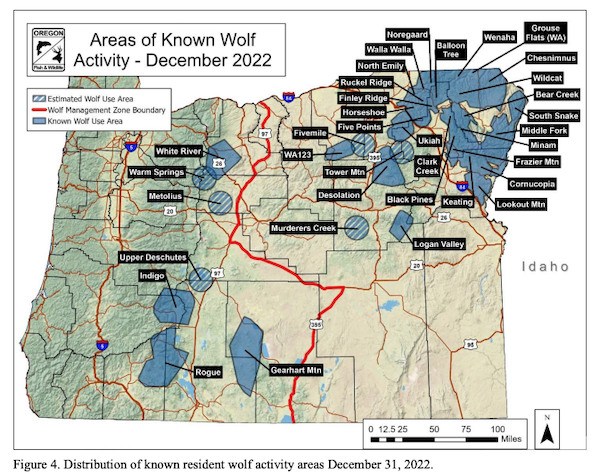

Just as across the big river in Washington, Oregon’s wolf population grew in 2022, tallying a minimum of 178 in 24 packs, 17 breeding pairs and 14 groups, with growth especially notable last year in the state’s West Wolf Management Zone.

That’s a broad swath of the western half of the state where some 22 percent of Oregon’s wolves now occur, up from 13 percent at the end of 2021, and ODFW reports that wolf tracks were even documented in Curry County, on the South Coast, though no animals were counted there during the annual year-end survey.

ODFW identified six packs along with four successful breeding pairs in the West WMZ for the first time – Warm Springs, Upper Deschutes and Rogue in the Cascades, Gearhart Mountain near Summer Lake. The four SBPs is an initial step towards moving to Phase II management if at least four are found at the end of this year and 2024 as well.

Wolf advocates will fret that overall, Oregon wolf numbers only grew slowly – the 2021 count was a minimum of 175 – but after slight declines from 2019 to 2021, pack and breeding pair numbers rebounded and continued their inexorable growth. They howled similarly in 2017 during a period of slow growth, claiming the population was stagnant before numbers rose the following year.

“The population increase in Northeastern Oregon has slowed in some areas as available habitat is filled up and with the turnover of breeding adults in some packs. But wolves are growing in numbers and expanding in distribution in Western Oregon,” said Roblyn Brown, ODFW wolf coordinator, in an agency press release. “We are confident in the continued health of the state’s wolf population as they expand in distribution across the state and continue to show an upward population trend.”

The 2021 figures were 21 packs, 16 packs and eight groups of wolves. ODFW defines packs differently than WDFW. In Oregon, a pack is four or more wolves traveling together in winter, where a group is two or three. In Washington, a pack is two or more wolves.

The state Department of Agriculture awarded $393,682 to 12 counties, three-quarters of which was used for nonlethal preventative measures, the other quarter as payment to producers for confirmed-lost or missing livestock

ODFW reports it investigated 121 suspected depredations statewide last year, confirming 76 – including 27 in the West WMZ, primarily the Rogue Pack – up from 49, a 55 percent rise. The agency says that six wolves were lethally removed in response, while a shepherd legally shot a wolf in the act of attacking his herding dogs.

Those were among the 20 known wolf mortalities, down from 26 the previous year. Nearly all of those occurred in the East WMZ, with two road-killed, seven illegally killed including one by a coyote hunter who turned himself in and paid a $1,453 civil fine for taking a federally listed species, and one dying after getting in a tussle with a cougar, a rare cause of death that somehow is somewhat common in Washington wolves.

Still, the East WMZ “continued to exceed the Wolf Plan minimum management objective of seven breeding pairs and these wolves were managed under Phase III of the Wolf Plan.” ODFW says that four new packs formed there last year – Black Pines, Finley Ridge, Frazier Mountain and Tower Mountain – in areas that had been bereft of wolves, where packs had fallen apart, or between existing groups. Another 13 animals live by themself or in small groups.

As for dispersals, ODFW reports monitoring five radio-collared wolves go on walkabouts, including one to Oregon, one to Washington, one to Idaho, one to California and back, and one within the state.

The agency also states that a survey crew found the collar of a Northeast Oregon wolf in a Southwest Oregon stream.

Where Washington’s growing wolf population continues to be listed under state ESA protections, Oregon’s was delisted by the Fish and Wildlife Commission in 2015, though it remains federally listed in the western two thirds of the state.

More details on Oregon wolves will be presented when the commission is briefed on the annual report at Friday’s meeting in Welches east of Sandy.