon returning to the office they informed Sheriff Brad Manke, who “contacted F&W to advised (sic) them and gave approximate locations” of the wolves, as well as passed along the cell phone number of one of the reporting officers, though it apparently wasn’t called by WDFW, according to the report, which is dated May 4, 2022.

Washington Wildlife First’s press release includes a quote from its executive director, Samantha Bruegger, who states, “The Department should be honest with the Washington public about what is happening to wolves in our state. The Department has been dodging questions on poaching for months, and sometimes lying outright to the public. The Department continually asks the members of the public to ‘trust’ it, but how can we trust an agency that has been so consistently dishonest with us?”

Hardcore wolf advocates frequently attempt to frame the Canis lupus population as frail, imperiled and in need of federal rather than state management, and this organization has also been trying to portray WDFW’s wolf and livestock conflict management as seriously inadequate, calling the agency “bought and paid for by special interests.”

The claims have been pushed back on by both WDFW wolf policy lead Julia Smith in presentations and heartfelt public comments and in a recent post by Conservation Northwest – far more pragmatic wolf advocates than WWF – that found from 2017 through 2021 Washington wolves had the lowest rate of human-caused mortality out of the five Northwest states where the species is either fully or partially federally delisted. CNW called Washington “the best place to live if you are a wolf in the western United States.”

The Fish and Wildlife Commission is currently in the middle of a debate about whether to pass binding, enforceable protocols around dealing with wolf-livestock conflicts, including lethal removals. During a May 13 meeting on the subject, Commissioner Melanie Rowland, a former federal attorney who appeared chummy with Bruegger at a recent commission retreat, tried to tie Stevens County wolf poaching rumors directly to the day’s discussion in pushing for court-litigable rules.

When Rowland was politely asked by Vice Chair Molly Linville, a Douglas County rancher who was running the meeting, if she could get with WDFW staff afterwards to answer that and other questions she had, Rowland flat out refused and a firm Linville was forced to move things along, noting that while Rowland’s statements were meaty they were also outside the scope of the day’s discussion and that at that point the citizen panel was already short on time. (A 10-year recreation plan initially on the agenda was scrubbed for a later date.) Linville reiterated soon afterwards that Rowland’s questions would be addressed outside of the commission with staff.

And during WDFW’s April 9 annual wolf count briefing, which presented continued good news for the state’s population, which grew by 16 percent and topped 200 for the first time, Commissioner Lorna Smith brought up “pretty persistent growing rumors about a fairly large-scale poaching operation” and numbers of dead wolves that were “a lot larger” than in the agency report in front of her. However, state wolf biologist Ben Maletzke pointed out that they were speaking specifically about 2021’s numbers, which only show two illegal kills, and he urged anyone with information on poaching to get in touch with agency officers.

WDFW’s monthly wolf reports for 2022 have listed only one known mortality this year, a 13-year-old Pend Oreille County female that died in late March of “natural causes.” But raising the Stevens County Sheriff’s Office report of the four found in February, Washington Wildlife First said in its press release WDFW has been “falsely claiming” to not know of any others.

Asked to respond to WWF’s allegations of “dodging questions” and “lying to the public,” Staci Lehman, a WDFW spokeswoman in Spokane this afternoon, stated, “Often, in order to avoid jeopardizing an active investigation, information is not released in order to prevent evidence destruction, protect officer safety, and ensure a case isn’t compromised. We want to collect enough information such that a solid case can be referred to a prosecutor. Without sufficient evidence, a conviction cannot be made.”

That makes Washington Wildlife First’s posting of the sheriff’s papers – not to mention Smith’s and Rowland’s public comments earlier this spring – potentially counterproductive and raises questions about their motivations.

As it stands, many things remain unclear in this case – are we sure the four dead wolves are even Washington animals or were actually killed in Stevens County and not, say, in Idaho and dumped?

What is crystal clear is that where the bodies were found is the absolute white-hottest point of the wolf front in the Evergreen State.

Over the last decade, Wedge Pack wolves have been associated with chronic depredations of a nearby ranch’s cattle, the near-full lethal removal of the pack by state sharpshooters, pack reformations due to the area’s excellent habitat and available prey, subsequent removals, wolf advocates’ campaign and threats against said producer, and a former Washington State University professor’s inflammatory statements about where the operation allegedly turned out its cattle.

WDFW’s 2021 wolf report states there were nine members in the Wedge Pack as of last December 31, with another having been poached last May. That animal was believed to have been the breeding female, but the pack’s numbers at the end of last year would suggest its loss wasn’t as catastrophic as initially feared by some.

That’s not to excuse poaching. The illegal killing of a wolf, a state endangered species, is punishable by penalties of $5,000 and/or a year in prison. WDFW asks anyone with information about the death or harassment of wolves to call the Enforcement Division hotline (877-933-9847).

The Wedge wolves weren’t involved in any confirmed depredations last year either, according to WDFW, though State Rep. Joel Kretz (R-Bodie Mountain) alleged that Northeast Washington ranchers aren’t reporting all attacks because they’ve “lost trust in the process.”

Earlier this week, WDFW mulled going lethal on the Togo Pack – to the west of the Wedge – after four confirmed and one probable calf depredations in 10 months, more than needed in the time span to consider taking out a wolf or two to head off further attacks, but Director Kelly Susewind “decided not to initiate lethal removal at this time.”

The agency said the rancher “has been in regular communication with WDFW staff, conducted carcass sanitation, removed sick or injured livestock when found, and has reported any suspected depredations,” as well as has checked on their cattle multiple times a day and will continue to regularly monitor them after turnout onto summer pastures soon.

Other nonlethal actions will be taken and encouraged.

Meanwhile, there’s a mystery around the lethal actions taken on four wolves.