DFWs Recommend No Lower Columbia Sturgeon Retention In 2024 As Decline Continues

It’s getting worse and worse for sturgeon in the Lower Columbia, where in all likelihood there will again be no harvest opportunities this year.

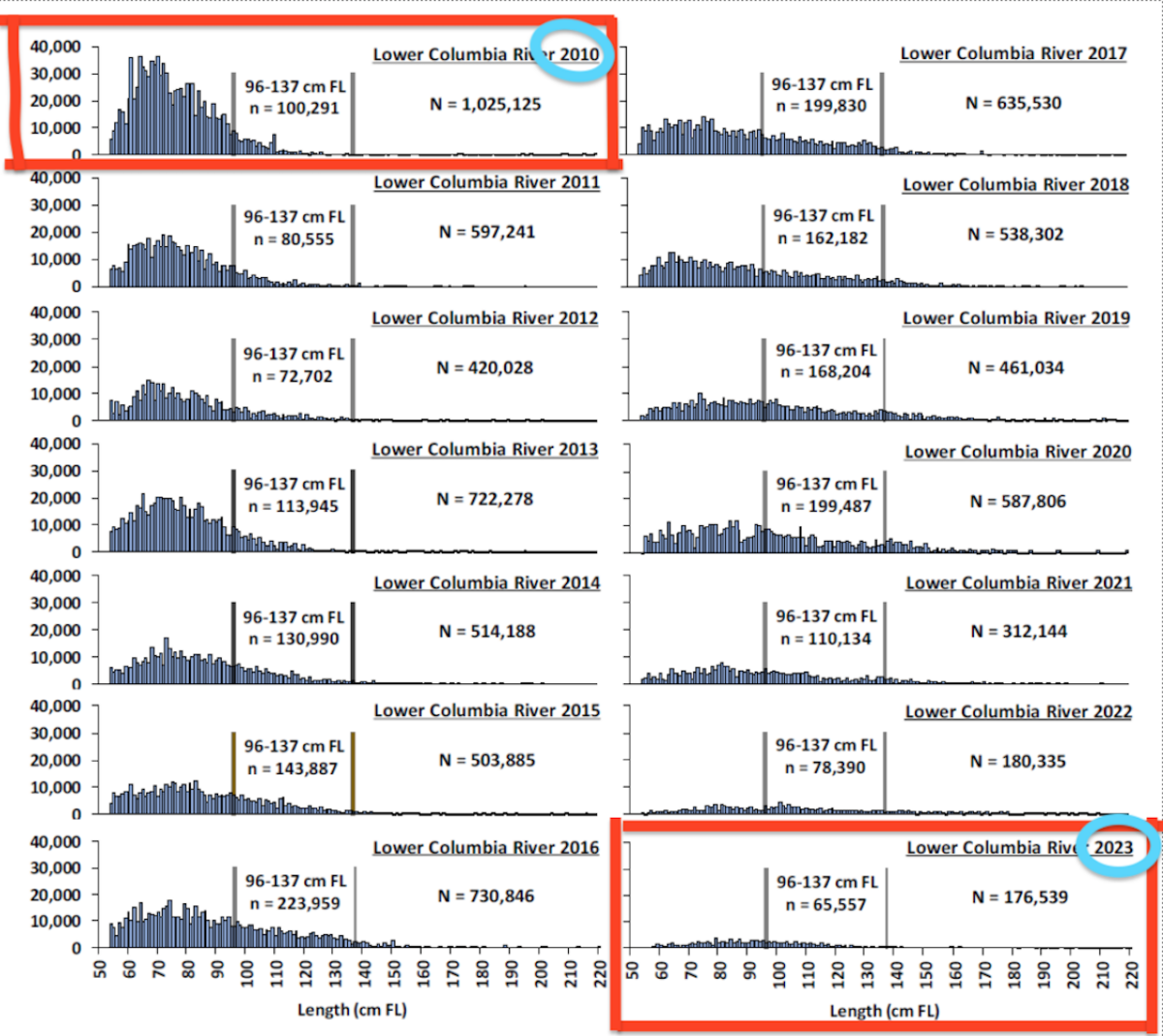

State managers from both sides of the big river estimate that last year saw the fewest “legal-size” sturgeon between Buoy 10 and Bonneville Dam since at least 2010, just 65,557 fish between 38 and 54 inches fork length, as predation and other factors appear to be limiting the ability of the population to build itself back up.

