Stick A Fork In Them: Battling Bass To Save Coquille Fall Chinook

With invasive smallmouth numbers up and fall Chinook returns deeply underwater, ODFW and a local tribe are going all in to reduce Coquille River bass numbers.

By Andy Walgamott

The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife and Coquille Tribe are putting the prongs in “multipronged effort” as they work to reduce smallmouth numbers on a troubled coastal salmon system.

Not only are spears, spearguns and bait legal again this summer to harvest bass on the mainstem Coquille and its four forks, but electrofishing crews will be expanding their efforts further upstream this year, and planning has begun for a derby to encourage anglers to remove the invasive nonnatives.

Local state fisheries biologist Mike Gray in Charleston says that the bass are a “major factor” in continued low returns of Coquille fall Chinook that are also not bouncing back like on other coastal rivers.

“Other basins (without smallmouth) that took a dip in Chinook returns in 2017 and 2018 have rebounded, but the Coquille remains at extremely low levels. I think what we are seeing is that ‘the Blob’ – persistent warm ocean a few years ago – took the survival on many Oregon coastal populations way down, but the Coquille has not been able to recover to the same extent due to the predation,” he says.

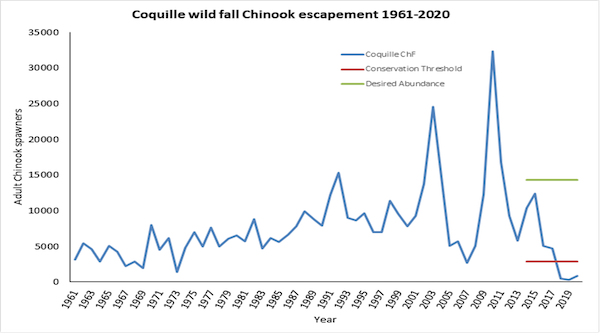

Efforts are also being made to increase Chinook smolt production, but in the here and now, Gray reported last month that this year’s fall Chinook forecast for the system is for “less than 200 fish.” That figure is far, far below the critical run threshold level of 2,500 and because of that, ODFW’s overarching management plan calls for no salmon angling on the Coquille whatsoever this year, wild or hatchery.

It’s a far cry from just a few years ago too. From the mid-1980s through mid-2010s, the basin annually saw an average postfishing escapement of 8,000 wild kings, with bonkers runs in 2003 and 2010 hitting 25,000 and 34,000 fish, respectively.

The highest sport harvest of the past 25 years was 6,625 Chinook from the bay, mainstem and forks in 2015 – a great year for many coastal systems – and the average from 1996 to 2018 is 2,656 fish. Both figures make 2022’s expected sub-200 escapement stand out all the more and demands something be done about it right now.

GRAY ACKNOWLEDGES OTHER factors are in play and biologists are also seeing confounding signals this year with dips in Siuslaw and Tillamook fall runs. But he says evidence that bass are having a big impact comes from stomach content sampling that shows smallies feed on juvenile Chinook, as well as lamprey, another native species.

What’s more, there are now tons of bronzebacks in the system.

“The numbers and density of bass – particularly young-of-the-year and age 1 – was amazing from last year’s blitz,” Gray states.

That’s a reference to the “Smallmouth Blitz” conducted last August on the Coquille by 30 ODFW biologists who were joined by Coquille Indian Tribe staffers and Trout Unlimited volunteers. The weeklong effort was conducted “to assess the smallmouth bass population to determine whether or not removal can be successful at reducing this limiting factor for native fish, and what level of removal would be necessary,” Gray says.

Bass are particularly concentrated in what he termed the “confluence zone,” that stretch of water where the South, East, Middle and North Forks of the Coquille come together near the town of Myrtle Point. Above there are the salmon spawning grounds, and that forces Chinook smolts headed to the ocean to pass through a “gauntlet” of bass.

Striped bass also occur up to this zone, and they’ve been here much longer than smallmouth.

Chinook exhibit a range of early life histories, with some rearing longer in freshwater than others. The Coquille’s are a zero-age outmigrator, which means they’re “so much smaller/younger … than coho or steelhead that migrate as age-1-plus or older smolts,” says Gray.

He speculates that that could make them more vulnerable to predation by bass, which they would be meeting for the first time on their spring swim downstream.

Data from the Smallmouth Blitz is being fed into modeling and when it’s ready, it will be used to figure out how to effectively control bass predation, Gray says.

