New Joint-agency Work Group Formed Around Walleye, Nonnatives In Snake, Columbia

Another clear warning about walleye expansion up the Snake has been issued by Idaho salmon and steelhead managers, who also unveiled a new focus on addressing nonnative species in that river and the Columbia.

Not only are far more walleye moving past Lower Granite Dam than previously believed, but they’re overlapping more and more Endangered Species Act-listed fall Chinook and summer steelhead rearing habitat and have been caught at the mouths of the Clearwater, Grande Ronde and other rivers, out of which swim many wild and hatchery smolts.

And stomach sampling last year found salmonids make up a larger part of walleye diet than native northern pikeminnow, which are being actively suppressed for just that reason, as well as introduced smallmouth bass in almost all cases in the four lower Snake River reservoirs.

While there are still many questions around Snake River walleye out there – are they moving upstream to feed or have they now established a breeding population above Lower Granite, and if so, where do they spawn and how many are there? Did bucket biologists give this popular Midwest fish a helping hand? – a new state-tribal-federal work group has also now been formed to address the species and several others in the Columbia Basin.

That’s the nut of a presentation earlier this month to the Northwest Power and Conservation Council by Marika Dobos, a fisheries biologist with the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, and first reported by NewsData’s Clearing Up news service and the Columbia Basin Bulletin.

It follows on the increasingly alarming updates in recent years from IDFG and echoes what I’ve been reporting the past two years about growing incidental catches of walleye turned in at Lower Granite by Northern Pikeminnow Sport-Reward Fishery participants – 2,085 last year, which was nearly twice as many as 2022, which itself was 12 times 2021’s tally.

And it all should signal that there appears to be an increasing urgency around the issue given the ongoing struggles of salmon and steelhead and the billions of dollars that have been spent on recovering them, and the new renewed focus toward that end, including possibly breaching the lower Snake dams, by the “six sovereigns” and the Biden Administration, many of which are on that new intergovernmental panel.

Dobos said the Walleye/Non-Native Piscivore Work Group is made up of representatives from IDFG and the Washington and Oregon Departments of Fish and Wildlife, the Umatilla and Nez Perce Tribes, the U.S. Geological Survey and the National Marine Fisheries Service’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center, and it has already adopted a mission statement: “Implement research and management actions with a goal to reduce, minimize, and prevent piscine predation-related mortality from introduced non-native fishes on anadromous species within the Columbia River basin.”

SO HOW DID WE GET HERE? Since walleye were illicitly released into Banks Lake perhaps as far back as the 1940s, they have inexorably spread down the Columbia, but it wasn’t until the late 1990s that they apparently first swam up into the Snake.

Dobos told members of the Northwest Power and Conservation Council, which balances hydropower generation in the Columbia Basin with mitigating its impacts on fish and wildlife, that red flags about potential impacts to Idaho’s young salmon and steelhead really began to go up in 2016 when the first two walleye were observed at the fish trap at Lower Granite Dam, the fourth barrier on the Snake above the Columbia. Trap numbers have risen nearly every year since, and 2023’s 154 was more than twice as many as both 2021 and 2022, 75 and 73, respectively.

She said that the walleye being seen have already grown to a size where their diet has switched over to fish, and their arrival in the trap in recent years has also moved earlier, from mid-August in 2020 and 2021, to July 1 in 2022 and early June in 2023, which also puts them more in the window of smolt outmigration.

But the trap count only reflects a percentage of passage – and much less than previously known. It had been assumed that 20 percent of all species were caught in the dam’s trap, a sampling facility not meant to capture all fish passing by, but the situation with walleye showed that’s not necessarily the case.

Dobos explained that while the Army Corps of Engineers isn’t contracted to count walleye and other “nontarget species” at the dam, they did agree to provide window counts for April-October 2021.

“And they counted nearly 2,000 walleye,” she said. “And what’s alarming is that we only caught 3 percent of those in the trap, and so that disparity was not something we expected. Because the trap rate runs on average 20 percent, we were expecting that 75 was 20 percent of the walleye in the ladder, and that’s not the case.”

That led to a test with last year’s 154 trapped walleye. Instead of being killed like those that turned up in the trap in 2020, 2021 and 2022, these were given passive integrated transponders, or PIT tags, and released back below Lower Granite to see how they moved through the dam, which is well equipped with sonar arrays to read the signals of passing tagged fish – except through the barging locks. Almost half the walleye entered the ladder again, Dobos reported.

The data did suggest some ways to somewhat mitigate passage, if managers could agree on approaches, she stated.

In response to her presentation, Ed Schriever, an NWPCC member representing Idaho, favored a “hit ’em hard and hit ’em fast and don’t take your foot off the gas” approach applied where there would be less collateral damage from gillnetting, electroshocking or poisoning to the native species that managers are trying to save. He said the first priority is to determine if walleye are already spawning above Lower Granite.

