Inslee Lays Out 2023-25 WDFW Budget, Salmon Proposals

Governor Jay Inslee’s proposed 2023-25 budgets would “solidify” WDFW funding with an $88 million increase for operations and a $190 million, largest-ever, boost to capital projects, according to a message sent out to staffers yesterday.

“Overall, this budget proposal funds ongoing work and obligations and is an increase to WDFW’s capacity,” stated Morgan Stinson, chief financial officer for the 1,900-employee, million-plus-acre fish and wildlife management agency.

But it also does not fund WDFW’s $47.6 million biodiversity restoration request due to “insufficient revenue,” he added.

“Given the priority of this work, we will explore options with the legislature regarding how they might approach funding this priority,” Stinson told fellow employees.

His email to them also shows the governor declined requests such as $1.4 million for ESA permitting work that would benefit salmon anglers in Columbia tribs during seasons of strong returns, $3.1 million to evaluate emerging commercial fishery gear on the big river, and $644,000 to monitor wildlife diseases such as avian influenza, which is currently killing waterfowl and other North Sound birds this fall.

Inslee’s state budget, rolled out Wednesday, will be followed by proposals from House and Senate lawmakers, and they all will be debated during the upcoming long session of the legislature before a final spending package for the July 2023-June 2025 budget biennium emerges in April or later, if added extra time is required.

(Sorry, in full-on World Cup mode.)

Among the topline items is “the strongest suite of budget and policy initiatives in Washington’s history to help protect and restore vital salmon habitat and restore salmon populations,” according to a pitch sheet from Governor’s Office.

“His budget includes funding to promote the highest priority actions in the governor’s Salmon Strategy that also align with known tribal priorities and regional salmon recovery plans,” a statement on Inslee’s Medium blog says.

Following on last year’s doomed Lorraine Loomis Act, this new effort tallies $872 million, with the lion’s share of that – $502 million – designated for habitat restoration on “working lands,” riparian areas and “voluntary protection and restoration” programs, with funding distributed to not only WDFW but DNR, DOE, the Recreation and Conservation Office and other entities.

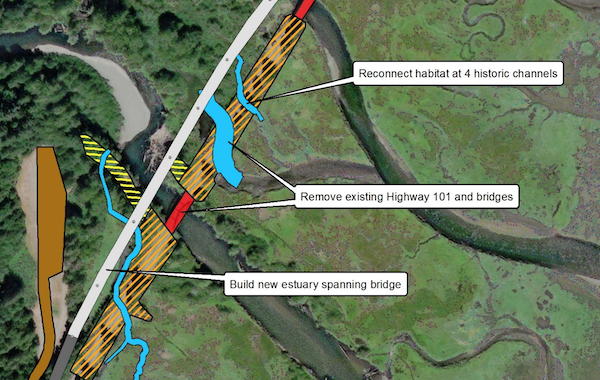

Among the big-ticket items is the $41 million Duckabush project to elevate Highway 101 above the east Olympic Peninsula river’s estuary to reconnect it to the floodplain and improve fish habitat.

Another $94.4 million would go toward replacing or modifying fish passage barriers so salmon could access more habitat, including $17.3 million to upgrade the Toutle River fish collection facility, which helps coho and steelhead get past the Mt. St. Helens sediment dam.

On the hatchery front, there’s $12 million to design and permit a new Chinook production center on the Deschutes River near Olympia, which theoretically would benefit up-Sound anglers and southern residents alike, $17.2 million to replace intakes and ponds at Wallace River, where summer Chinook, coho, steelhead and now chums are being reared, $38 million and $18.5 million to renovate the Spokane and Naselle Hatcheries, along with funding for Beaver Creek on the Elochoman, Soos Creek and Palmer Ponds on the Duwamish-Green, and Kalama Falls.

There’s also $1.5 million for ongoing sea lion management in the Columbia River, where WDFW along with other Northwest states and tribes have lethally removed 52 Stellers and 36 Californias at Bonneville Dam since October 2020 under a new permit to reduce pinniped predation on ESA-listed salmon, steelhead and other stocks in the Columbia system, and $940,000 to study marine mammal diets in Puget Sound and nearby saltwater arms and “identify nonlethal actions to deter them from eating salmon and steelhead.”

