Kretz County Wolf Delisting Bill Draws Feedback In Olympia

There was a lot of good feedback on a Northeast Washington wolf bill this morning, including strident support from a Democratic cosponsor who is the chair of the committee it’s in, boosting the odds that an amended version may move forward during this legislative session. And indeed, this evening it has been scheduled for an early vote on February 17.

As written, House Bill 1698 from Rep. Joel Kretz (R-Bodie Mountain) would establish a procedure for WDFW, counties and local tribes to manage wolves as if they were delisted from state endangered species protections when certain population benchmarks are reached locally and across Washington.

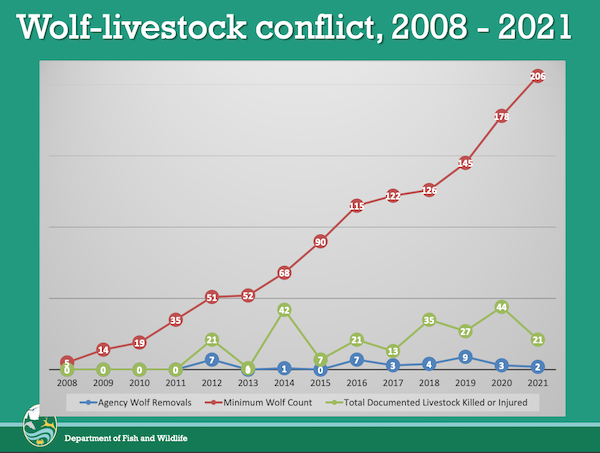

Kretz said colonization hasn’t gone as expected, leaving the state’s upper righthand corner particularly wolf-rich – 66 percent of Washington’s packs occur there – while an entire recovery region – the South Cascades and Northwest Coast Zone – is in “really sad shape” and nowhere close to having the four breeding pairs for three straight years (currently, there are only two known wolves in that zone) that are required under WDFW’s 2011 wolf management plan for delisting to be considered by the Fish and Wildlife Commission.

“My concern is, we’re going to wait another 10 to 15 years to get the magic numbers in the magic places,” Kretz told the House Agriculture and Natural Resources Committee during a public hearing aired on TVW.

So under his plan, once there were 15 breeding pairs across the state for three straight years – there were 19 at the end of 2021, and probably will be that many in 2022 and 2023 – and three in a county, that county’s commissioners could notify WDFW that gray wolves no longer meet state ESA designations there, WDFW will double check that and then develop a management plan with the county and tribes within its borders, as well as local law enforcement.

The bill would essentially recognize the “really good job” done in Northeast Washington recovering wolves, as well the “huge strain” it has placed on the local community and ranchers, Kretz said. He said it could allow for “better coordination” with locals on management, and cited an advanced GPS collar used by the Stevens County Sheriff’s Office that could put wolf location data in the hands of range riders closer to real time than those currently used with a 24-hour delay.

Managing wolves in a responsible way with WDFW and the tribes was something Stevens County Commissioner Wes McCart said he was willing to step up and do.

But an official at the Governor’s Office was hitting the brakes on the whole idea.

Ruth Musgrave, senior natural resources policy advisor for Governor Jay Inslee, said the bill undermined the authority of WDFW and the Fish and Wildlife Commission to manage wolves as a state-listed species, calling it “far reaching and damaging.” Given that protected species can only be delisted at a statewide level, not regionally, she said the bill could set a precedent for doing so.

That drew responses from Rep. Larry Springer (D-Kirkland) and Rep. Ed Orcutt (R-Kalama), who pointed out the state is already divided into different management regions and some species are managed at the game management unit or watershed level.

WDFW’s Eric Gardner interjected to note that’s because those species have different classifications – mule deer, say, are game, while wolves are endangered, and endangered and threatened listings are done on a statewide basis.

Gardner said he appreciated and supported Kretz’s opening remarks in support of his bill, but overall WDFW was against it because in part it doesn’t spell out what wolves would be classified as in any delisted counties.

“This is important because specific management actions and laws that authorize take, and penalties for unlawful take, are directly tied to the classification of species,” he said.

If they were unclassified, they could be subject to unregulated hunting, Gardner added, which could prolong their recovery timeline – “even prevent it from happening.”

While Gardner was quick to add that he didn’t believe that that was what Kretz et al were getting at, some apparently are taking that ball and running with it.

A Washington Wildlife First email alert describes HB 1698 as “a thinly disguised wolf-hunting bill.”

Rep. Mike Chapman (D-Port Angeles), who chairs the House AGNR Committee, said he’s been called all kinds of things over this supposed “wolf-killing bill” he is cosponsoring with three fellow Democrats and four Republicans. He read straight from the bill about how it would set up comanagement after delisting and stated there was nothing about shooting wolves dead in it.

“This is good policy. This is not setting up the killing fields part two,” a visibly annoyed Chapman stated. “I’m frustrated that this is being viewed as open season when really we’re setting up a framework where a local county can petition their state government and say, ‘Hey, maybe things aren’t as they seem. We’d like to work with you. We’d like the tribes to be part of the process. We would like to collaborate to find solutions that work on the ground’ … This is the kind of policy that we want to see from folks working with state government to find a solution on the ground.”

