21 Teams Picked To Help Lethally Remove Olympic Nat’l Park Mtn. Goats In Fall

Twenty-one teams of the “most highly qualified”, WDFW- and NPS-vetted volunteer outdoorsmen have been chosen from a large pool of applicants to help lethally remove mountain goats in Olympic National Park in early fall.

It’s a rare public opportunity for the public to assist in the management of a now-unwanted wildlife species inside what is otherwise an off-limits preserve, and an effort that could be closely watched by anti-hunters and the country at large.

But it will be anything but a trophy or regular hunt, rather an effort to “eradicate” a nonnative species that is heavily impacting natural vegetation.

The National Park Service and Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, along with numerous Westside tribes, have been working since summer 2018 to sharply reduce the numbers of goats – introduced in the 1920s for hunting – inside the park and surrounding national forest lands.

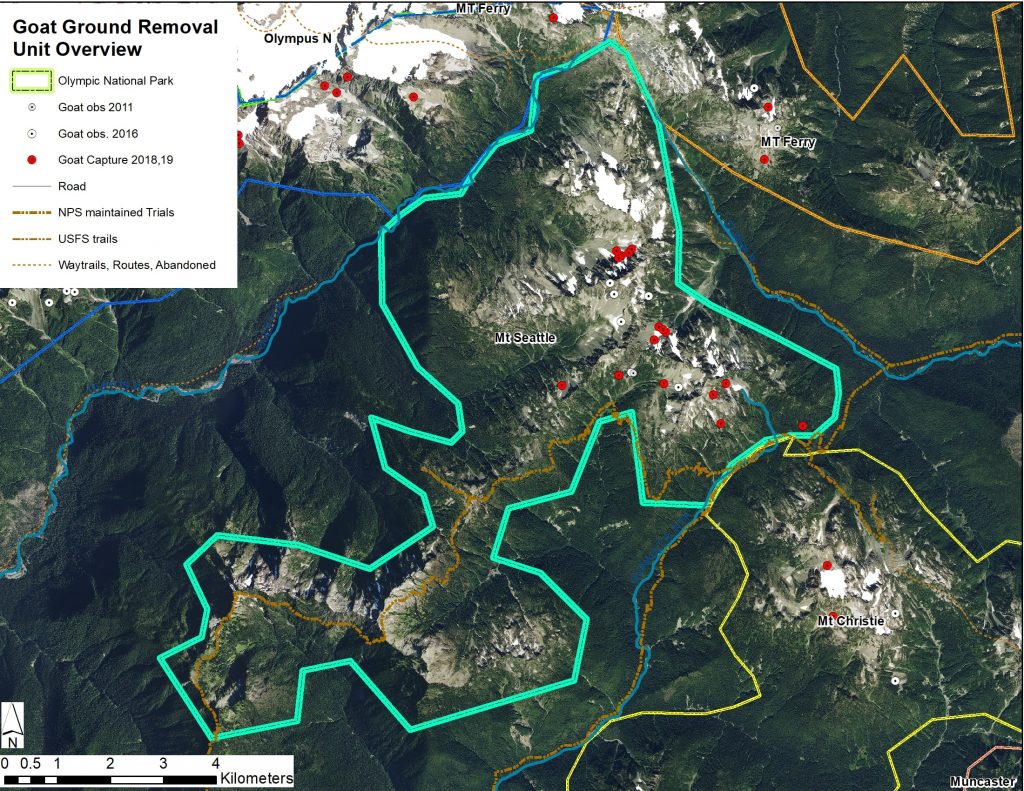

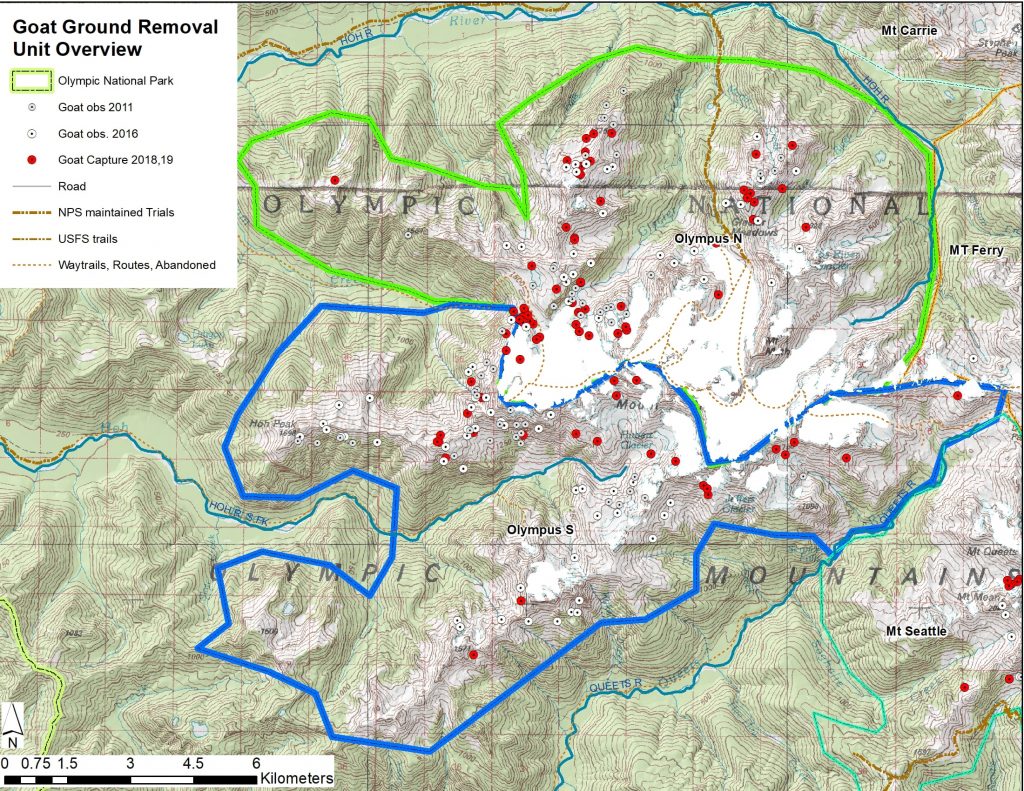

So far 326 have been captured, with 84 percent moved to the Cascades, rebuilding low herds there, and the rest going to zoos, dying during capture or transport, or having to be euthanized for health or other reasons.

