Sheriff Says Wolves In Klickitat County A ‘Bad Idea’

With a breeding pair of wolves already in the area, a Southcentral Washington sheriff says the species shouldn’t be “introduced” in his jurisdiction and that arresting someone for shooting one to protect their livestock or pets would be a violation of their constitutional rights.

“The introduction of wolves into Klickitat County is a bad idea in my opinion. Wolves will be killing livestock, domestic pets, and will present a public safety threat to our citizens,” stated Sheriff Bob Songer in a press release late last week.

Songer said that it’s his understanding that wolves “are already being introduced into Klickitat County” and “are to be Federally protected under the Endangered Species Act” and state law and that means they can’t be killed if they’re attacking or killing livestock or pets, which he disagrees with.

“As a Constitutional Sheriff of Klickitat County, it is my duty to protect our citizens Constitutional Rights and God Given Liberties,” he wrote. “I believe the Federal and Washington State Governments, threatening to arrest a citizen for killing a wolf that is attacking or killing livestock and domestic pets, which is the personal property of our citizens, is illegal and unconstitutional.”

Constitutional sheriffs believe their authority trumps state and federal law.

Songer’s statements on wolves represent another potential clash over predator management with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. His 2019 Dangerous Wildlife Policy declared that deputies and a voluntary posse would be the primary responders to cougar and black bear when it comes to public safety issues. And his words will further a long-running semantic battle over how we say how wolves got here.

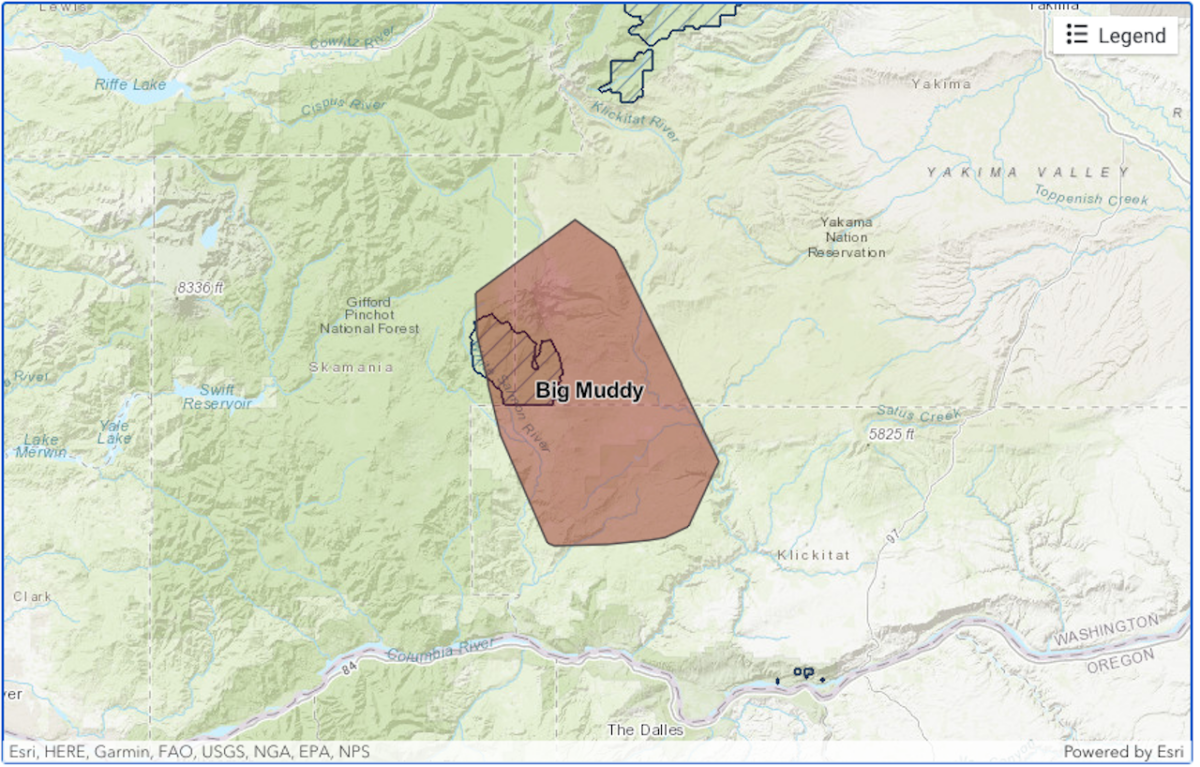

Asked if WDFW had any comments or a response to the sheriff, spokeswoman Staci Lehman in Spokane stated that the “naturally reestablished” Klickitat wolves – known as the Big Muddy Pack and which roam into southwest Yakima and eastern Skamania Counties as well – came from source populations elsewhere in Eastern Washington, which themselves originated “without any reintroductions” from packs in Canada and the Northern Rockies.