“We could (hypothetically) be pulling 5,000 smallmouth out each year and having little to no effect on predation, but we need to be informed as to what is possible,” he says.

MEANWHILE, ROUND TWO of electrofishing work is slated to begin this month. Chinook smolts from the upper watershed will have migrated out of the river by then. ODFW and the tribe also have to avoid the times of year when they might encounter coho, either smolts or returning adults, which are listed under the Endangered Species Act. The work required sign-off from the National Marine Fisheries Service.

Last summer’s electroshocking, done with a single boat lower in the system, removed north of 5,000 bass, but this year’s expanded plans call for zapping the river from tidewater well upstream to areas where crews will need a raft or pontoon to access.

It’s unclear where bucket biologists illegally transported the Midwestern natives from – probably the Umpqua, which is just 60 to 80 road miles away and was unlawfully stocked with smallmouth in the 1970s – or when and where they were first placed. A 2005 report notes unconfirmed angler catches in the Middle Fork Coquille and Fat Elk Slough. Nevertheless, in 2011 the species was confirmed in the South Fork. ODFW believes at that point “the fish had been in the river for multiple spawning cycles.”

“It has been primarily in the last five to six years that our sampling has shown them fully distributed to most of the suitable habitat in the basin, and in numbers that pretty much seem to fill their niche. This seems to coincide with the onset of the warm ocean conditions,” Gray states.

Besides the blob, recent years’ river conditions that have been inhospitable for salmon have been great for bass.

Droughtlike conditions in spring reduce habitat and cover in the Coquille at what should be a higher-flow time of year, leaving smolts with less room to evade predators, while summer temperatures have made it too warm and then in fall, low flows concentrate Chinook redds in areas of the channel that are then subject to scouring floods as atmospheric rivers crash into the region.

“For the Coquille, particularly in recent years, river flows are dropping and temperatures are warming during the salmonid smolt outmigration,” Gray says. “This year seems to be a wetter spring than we have been having recently, except that February-March we saw ‘summer-like’ low flows in local basins. Things went back to being pretty wet in April-May, so hopefully that bodes well for outmigration this year.”

WHEN I POSTED the news last month that ODFW was for the third straight summer allowing spears and bait on the Coquille, some online questioned how bass, salmon and steelhead seem to be able to coexist in Oregon’s Umpqua and John Day, as well as the shared Snake, but Gray points out those are very different systems.

They are all “much larger than the Coquille, and have snowpack or water releases to hold down temperatures and hold up flows in the spring. The Coquille is a Coast Range basin, and relatively small compared to the ones mentioned. Its flows are not held up by snowpack as the spring develops,” he says.

That’s a key for smolt outmigration.

“I worked in the John Day District for nine years, and we monitored smallmouth/salmonid interactions while I was there. Since I left there in 1999, there has been a research group working in the John Day doing more intensive research on the salmonid populations, including predation from nonnative fish. One factor we found in the John Day was that for juvenile salmonids to make it from upper basin rearing grounds through the main river to the Columbia River, they were passing on elevated flows and low river temperatures from spring snowmelt. This was a time when predation rates were low,” Gray says.

Another comment online was that ODFW’s efforts are actually all about ensuring federal funding keeps flowing to the agency more so than they are to recover Coquille fall Chinook.

“There is no validity to that,” responded Gray. “This is about taking proactive steps.”

THE COQUILLE’S SALMON are not only important to coastal anglers, who harvested 61,089 fall kings out of the system from 1996 through 2018, per ODFW records, but the Coquille Tribe.

“Coquille River salmon have nourished my people for countless generations. Our ancestors have relished and revered these amazing fish since time began,” states chairwoman Brenda Meade on the tribe’s website, coquilletribe.org.

(While the river is pronounced “ko-keel,” the tribe is known as “ko-kwel.)

But with the big population crash, the tribe fears fall Chinook are now “on the edge of extinction” and last August the tribal council declared an emergency.

The Coquilles too point to smallmouth bass as a key factor, but also broodstock collection shortfalls due to low runs, pinniped predation on returning adults, plus environmental factors, “old deteriorated fish hatcheries” that “produce too few smolts,” “rigid state policies” that “prevent effective management” and a river that is a “low priority in the state budget.”