“If we’re just recruiting new animals through the lock or the ladder, it seems like the most urgent thing we can look at is, how do you make changes to the ladder? Walleye aren’t the strongest swimmers in the world. Can we sort them out by making it harder to get through the ladder and still allow those fish we want to get through the ladder, get through the ladder?” Schriever asked.

He also acknowledged it may be too late for that, but advised Dobos to figure out how to stop the flood.

“I’m looking at your counts; they’re ready to go ballistic, and they may already be. It’s quite possible there’s enough fish that have expanded their range; if they are successfully reproducing, that horse has left the barn. I hope that’s not the case, but I would really encourage you to be thinking about significantly slowing down the rate in which these fish are crossing Lower Granite,” Schriever urged.

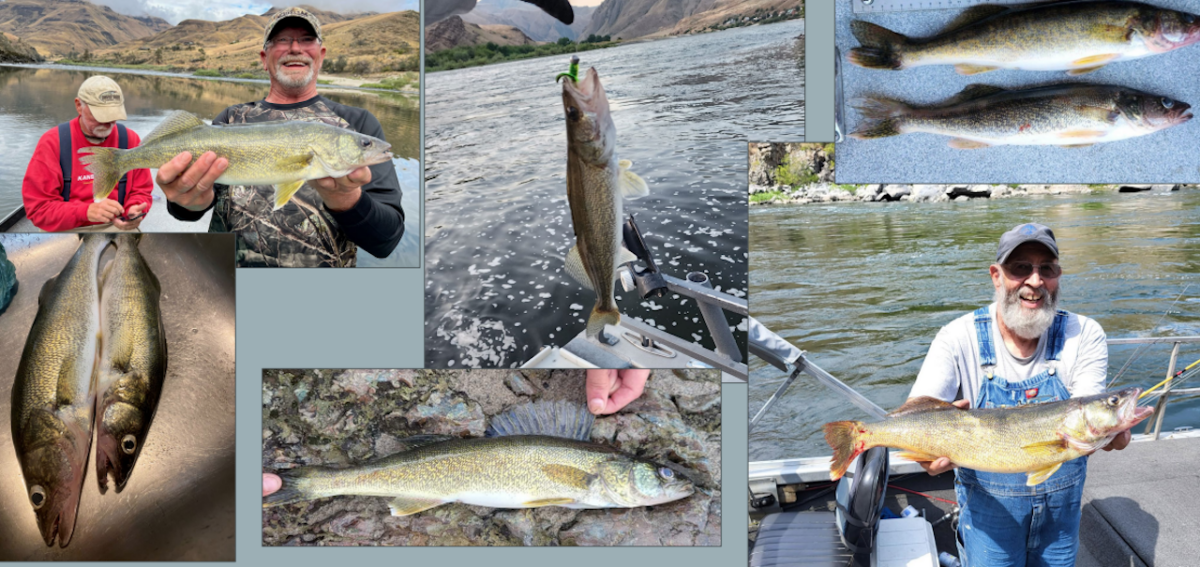

IT’S NOT JUST TRAP DATA RAISING EYEBROWS, but angler catches reported to IDFG. The agency has been putting out the word in recent years asking fishermen to report their Snake system landings to the nearest regional office, and in 2023 they heard about 16 different walleye – four times as many as all previous years combined.

“This was a big number and it was pretty concerning. What was even more concerning was where these fish were caught,” Dobos said.

A map she shared showed catches at the mouths of the Clearwater River, Asotin Creek, the Grande Ronde, the Salmon and both further up the Salmon as far as Riggins and well up the Snake into Hells Canyon.

Additionally, in that Clearing Up story, WDFW Region 1 Fish Program Manager Chris Donley said walleye are beginning to be seen in fish traps on the Tucannon River, below Lower Granite, and he speculated they might also be above there inside the Ronde and Oregon’s Imnaha.

Walleye have been off the mouth of the Tucannon much longer than those two other Blue Mountains tributaries, but it is emblematic of where the danger really is for fish that did not evolve with and learn to fear walleye.

“We’re starting to get much more overlap in these juveniles that are trying to make it out to the ocean, so they’re spending some time in these large rivers (with walleye) until they make it out to the ocean,” IDFG’s Dobos said. “It’s also overlapping some of our hatchery releases for these very important mitigation programs.”

She specifically pointed to Idaho fall Chinook, which are lower mainstem spawners.

“The juveniles are actually rearing a lot longer in some of these lower rivers,” Dobos said.

The triumphant rebuilding of that ESA-listed stock, led by the Nez Perce Tribe, allowed for the resumption of tribal and state fisheries in 2009 after a 35-year cessation. Harvest rates up and down the Snake and Columbia are constrained by the Snake River wild, or SRW, component of the overall run, but WDFW catch stats for 2021, the most recent year available, show 1,178 clipped and unclipped adult fall kings were retained that season.