Wolves were also reintroduced by the federal government in Central Idaho and Yellowstone in the mid-1990s. They were removed from ESA protections in 2011 there and in the eastern thirds of Washington and Oregon, but today are listed elsewhere in the greater region, and they remain protected under state law as well in Washington.

“All of Klickitat County is within the western two-thirds of Washington (west of Highways 97, 17 and 395), where wolves remain under federal protection as endangered and it is illegal to lethally remove, haze, or otherwise harass a wolf, even if the wolf is involved in the act of depredation of livestock, pets, or property loss,” Lehman added.

In 2013, at the request of state lawmakers, the state Fish and Wildlife Commission voted unanimously to allow owners of domestic animals – ranchers and pet owners alike – to kill a wolf seen attacking their animal or animals in areas where wolves are federally delisted, a rule permanently enshrined in the Washington Administrative Codes as WAC 220-440-080. Prior to that, only commercial livestock operators were allowed to shoot a wolf, and only after they had been issued a permit by WDFW.

There have been at least eight such caught-in-the-act incidents since then, mostly involving cattle being chased by a wolf or wolves, but at least one was shot in the Blue Mountains to protect a cabin owner’s dogs. By and large, they’ve occurred where wolf numbers are greatest.

The commission rule was essentially extended across Washington in early 2021 when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service officially declared wolves recovered in the western two-thirds of the state and elsewhere. However, that was negated in February 2022 when a U.S. District Court judge in California ruled against the delisting and put the species back under ESA protections outside the Northern Rockies.

Just a week and a half ago, in a 6-3 vote the commission denied a petition that in part requested caught-in-the-act provisions be tightened in the eastern third of the state to only allow livestock owners to shoot a wolf attacking their animal(s), and only if a depredation has already occurred in the area and only if the owner had a permit from WDFW. The citizen panel is also slated to vote in early 2024 on the agency’s proposal to downlist wolves across Washington from endangered to sensitive following strong average annual growth of 23 percent since confirmation of the first pack in 2008.

Despite expectations that wolves would readily colonize the South Cascades, with its vast national forest and large elk herds, it has taken awhile for any to set up shop here. In 2014, a wolf was photographed in Klickitat County, but it wasn’t until January 2022 that another was confirmed in the area. That GPS-collared male had dispersed from a pack territory south of Wenatchee earlier that winter and it was joined in early spring by an uncollared female. Together they were named the Big Muddy Pack by the Yakama Nation and according to a tribal flyer, were a breeding pair this year.

The pair represents the first pack in WDFW’s South Cascades and Northwest Coast recovery region, making them important towards reaching state goals, as well as officially served notice that what ranchers elsewhere in the state have gone through had arrived in Klickitat County.

“WDFW staff work closely with landowners to help deter potential livestock/wolf interactions using non-lethal deterrent methods. In addition, presentations and workshops for landowners have been held in Klickitat County to discuss living with wolves on the landscape,” agency spokeswoman Lehman stated.

As for Sheriff Songer’s public safety concerns, a decade and a half into wolf recovery in Washington, there have been a few unnerving encounters between wolves and humans. Those include a Stevens County elk hunter who described being surrounded by a pack near Smackout Pass and shot at one in self-defense in November 2014 and a Forest Service stream surveyor who had to climb a tree twice after stumbling upon a Loup Loup Pack rendezvous site in Okanogan County in July 2018.

The greater danger with wolves is bringing a domestic dog near a den or other wolf gathering area.

“Wolves have a strong aversion to humans and will avoid them,” reads that Yakama Nation flyer, which was posted in late June. “During the recreation area open period, there is a chance that people may see or hear the wolves, but more likely, the wolves will avoid the area and human interaction.”

They are wild animals.