That may be changing as last month the Oregon Fish and Wildlife Commission unanimously approved an amended memorandum of understanding with the tribe that, in part, allows for cooperative natural resource management in five Southwest Oregon counties and nearshore waters. It also allows for ceremonial and subsistence harvest – but not commercial take – under tribal regulations and enforcement in partnership with ODFW and state fish and wildlife troopers.

Last summer Meade told KLCC, a public radio station based in Eugene, that smallmouth removal would be an “an ongoing effort for decades to come.”

“If we can take some of the invasive species outta there to give those salmon a fighting chance, that will be a success, but it’s quite possible that we can never completely eradicate them,” she acknowledged.

It’s a truth that fishery managers across the Northwest face as they work to suppress nonnatives – walleye in Lake Pend Oreille, northern pike in Lake Roosevelt, brook trout in Northeast Oregon alpine waters – to benefit native or more desired species. But this spring’s discovery of walleye in three different Southwest Idaho waters also highlights the mountain in front of them – the persistent actions of bad actors who want to have the fish they prefer wherever they want them, and to hell with the biological ramifications, let alone the expense of dealing with cleanup.

Besides controlling the bass, ODFW and the tribe are taking other proactive measures to help the Coquille’s salmon run.

“We are trying to take actions to reduce the impact of some of those factors, at least the ones we have some control over – release larger/older smolts in early spring flows; continue working on habitat restoration actions that improve in-river conditions,” Gray says.

He describes working with the tribe on a conservation hatchery program to collect wild Chinook to spawn and raise and release 50,000 larger smolts each spring.

“These releases would be from the upper basin where spawning occurs, but the objective would be to release at a time when they would be flushed from the system on cooler/higher flows, when smallmouth metabolism is low,” Gray says.

Because these particular smolts are meant to rebuild the wild run, they won’t have their adipose fin clipped and thus won’t be available for harvest, but he says they will be internally tagged so that the effort can be monitored.

Last fall also saw ODFW and the tribe collect broodstock for the river’s hatchery harvest program, but due to the low return and despite “great effort,” only 50 to 60 percent of the eggtake goal was reached.

Some of those young salmon will be used in this new release strategy.

“We are looking to take a portion of those juveniles and do a spring yearling release in 2024. The CIT recently acquired property on Lampa Creek in the lower Coquille basin, and we are working with CIT to conduct a ‘pilot’ acclimation/release of 1,000 of those juveniles in the next few weeks. An additional 1,000 of the 2021 brood will be held to a spring yearling for acclimation/release in 2023. These fish and the remainder of the 2021 brood currently in our hatchery system are (adipose)-marked for future harvest opportunity,” Gray says.

BACK TO SPEARFISHING. In the Northwest, the sport has primarily been practiced by anglers swimming in pursuit of bottomfish, either along the Oregon Coast or in Puget Sound and the Strait of Juan de Fuca, so there’s a bit of a learning curve around the authorized gear. To that end, ODFW posted four videos on its YouTube channel (youtube.com/user/ieodfw) describing the Coquille bass issue, basic info about the equipment, how-tos, safety concerns, filleting tips and, in the latest installment, how to build your own spear gun.

“They really seem to like the rocky structure,” notes Stuart Love, a spearfisherman and local ODFW wildlife biologist, in the first video. “Generally the fish are in fairly shallow water, even in the deeper holes. They don’t seem to be down in the very bottoms. We find most of the fish in about 5 feet of water.”

Bait will likely be the more effective and most used tactic on these fish, but Oregon fishery managers are also sending a strong signal by lifting the prohibition against using spears here. They’re otherwise banned in all freshwaters for all game fish. A fishing license is required and spears and bait are allowed through October 31.

Another rare step that illustrates how serious ODFW is about the problem is that the agency posted maps of smallmouth distribution in the Coquille system, plus access points on the mainstem and the South Fork. Hot-spotting like that has almost become taboo in this social media age.

And finally, the agency is also mulling incentivizing the removal of the bass.

“We are working with volunteers to develop a ‘derby-type’ event to allow anglers to assist with removal of smallmouth over a weekend or derby period,” says Gray. It will need to comply with ODFW’s bass tournament rules, he says, but stay tuned for updates.

No doubt that smallmouth are one of the top sport fish in the country, a species known for eager bites and great fights. They absolutely have a spot in the grand pantheon of North American game fish. But in Oregon on the Coquille system, managers want you to stick a fork in them. NS