“While data supports the conclusion that the population could support limited harvest, it continues to be difficult to prosecute retention fisheries with meaningful harvest opportunity given the legal-size abundance,” an update out from ODFW and WDFW Friday afternoon states. “Therefore, joint state staff will not recommend retention of white sturgeon for either commercial or recreational fisheries downstream of Bonneville Dam again in 2024.”

The last sport retention opportunity here was three days in September 2022, from the Wauna powerlines up to the dam. Catch-and-release fisheries will stay open this year; mind the spawning sanctuaries and closures below Bonneville and Willamette Falls.

Where in 2010 there were at least 900,000 juveniles – fish between 21 and 38 inches – last year’s survey estimate found not even a tenth as many, just 84,600.

And overall sturgeon numbers below the dam have now declined by nearly 83 percent since 2010, from an estimated 1.025 million of all sizes then to just 176,539 last year.

River conditions and other factors likely influence abundance and estimates, but the trends clearly show the problem: The Lower Columbia is producing fewer and fewer sturgeon to age.

“A low juvenile abundance means fewer fish are available to grow into the legal-size range and directly impacts the legal-size abundance. This has resulted in fewer available fish available for harvest,” the DFWs note.

It is concerning in terms of future spawners, though at the moment adult numbers are “well above” a 3,900-fish conservation-status threshold in an Oregon management plan.

“This indicates that a sufficient recruitment potential is available within the population to rebuild the shortfall in juvenile abundance. However, ongoing issues within the ecosystem continue to constrain recruitment and limit Age-0 fish survival,” state managers say.

So what’s the deal?

Last February, when I essentially reported this exact same story, a WDFW biologist told me that “pinnipeds are one major concern, directly through predation on sturgeon and indirectly by changing spawning sturgeon behaviors to avoid predation and either not spawn or spawn somewhere less suitable for eggs/larvae to survive.”

Steller sea lions preferentially target sturgeon. Congress granted Northwest fishery managers an exemption to the overly protective Marine Mammal Protection Act to begin lethally removing some of the animals, but the facilities to take them out are still only in place at Bonneville Dam and below Willamette Falls.

So far, just 78 have been removed.

But sea lions are far from the only issues affecting Lower Columbia sturgeon.

Other constraints “include things such as climate change and hydrosystem operations affecting the timing and magnitude of temperature and flow in the spawning grounds, changes in the availability of sturgeon prey (i.e., other fish and shellfish), a lagging effect from previous decades of harvest, contaminants affecting reproductive potential in spawning adults, etc.,” the biologist told me.

All together, it paints a bleaker and bleaker picture for a fishery that as late as the late 1990s saw anglers keep over 50,000 sturgeon annually in the Lower Columbia, and a population that was an important foodstuff in late winter for Chinookan peoples in days of yore.

If there’s other good news, it’s that even after juvenile sturgeon numbers fell into “conservation status” from 2013 through 2015, leading managers to close all harvest – sport and commercial – from 2014 through 2016, the population did bounce back to “desired status” from 2019 through 2022.

That shows resiliency and provided some harvest opportunities.

But the population has since dipped back into a between-statuses zone, and the trend – given declining numbers of legal-size fish that eventually matriculate into breeders – is not that great.

One wonders how long before the C&R fishery is axed or someone proposes to list Lower Columbia white sturgeon as a federally threatened or endangered stock.