There were an estimated 725 goats when the effort began in 2018.

The final round of translocations begins next week, with lethal removals following between Sept. 9 and Oct. 17, it was announced today by WDFW, NPS and the U.S. Forest Service.

Ahead of that, in early April state hunting managers quietly put out word that park officials were recruiting small, three- to six-person groups of “skilled volunteers.”

Given the extremely rugged nature of the interior and eastern Olympics, which are some of North America’s youngest and least eroded mountains, and its weather-lashed nature (Mt. Olympus receives 220 inches of rain a year, including more than 31 in September and October), being physically fit and having a proven ability to operate in the backcountry for long periods were stressed in the application information.

Among the requirements, all team members needed to “Provide a physician’s note certifying physical fitness sufficient to support hiking up to 15 miles a day for 7 consecutive days, carrying a 50 lb. pack, in mountainous terrain.”

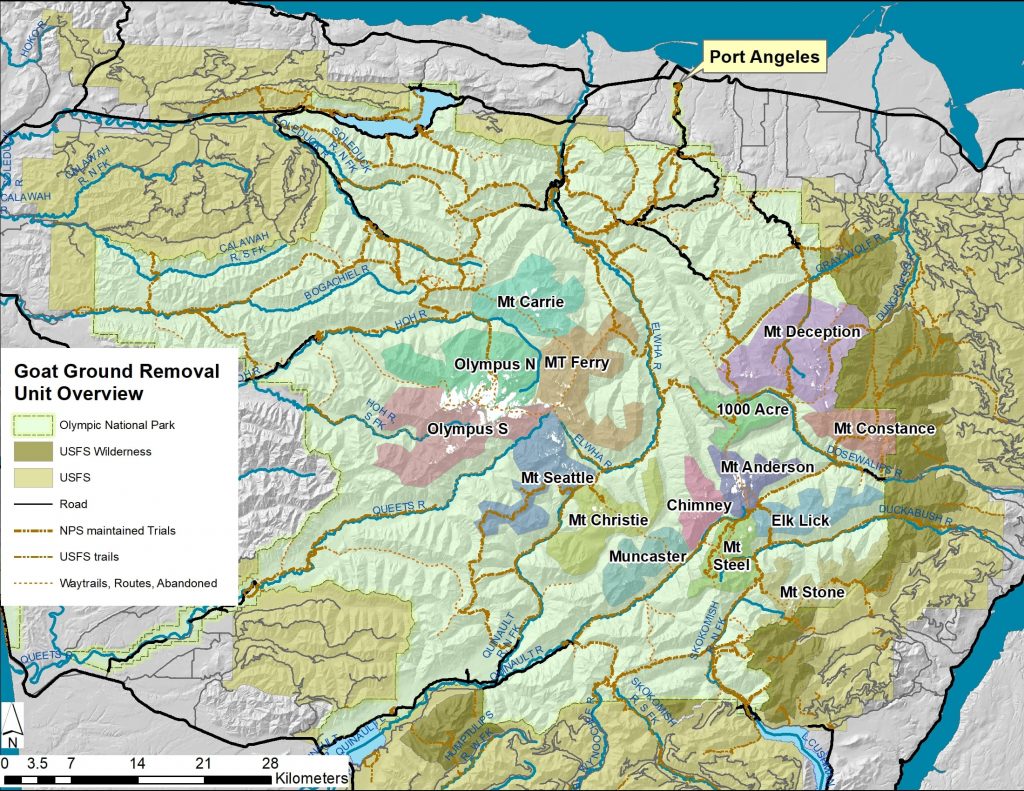

Passing a background check, being available for one of three 11-day-long “removal bouts” in 15 designated areas, and attending a training day were also required.