“Fall Chinook nearly blinked into extinction in the Snake River, and a lot of folks have worked really hard to build that program up over the years, and have done a really good job, and it’s one of our few success stories in the Clearwater,” Dobos stated. “And if walleye continue to colonize and establish in more numbers in these reaches, that could spell a different story for this program in a very short amount of time.”

WDFW’s Donley told Clearing Up that when walleye begin spawning in the same tributaries as salmon and steelhead do, the impact “goes through the roof.”

Dobos’s presentation touched on how that occurs.

“We have steelhead in the Clearwater that will occupy the mainstem Clearwater and Selway and Lochsa River for multiple years before they go out to the ocean. So what’s happening is, you’re expanding the amount of time that these fish are overlapping with these predator fish and there’s a higher risk that walleye are just going to capitalize on this food source in the future. So it’s really concerning,” she said.

And as walleye establish themselves in lower portions of Snake tribs, pilot fish will continue to expand the population into the higher rearing areas for the basin’s spring-summer Chinook and summer steelhead, Dobos warned.

DOBOS ALSO SHARED 2023 ELECTROFISHING data from ODFW, part of an every-three-years effort to track relative abundance of northern pikeminnow, smallmouth bass and walleye and their diets in the Snake. Last year, crews shocked up walleye for the first time in the Lower Granite Pool, finding them above Clarkston, she said, and they also saw a “significant” spike in relative walleye numbers in the Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental and Little Goose tailraces.

ODFW pumped the stomachs of fish they’d electroshocked, she also reported.

“Salmon and steelhead … made up a large portion of walleye diet. That’s not surprising; what’s surprising is that when you compare it to northern pikeminnow and smallmouth bass, walleye had the highest proportion in most cases,” Dobos said.

It will have been a point-in-time estimate and likely collected when you would expect smolts to be available in some numbers and on the move downstream, but salmonids represented 50 percent of walleye diet at Lower Granite, 47 percent at Ice Harbor, 30 percent at Little Goose and 14 percent at Lower Monumental, according to the data Dobos shared.

Little Goose was the only place where either of the other two species outconsumed walleye, and just barely – salmonids made up 33 percent of the northern pikeminnow diet there.

More information on ODFW’s electrofishing efforts should be spelled out in the forthcoming 2023 annual pikeminnow program report, but Dobos also compared and contrasted past and more recent salmonid consumption rates. In the early 1990s, early on in walleye colonization of the Lower Columbia and at a time of relatively suppressed salmon populations, they ate less than half a smolt a day at peak outmigration, she said. In the McNary Pool in May and June 2016, a time of more robust mitigation programs, an established walleye population consumed 2.52 young salmonids a day.

“So you have higher consumption and you have a lot more mouths to feed. And I can tell that you most of these are from fall Chinook consumption from the upper Columbia bright program,” Dobos said. “If the prey are available, these fish capitalize on it and they do a pretty good job of adapting to the situation.”

INDEED, WALLEYE ARE JUST DOING WHAT WALLEYE do. They’re not bad fish, IDFG has stated in the past. Given access to new waters with naïve and abundant feed, of course they’re naturally going to colonize them. It’s a story as old as mankind and the Earth itself.

But the size of both the Snake and Columbia Rivers, the multitude of managers involved and the strong year-round overlap between anadromous species and walleye makes managing them a “logistical nightmare” at this point, Dobos acknowledged to the council. Even in waters not connected to the sea, walleye suppression efforts “have been met with a lot of difficulties,” she added.

She said that one of the biggest challenges managers face – and one not often talked about – is the angler support seen for walleye in the Inland Northwest.

Both the delicious eater-sized fish and the “big girls” – those egg-stuffed trophies that just might get your name in state record books this time of year – are revered by some. And with a lower stigma around keeping them than with bass, Stizostedion vitreum represents a “bridge” fishery between fall and spring salmon runs, among other times of the year, helping to put filets in fishermen’s frying pans and greenbacks in guides’ wallets.

“There’s a community out there that is very supportive of having walleye everywhere,” Dobos said. “These folks are very boisterous, they’re a very strong group, and if pushed to the suggestion of managing walleye, they do get organized and they will be something to – a difficulty to try and mitigate through,” she said.

Sheila Hasselstrom can tell you that better than many. She’s the president of the Clearwater-Lewis County chapter of the Idaho Farm Bureau and she and her husband Eric raise cattle and sheep on 3,000 acres on the Nez Perce Reservation just north of Winchester.

When they can break away from the farm, the Hasselstroms enjoy taking trips to catch walleye, as well as bass and steelhead. It was while talking with guides about growing numbers of walleye at the Snake-Clearwater River confluence that an idea was born in Sheila’s head.

