Comment Open On NMFS Hatchery Chinook Increase Program For SRKWs

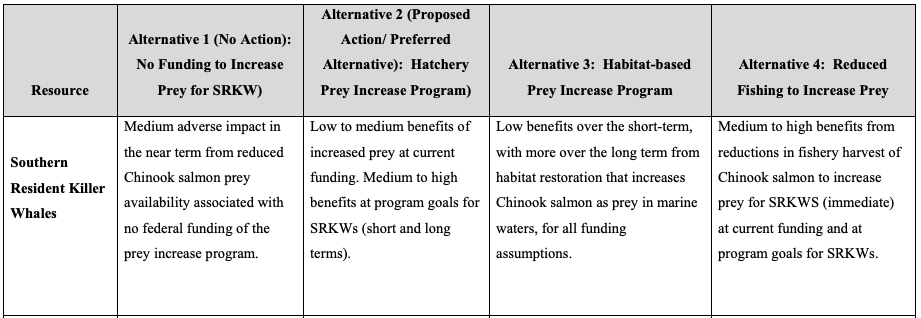

Continuing a federal prey increase program that’s been providing more hatchery Chinook for starving southern resident killer whales will have “medium to high benefits” for the Northwest’s iconic marine mammals over the short and long term.

That’s according to a court-ordered draft programmatic environmental impact statement now out for public comment from the National Marine Fisheries Service.

NMFS wants to keep funding the $6.2 million federal effort that has increased salmon production at a number of WDFW, ODFW, USFWS and tribal hatcheries in Puget Sound, Columbia Gorge, Upper Columbia and Snake River since 2020, including 8.3 million smolts last year and as many as 11.75 million additional fish anticipated to be released this year.

“Salmon increased as much as 3 percent in the places and times where the whales can best access them,” the agency reports in a story about the program, which has an overall goal of boosting Chinook availability for the orcas 4 to 5 percent.

Washington state has also increased king production, and together both programs have a goal of releasing 20 million smolts annually. Nineteen million were let loose in 2022, 14 million in 2021 and 11.5 million in 2020. There are potential “shirttail” benefits for recreational fishermen.

Other alternatives that NMFS is requesting comment on include just ending the prey increase program, using the money instead for habitat work, or paying fishermen not to harvest Chinook. That last one “could result in similar benefits as hatchery production, but at substantial cost” – an estimated $25 million annually, according to the feds, and would also require further fishery closures.

“The total closure of Chinook salmon harvest in the winter and spring periods was not sufficient to reach a 4-5% increase in prey availability. We determined that in order to reach the desired goals for prey increase, an additional 15% harvest reduction across all U.S. Chinook fisheries during the summer was necessary each year,” NMFS wrote in its analysis.

Release of the DPEIS is the latest chapter in the Wild Fish Conservancy’s lawsuit over NMFS’s 2019 Southeast Alaska biological opinion, which leaned on – at the time – “uncertain mitigation” in the form of increased hatchery production to offset the impacts of commercial fishing off the Panhandle on the availability of Chinook for SRKWs. Uncertainty initially centered around funding, but Congress and the state of Washington came through.

Long story short, a US District Court judge in Seattle ordered NMFS to perform a National Environmental Policy Act analysis on the prey increase program but kept it in place in the meanwhile, as WFC’s demand that it be halted would “lead to increased risk to the health of the SRKW.”

One of the main causes for the decline of Washington’s J, K and L pods is the lack of Chinook, but WFC and its various allies have been trying everything they can to scuttle increased hatchery salmon production for the orcas as habitat work slowly comes on line for wild salmon populations to eventually take advantage of in the decades ahead.

An October 2023 paper from a NMFS contract researcher cast doubts on habitat restoration efforts for Chinook in at least one critical Puget Sound system. Timothy Beechie, et al, found it would be pretty difficult to increase wild spawner abundances on the Stillaguamish River due to “extremely low” marine survival and climate change impacts that are expected to decrease their numbers even more. The Stilly is a pretty compromised basin, but not exceptionally unlike other Puget Sound watersheds.

NMFS’s draft DPEIS also looked at but didn’t analyze several other options – use the $6.2 million for a combination of increased production, habitat work and fishery reductions; target piscivorous birds, fish and marine mammals; produce coho and chums instead of Chinook; etc.

As it stands, the fed’s prey increase program for 2024 calls for rearing and releasing 2 million fall Chinook smolts from WDFW’s Soos Creek-Palmer Ponds complex on the Duwamish-Green, 2 million summer kings from the Tulalip Tribe’s Bernie Gobin Hatchery, 2 million tules from USFWS’s Spring Creek National Fish Hatchery, 1.5 million springers from ODFW’s SAFE facilities on the Lower Columbia, 1 million falls from WDFW’s Issaquah and Wells Hatcheries.

The balance of the 11.75 million spring, summer and fall kings for 2024 would come from Muckleshoot, USFWS, Yakama Nation, Nez Perce and ODFW hatcheries scattered from Lake Washington to Drano Lake to the North Fork Clearwater.

While all of the additional Chinook production is meant to feed the orcas and is modeled to have its largest impact in the so-called salmon highway off the southwest coast of Vancouver Island, it also means more hatchery fish are likely to return to river mouths.

“The fish produced under the prey program are ad-clipped,” confirmed Michael Milstein, an NMFS spokesman in Portland. “Generally, 95-plus-percent (are) ad-clipped, which is more or less standard, as there is always some possibility that a machine goes down or something and some get missed.”

Clipping the adipose fin of the young hatchery fish helps differentiate them from wild salmon.

According to NMFS, 2023 production is modeled to increase Willamette springer returns by nearly 18,000 to SAFE fisheries, Upper Columbia summer kings by 16,540, and mid-Puget Sound fall Chinook by 15,760, among others. Just remember that for anglers to potentially tap into ESA-listed stocks requires available fishery impacts based on wild forecasts.

Public input on the DPEIS is open until Monday, March 11, and comments can be submitted to hatcheries.public.comment@noaa.gov. For more information, see this page.

NMFS is also taking comment on issuing a new incidental take statement for salmon fisheries in Southeast Alaska during the same timeframe.