Among those who would aid in comanagement of wolves at a local level was Jarred-Michael Erickson, a Colville Confederated Tribes wildlife biologist who is now the tribal Business Council’s chairman. He stated that wildlife on his reservation is managed for big game, which are increasing, because they’re a subsistence tribe, but they also never want to see wolves extirpated again.

He was asked by Chapman about something Musgrave, the governor’s advisor, had said earlier in the meeting – “It seems that they’re not dispersing like wolves usually do in part, because, you know, they’re getting hunted on the Colville Reservation,” Musgrave had said, adding, “and the Teanaway Pack, for example, is completely isolated and so now it’s down to one wolf.”

“That’s a false statement,” Erickson said of tribal wolf hunting affecting statewide recovery.

Wolf season, he said, is open year-round “and we really haven’t put a dent in the population.” He said “quite a few” have been taken on the reservation and a “decent number” on the North Half, those federal, public and private lands to the north around Republic, Curlew and Chesaw.

GPS collar data shows Washington wolves tend to move on their own every which way but towards the South Cascades. As for the Teanaway wolves Musgrave mentioned, no doubt I-90 has limited dispersal southward, but that pack was also woefully inbred, with its longtime alpha male breeding its sister and then two of their pups over the years.

But speaking against the bill, Carter Niemeyer, the retired federal wolfer and wolf manager who helped the Colvilles capture and collar their first wolves, termed those in Northeast Washington critical for recovery elsewhere in the state.

Mentioning the Klickitat County Sheriff’s Office’s cougar removals in the name of public safety, Samantha Bruegger of Washington Wildlife First said it was imperative wolves be managed by the state rather than heavy-handed locals.

Zoe Hanley of Defenders of Wildlife said counties weren’t a biologically relevant scale for wolf recovery and managing them that way would diverge from accepted standards, and the bill amounted to a “call to kill more wolves faster.”

And David Linn, a very frequent flyer on the wolf comment circuit, stated that the way it’s written, three border-straddling breeding pairs could satisfy requirements for two different counties.

Others against it noted that WDFW and the Fish and Wildlife Commission are already in the midst of a periodic status review of gray wolves, in coordination with University of Washington researchers, where they said the matter should be handled. The review is expected to be out in April or May, according to Commissioner Lorna Smith of Port Townsend, who was on hand to voice her personal support for WDFW’s position against the bill.

On the flip side, former Fish and Wildlife Commissioner Jay Holzmiller, speaking for the Washington Cattlemen’s Association, brought up how bottom-up direction from former Governor Locke led to his county’s Asotin Creek, home to two ESA-listed fish stocks, becoming the state’s first model watershed. Why couldn’t wolf management be structured like that, he wondered.

George Wishon called in from the cab of one of his Stevens County ranch’s rigs in support of the bill, saying it would provide for faster responses and better local coordination. Asked by Kretz about losses to wolves, he said he and his folks’ operations have had 150 cattle killed or injured over the past 10 years.

“The wolf population in Northeast Washington is very healthy because they’ve eaten a lot of very good beef,” Wishon said.

Officially, WDFW stats show about 250 confirmed livestock depredations statewide over the past decade, mostly in Northeast and Southeast Washington, and the agency has noted how other states’ wolf managers have asked how it keeps losses so relatively low.

While opponents feel that Kretz and Northeast Washington are trying to undeservedly take credit for wolf recovery – Washington Wildlife First said the bill “falsely celebrates ‘wolf recovery'”; Linn said counties touting doing so “turns the facts on their head” – Paula Swedeen of Conservation Northwest shared how CNW’s early efforts around range riding to ward off local wolf-livestock conflicts had been met with skepticism and said she would never have dreamed how widely accepted it is now, with some 30 riders working for her organization and a local one, plus more signed up through WDFW.

Swedeen said that the success being seen in Northeast Washington wasn’t possible without local buy-in, and – having signed in on the bill as “other” – added that she was willing to work with the sponsors on the bill.

Kretz was all ears for that, he told his “skeptical partner.” He felt that the bill was pretty clear, but he was willing to clear up language that was giving folks pause.

“I’ve spent the last 10 years going home and telling them, ‘We’re not making any progress, we’re not making any progress,’ and what I told them this year is I’m going to take the smallest, littlest, tiniest approach I can possibly take. And I think that’s what this bill is. I’m really disappointed at some of the reactions to it … To hear the interpretations is really discouraging to me,” Kretz said.

One interpretation from today that should buoy him was that of Rep. Springer.

After Committee Vice Chair Rep. Kristine Reeves (D-Federal Way) read into the record that 998 people had signed in con, 129 pro and six other, Springer observed that the “overwhelmingly vast majority” of those against it were from Western Washington or from outside the state and “don’t live anywhere near the problem.”

It’s one thing to hear that from an Eastside conservative or Westside Republican; it’s quite another for someone from the other side of the aisle, let alone the shores of Lake Washington, to voice it.

For what it’s worth, as Rep. Springer stated.