Fish And Wildlife Comm’s Baker, Smith Go Before Senators

More Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission members sat down before lawmakers this afternoon to talk about their backgrounds, interest in overseeing WDFW policies, and take questions from state senators.

Barbara Baker of Olympia and Lorna Smith of Port Townsend were the latest two to appear before the Senate Agriculture, Water, Natural Resources & Parks Committee, after six fellow members received do-confirm recommendation votes last week.

For Baker, an attorney and retired chief clerk of the state House of Representatives, it was essentially a voluntary exercise, as she has already been confirmed by the full Senate, but it also offered a glimpse into the mind of the person “widely viewed as the foundation of the commission,” according to Sen. Kevin Van De Wege (D-Sequim), who chairs the senate committee.

“If everybody else makes themselves available, I should as well,” Baker told legislators.

As such, she faced similar questions to the others, including one from Sen. Judy Warnick (R-Moses Lake), who in previous hearings noted that members of her family are sportsmen, and so she wanted to know what Baker was doing to continue to provide hunting and fishing opportunities – as well as increase them.

“Right now, we have so little truly wild areas left that we don’t need to be recruiting or retaining anybody to go out there,” Baker bluntly responded.

While she prefaced that statement by saying she was speaking for herself and not the commission, it was still a jarring line for the chair of the Fish and Wildlife Commission – tasked by the legislature “to maximize the public recreational game fishing and hunting opportunities of all citizens” – to utter, especially at a time of diminishing Washington hunter and angler numbers impacting WDFW budgets and forcing more reliance on the General Fund (which she’s made a pitch for with the director). Last year, WDFW convened a huge set of stakeholders, including the editor of this opportunity-based magazine, and came up with a big recruitment, retention and reactivation plan to boost participation and revenues from license sales, and thus also support for conservation.

“I think the limiting factor isn’t the license fees that’s been talked about,” Baker added about the cost of deer tags, etc., a perennial hot button even if prices haven’t been raised in a veritable eon. “I think it’s the lack of game in this state. And I think that has a lot to do with the number of people in this state and the increasing number of people, which essentially causes sprawl.”

Even as the statement will give WDFW’s increasingly busy marketing department a headache, there is some unfortunate truth to it.

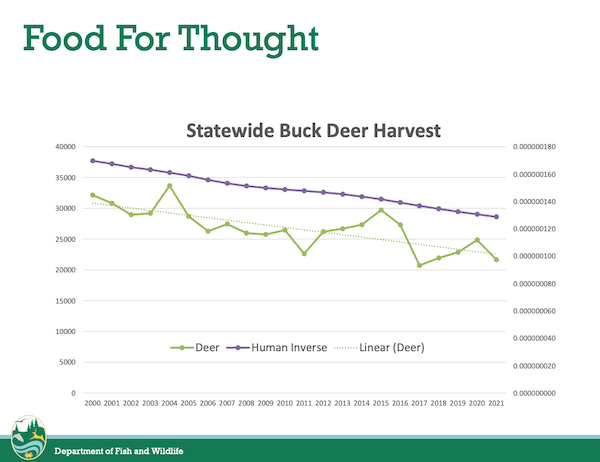

Baker pointed to a late January WDFW presentation to the commission on the status, trends and limiting factors around the state’s deer and elk, which in part show buck and bull harvest declining this millennium at a rate not unlike human population growth if you were to express the latter as an inverse.

In particular, she called out a slide that stated that for every three Washington hunters and for every 127 Evergreen State residents there is one elk, whereas states like Wyoming offer one hunter and five people per elk, Montana two and seven, Idaho two and 15. WDFW often points out Washington is the second smallest Western state with the second highest population.

During that January presentation, Kyle Garrison, WDFW Ungulate Section manager, identifed “human encroachment on our wildlife populations in the state, and that certainly does play a role in the amount of habitat that is available to elk,” which impacts population levels.

However, the vast majority of hunters prefer lands other than Baker’s “truly wild areas” because they’re far more productive and accessible than remote wilderness, and some will point to predation as the real problem. Studies in the Blue Mountains show cougars are keeping elk from rebounding to former levels, so the commission voted 5-4 to allow hunters to tag a second lion there, with Baker dissenting. (Only one of the three zones has been closed this winter because it reached its quota).

“So when people go out now,” Baker said, “what we hear a lot from hunters is, ‘There’s nothing left. I can’t get, you know, mule deer or an elk, I can’t get any, I don’t even see them.’ And so we need to look at that. Now, their solutions aren’t always the same … I think there are other solutions besides killing carnivores. And those are the things that we’re trying to work through.”

Some claim the commission has become anti-hunting, but Baker told senators she disagrees.

“We are not anti-hunting. Matter of fact, if I was to think about it, I can’t think of anything the commission has done … I don’t think we have slowed down or discredited or discouraged hunting in any way. In fact, I think the opposite is true,” she stated.

The commission has certainly discouraged the hunting of bruins this time of year, passing a policy last November that specifically “does not approve recreational hunting of black bears in the spring,” discrediting a decades-long limited-entry opportunity in the process. While it left the door open for “management hunts” and last Saturday former Commissioner Kim Thorburn urged her colleagues to put forth a proposal, members denied three more petitions to begin rulemaking over the weekend.

With Thorburn’s recent departure after eight years, Baker is now the longest-serving commissioner, having been appointed in January 2017.

As for Lorna Smith, the word “coalition” was peppered throughout her introduction detailing her family’s history as lighthouse keepers, working for Snohomish County on environmental issues and on various WDFW-related advisory groups, including a failed mid-1980s campaign to increase General Fund revenues to the agency. She considers herself to be “approachable” and glad to talk to anybody and said that volunteering is “in my blood.” With fish and wildlife, “it’s so much about habitat and preserving the habitat, so we focused on that,” she said about building coalitions.

In response to a question from Sen. Jesse Salomon (D-Shoreline) on what might be done with gillnet impacts on ESA-listed Columbia salmon, Smith said there was “a lot of concern about wild fish conservation” on the commission and said she’d been very impressed with the Wild Fish Conservancy’s pound net project on the lower river.

Baker spoke to the complexity of managing the system and the need for concurrency with Oregon, and said that even those who are anti-gillnet know there is still a need for the gear in the SAFE areas – downstream off-channel bays – to keep up production for commercial and sport fleets and southern resident killer whales.

Next up before senators is Steven Parker, the retired fisheries biologist who worked for the Yakama Nation for decades before being appointed to the commission by the Governor’s Office earlier this month. He’s due Thursday afternoon.

Afterwards, presumably, the senate committee will hold a do-confirm recommendation vote on Smith and Parker – again, Baker’s already confirmed. It will be interesting to see how the vote on Smith goes. She’s a controversial member of the commission and attracts quite a bit of lightning, but last week saw only one senator object to Melanie Rowland, a similar firebrand, surprising some hunting observers who follow such things. Last year Smith received a partisan 4-3 recommendation.

As it stands, commissioners can still serve on the Fish and Wildlife Commission even if not confirmed by the full Senate.

Correction: An earlier version of this blog incorrectly interpreted Barbara Baker’s remarks around gillnetting as her being anti-gillnetting as she spoke to anti-gillnetting Sen. Jesse Salomon on SAFE areas.