Speaking of marine mammals and diets, some $3.6 million would be provided to “install and assess a near-term solution to reduce juvenile steelhead mortality” at the Hood Canal Bridge, a chokepoint for outmigrating smolts and where 50 percent die due to predation from harbor seals, etc., as they struggle to figure out how to get around the 1.4-mile-long mostly on-water crossing.

Speaking of manmade obstacles, $10 million would go toward analyzing how to replace electricity generation and barge transportation should the lower four Snake River dams be breached. Inslee and US Senator Patty Murray concluded the dams’ services and benefits need to be replaced or mitigated before they’re decommissioned.

(“That amount could increase funding for the Salmon Recovery Funding Board by 25%,” tweeted Todd Myers of the Washington Policy Center.)

And just over $5 million would go towards better salmon harvest management, including $2.7 million for more game wardens to “increase fishery compliance since officers are encountering more recreational harvesters than ever before and” – do not shoot the messenger here, I’m merely transcribing the Governor’s Office’s rather jaw-dropping allegation – “find that many take more salmon than allowed.”

Where WDFW requested nearly $10 million for expanded wildlife conflict response work, Inslee’s budget would fund only $1.5 million. Similarly, $6 million to modify the popular but “deteriorating” Tucannon Lakes as part of floodplain improvements there was pared back to $1 million.

But the governor would fully fund the agency’s climate-resiliency and carbon-neutrality efforts, pegged at $5.3 million and $1.7 million, respectively. WDFW summarized the former as: “increases capacity to continue to fulfill key aspects of our mission vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, including guiding recovery efforts for at-risk fish and wildlife species, providing harvest and recreation opportunities, providing technical assistance, permitting, and planning support to a broad array of stakeholders, and managing agency-owned lands and supporting infrastructure.” As for the latter, it would “catalyze transition of the Department’s fleet to electric vehicles and alternative fuels,” etc.

Payment in lieu of taxes to counties for the land WDFW owns would also be increased from $4 million to $4.5 million, according to CFO Stinson.

Again, all of this budget proposal stuff is subject to state lawmakers’ sausage making over the coming months – including whether they fold in WDFW’s coastal steelhead proviso request for $5.9 million mostly for fishery monitoring and management – and which the Olympia Outsider™ will attempt to cover.

One item that ol’ Oly Outs pointed out to me this morning on WDFW’s failed biodiversity request front is that the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act is active in Congress as the end of the year draws nigh. It could provide WDFW (and other state and tribal managers) with millions annually for mostly nongame but also some imperiled game species alike. Early last year the agency’s Nate Pamplin called the bill a “game changer” because at the time WDFW’s budget only covered 5 percent of the funding needed to “adequately conserve” some 270 species most in need of help in state wildlife action plans.

(Yesterday also saw the announcement of some $40 million in federally recommended fish passage/habitat improvements on the coast and Snohomish system, dam removal feasibility studies on the West Fork Hoquiam and Similkameen Rivers and removal of the Bateman Island Causeway at the mouth of the Yakima River.)

Anyway, back to Washington, besides development of WDFW’s capital and operating budgets, there will be any number of fish- and wildlife-related bills to watch this legislative session. So far nothing that state representatives and senators have prefiled has been too alarming, but in the meanwhile the agency has some priorities it hopes lawmakers will introduce.

Probably the most notable proposed legislation – at least in terms of how long I went on it last June, when it came before the Fish and Wildlife Commission – is requiring smelt dippers, carp anglers and crawfish catchers to purchase a fishing license, just as is required for other fish and shellfish, whether you’re harvesting for the table or catching and releasing. Right now, the three species are exempt by state law from license requirements.

“Licenses are a gateway to knowing the rules and regulations for fisheries in Washington state,” WDFW argues. “Part of the licensing process requires participants to read the annual fishing pamphlet and abide by the rules when fishing which helps maintain more orderly fisheries.”

The primary example they will bring up was last March’s lower Cowlitz smelt dip, in which 70 percent of those who were cited by officers for going over the 10-pound individual daily limit “did not have a fishing license.”

As for carp, “Enforcement officers have had trouble monitoring illegal salmon and steelhead fishing in certain locations – as the individual claims they were fishing for ‘carp’. Requiring a license will make that person aware of the rules for taking both carp and other fish.”

WDFW is also looking for bills to: help ease the cost of removing shoreline armoring from private property; expand signage directing traveling hunters and anglers to voluntary fish, wildlife and aquatic disease checkpoints; and address permitting for “routine” in-water work by WDFW.