As unpaid National Park Service volunteers, participants must also abide by federal social media and scientific/scholarly codes of conduct.

Groups could include a mix of marksmen, spotters and packers, but only those who pass a proficiency test – put three out of five shots into an 8-inch circle at 200 yards – right beforehand will be allowed to kill goats.

Only nontoxic bullets can be used – a park document lists more than five pages worth of approved sources, ammo and components for reloaders – and shooters must bring a minimum of 40 rounds.

After collecting biological data on the animals they kill, participants can take the “meat and other materials.”

The application period closed as of April 17.

“We had over 1,200 groups apply,” said Penny Wagner, an ONP spokeswoman in Port Angeles. “We evaluated all applications and pulled out those that were ranked as most highly qualified. From that pool, we then did a random draw of 40 applications and those were evaluated by a team of National Park Service and Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife staff. From that pool, 21 groups were selected.”

She said that “over 100” of the groups were ranked as the most highly qualified.

Patti Happe, the park’s Wildlife Branch chief who headed up the recruitment and selection process, thanked all those who applied, calling the pool “very impressive, and I regret that I can accept so few.”

When it was first announced that mountain goats would be removed from the Olympics, some asked why hunters couldn’t just be tasked with part of the job.

After all, the species is among those that can be pursued by special permit in other parts of Washington, it could be done for free and save taxpayers the high costs of helicopters and ground transportation, and selling tags would raise funds for conservation to boot.

But there has also long been a prohibition on hunting in national parks and changing that would literally require an act of Congress – a tall order in these idiotically overly divisive times.

Ultimately, the project’s final environmental impact statement suggests “using park staff, other federal personnel, hired contractors from Animal & Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) or US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Wildlife Services, state personnel, or trained volunteers.”

The use of select members of the public for lethally removing animals marks an interesting shift in national park management – at least here in the Northwest.

A decade ago, 52 elk were culled at Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado by a small number of volunteers, 868 elk at Theodore Roosevelt National Park in South Dakota, per a 2016 NPS review.

Even so, following WDFW’s call for applications, some sportsmen in a now-21-page-long thread on Hunting Washington expressed concern about the potential for bad public relations fallout.

“Let the Feds pay for their own dirty work, and keep us from getting blamed,” reads one comment.

A member responded, “They are soliciting non-employee volunteers to serve in the same capacity as their hired guns would be; to exterminate the remaining goats. They are asking you to perform the same task in the same way they would hire someone else to do it, so where is the black eye?”

Worried another, sure the park has a “preference” that nannies with kids be taken, which would be more humane than leaving the young goats to just die on their own, but what happens when photos of that get out?

“It will be like the guy that took a picture of the family of baboons he shot,” they posted, a reference to the Idaho Fish and Game Commissioner who resigned after sharing a distasteful image from his African safari.

Olympic National Park has long worried about the “exotic” goats’ impact on alpine vegetation as they search for salt and mineral licks.

The animals, whose ancestors came from the Canadian Rockies and Southeast Alaska, are also attracted to places along trails where hikers pee for the salts that accumulate, as well as campsites where they dump dishwater.

And in 2010 a man was gored and killed by a billy on Klahhane Ridge near Hurricane above Port Angeles, adding impetus to doing something about the population and helping lead to 2018’s translocation and lethal removal plan.

While the park’s social media conduct code includes a stipulation that pictures by volunteer group members of “sensitive topics (e.g., animals …) … shall not be posted to personal social media without approval of the Superintendent, Public Information Officer, or a designee,” participants aren’t barred from talking about the process, ONP’s Wagner says.

In that aforementioned Hunting Washington thread, one member, Chukarhead, indicates their group was among those selected.

“When it came down to winnowing those final 40 groups to 21, we may have had an advantage (just guessing here) because we emphasized our team members’ experience in field science, natural resource management, conflict resolution, and public relations on sensitive topics,” they wrote in early June.

“I’m 100% sure that we weren’t the most experienced hunters or mountaineers, but that’s only one piece of this, and probably not the most important to the managers,” Chukarhead added. “One member will probably do all or nearly all the trigger-pulling with a suppressed precision rifle, and we only have two shooters designated. This is a lethal removal operation, not a hunt, and we put that front and center in our materials. Good luck to others that were drawn. May the clouds be high and the wind always in your face.”

Indeed, good luck on high, this will be an interesting and unique opportunity for outdoorsmen to shine.