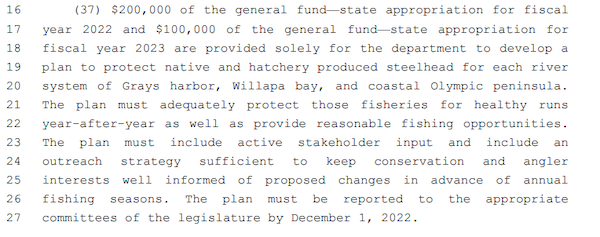

Concerns Around WDFW’s Draft Coastal Steelhead Proviso Plan

It’s not the lightest reading of all time, but some anglers dogged enough to dive into WDFW’s draft Coastal Steelhead Proviso Implementation Plan are expressing concerns about it, particularly elements centered around hatchery production and sport and tribal fisheries.

They’re confused by “new and hard to understand terms” in the 138-page plan that was recently rolled out for a compressed 10-day public comment period, and worry its approach “could see WDFW significantly reduce or even eliminate hatchery steelhead production in a large segment of coastal areas in near future.”

Then there’s how it meshes with the Statewide Steelhead Management Plan and its call for collaborative processes as well as the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission’s hatchery policy, the amount of tribal input it did or did not see or whether it will even fly with the comanagers, and if in the end it will save wild winter-runs.

That’s not to say the legislatively mandated CSPIP is all worrisome – even those outside critics liked some of its elements, such as better creel sampling, closer watershed-by-watershed management, and its attention to Washington’s crown jewel fish and fishery without all that comes with an ESA listing (a long-rumored petition was filed with federal overseers in August to list OlyPen fish).

But they also worry that the future of steelheading – hatchery and wild – on Grays Harbor and Willapa Bay rivers is at stake.

Those are some of the concerns of reviewers as they took up WDFW Fish Program director Kelly Cunningham’s Nov. 10 request to “dig in to the draft plan and share their perspectives” on a future path that the agency says it “designed … to provide sustainable fishing opportunities, protect coastal steelhead, and incorporate stakeholder input and outreach.”

Its Ad-Hoc Coastal Steelhead Advisory Group provided initial feedback over the past year.

Away from that circle, Ron Garner, in comments representing the Puget Sound Anglers State Board and Steelhead Trout Club, expresses confusion about some of the plan’s highfalutin and nebulous terms – “’Transitional Hatchery Equilibrium Protocol’ seems like a smoke screen for unjustified actions” – and says its processes are not clear about what would happen to state and tribal fisheries and hatchery production under certain scenarios.

“On the surface, it is easy to believe the impacts would be severe resulting in significant hatchery production cuts in the Chehalis Basin and the curtailing if not eliminating reasonable sport fishing opportunities,” Garner writes.

Brian McLachlan, who has been closely following WDFW’s coastal winter steelhead season-setting process in recent years, expedited his lengthy comments by sending them in draft form so as to get his perspective to the Fish and Wildlife Commission’s Fish Committee ahead of members’ meeting tomorrow on CSPIP. He took a deep dive into what he calls the plan’s “‘cut hatcheries first’ approach,” a rescaling of smolt releases based on modeling in a white paper from WDFW’s Hatchery Evaluation and Assessment Team.

Essentially, HEAT’s multiyear analysis recommended reducing stocking on the coast by 29 percent, or 262,000 smolts – mostly summer- and winter-runs released into the Wynoochee but also zeroing out releases in the North, and reducing them on the Skookumchuck and Naselle among others – to meet SSMP goals for reducing the percentage of hatchery fish spawning in the wild. Of note, HEAT also identified maximum release figures that in some cases are above current levels, if hatchery practices were to improve.

(For more on the HEAT recommendations, quietly released by WDFW in August, see this Wild Steelheaders United blog; for his part, the agency’s Cunningham acknowledged the report but also noted “it is important to consider other factors in the agency’s decision-making process relative to managing hatchery programs, such as standing commitments with tribal co-managers, mitigation agreements, legal obligations, socio-economic considerations, and others.”)

McLachlan also calls out a CSPIP element dubbed “regime classification” and the aforementioned Hatchery Equilibrium Protocol. Wild populations would be categorized on three levels – think red light, yellow light, green light and all that entails – and hatchery production on the same systems would be subject to a protocol gauged to native returns over the prior five-year period.

He says that if you applied this framework to, say, the South Coast where wild runs have been under escapement goals in recent years, the plan “could effectively end WDFW production of hatchery steelhead for fishing in all of Grays Harbor and Willapa Bay in the very near future.”

And with those particular systems’ wild stocks struggling and available fishery impacts under SSMP very thin, “could WDFW’s draft Proviso Plan not mean the end of steelhead fishing in these areas?”

What’s more, it may result in a “logistical nightmare” to restart hatchery production when wild fish bounce back, with long lapses between consumptive fishery seasons.

“For example,” McLachlan writes, “if a wild steelhead population is under its escapement goal for 3 consecutive years, as is common during low ocean survival down cycles, the HEP would kick in to severely reduce or entirely eliminate smolt plants. Then, if the down cycle ends, and the wild run rebounds to above escapement goal levels, as they have in the past, it would take at minimum 3 consecutive years of above escapement goal returns to satisfy the 3 out of 5 criteria, and perhaps another year (because post-season wild run size reconstructions are often delayed a few months) for smolt plants to resume at fishable levels. And that’s assuming the agency has enough money, staff, and smolts on hand and isn’t using the hatchery facility for a different program. And then it takes another two winters for the predominately 2-salt hatchery steelhead to return. Thus, there could be a minimum 5-6 year gap in returns of fishable numbers of hatchery fish, and this gap would occur during the up-cycle of wild fish. Then, after 5-6 good years, if a down cycle returns for wild fish, fishable numbers of hatchery fish would be returning at the same time; however, fisheries targeting hatchery fish could be restricted due to potential impacts to wild fish, like we’ve seen the last few years. That, to me, is like a dog doing circles chasing its tail.”

Those aren’t all the concerns the two anglers had – my brain is full tonight and it needs a rest – but their comments amount to a signal to the Fish and Wildlife Commission that for some the draft Coastal Steelhead Proviso Implementation Plan may not be ready for prime time.

Garner, the PSA and STC representative, called on WDFW and the commission to seek an extension from lawmakers on its submittal.

But at the same time it also represents a $5.9 million ask, a contract, to lawmakers this next session – WDFW wants to implement CSPIP in the July 2023-July 2025 budget biennium – and failure to score that funding could, agency steelhead managers yesterday stated, impact fisheries, slow development of those local-basin steelhead management plans and hinder fish research.

Thursday’s Fish Committee meeting on the draft proviso plan and other coastal steelhead matters begins at 8:30 a.m. and will be carried on TVW and via Zoom.