“(Walleye) are predator fish that are eating our salmon, and they are migrating right upstream to our salmon hatcheries. The truth of the matter is that a high percentage of salmon smolts are being eaten by predators like walleye and birds on their journey to the ocean and a high percentage of adult salmon are being eaten by non-native sea lions and seals on their trek back up the Columbia to spawn, but not much at all is being done about that,” Hasselstrom told me.

After pitching her county board on hosting what became the “Farmers for Salmon: Walleye Jackpot” out of Lyons Ferry on the Snake, Hasselstrom said they contacted the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife to go over the nuts and bolts. She recalled she was advised to call it a jackpot and not offer payouts like a traditional competition. Fish are largely released alive at walleye and bass tournaments, but this was to be a catch-and-kill event with prizes awarded via a ticket drawing.

“As farmers, we care about salmon recovery, and we just want to draw attention to the predator problems in the river system,” Hasselstrom told me. “This event was to be a fun way to engage the agricultural community in a sideline problem to salmon recovery.”

Soon, the statewide Farm Bureau board offered money to help with funding, she said, and it took off from there, with guides contacted to hold boats open and IDFG asking to tag along and collect biological samples as part of their research into Snake River walleye movement.

However, as word about the Walleye Jackpot spread further, Hasselstrom faced “extreme pushback,” and so she decided to cancel.

It all left her puzzled.

“We understand that sportsmen and guides are protecting their walleye and bass populations to preserve their businesses,” Hasselstrom said, “but walleye and bass are both nonnative species that feed on salmon and steelhead smolts as they flush to the ocean. Washington Fish and Wildlife currently have no limits on walleye, but what we have seen is that the guides are throwing back the big trophy mommas and limiting their customers to 12 to 15 fish per day.”

“This begs the question,” she asked, “have sportsmen and guides given up on salmon and steelhead?”

IT’S A TOUGH QUESTION. I KNOW I haven’t whatsoever, which is why I’ve spent so much damn time reporting on this growing danger of building walleye numbers in the Snake (along with shad, northern pike and walleye in Lake Washington, pike everywhere, smallmouth bass in the Coquille, etc.).

But I can also see how Chinook and summer steelhead might not be for all anglers, especially those who’ve come here from Minnesota, Wisconsin or elsewhere in the native range of walleye. Given the widespread belief in conserving the resource in anglerdom, I can understand why some limit their take and release the spawners so as to perpetuate the species ad infinitum.

And lord knows that decades of doom-and-gloom stories about salmon and steelhead runs with few bright spots will have folks trying to dial in a fishery that looks to have legs and ain’t ever gonna be kiboshed by poor ocean conditions, or commercial fishing on the North Pacific or mid-Columbia, or pinniped predation, or managers’ allocations, or ESA restrictions, or all of the myriad other things impacting salmonid returns and making for less stable fisheries. I mean, when the hell was the last time you ever saw walleye season closed by an emergency rule change notice!?!

A couple months ago when I brought the Walleye Jackpot up to a longtime salmon fishing world source I very deeply respect, I was gobsmacked to essentially hear a meh out of them. But their argument was that removing invasive fish hasn’t been shown to be effective in bringing back native ones, so why upset walleye anglers’ apple cart?

Furthermore, biologically, the growing walleye population is emblematic of the Snake’s altered state, they asserted. Nonnatives and even native ones like northern pikeminnows are just going to do a lot better in modified habitats than Chinook, steelhead and coho.

A better plan, they argued, was to restore what salmonids need, including focusing on reducing water temperatures through streamside habitat improvements and buffers. Cooler flows might help offset the advantage walleye will receive as climate change continues to warm rivers.

Sheila Hasselstrom and I will find ourselves on very different sides of breaching the lower Snake dams –they’re critical to her region for transporting wheat and other products to market; removing them is likely to sharply improve spring Chinook smolt survival and potentially reclaim lost fall Chinook spawning grounds for me – but I do very much applaud her for the Natural Resources Conservation Service programs she says she and her husband have implemented on their farm.

“They range from changing our tillage program to a no-till practice (to reduce tillage erosion) to fencing off our streams from livestock access, and implementing riparian waterway planting to absorb nutrient loss from our farm ground,” she told me.

Hasselstrom added that her county’s forestry and agricultural communities also look to how best they can protect streams and reduce erosion and runoff.

“This protection improves water quality and salmon populations. In Clearwater County, the Clearwater River brings a large amount of revenue in the form of tourism to the town of Orofino with salmon and steelhead fishing,” she stated.

While the Walleye Jackpot was canceled, she, fellow farmers and a few guests fished out of Lyons Ferry on March 20th anyway and kept a reported 69. It was a trip I was invited on but couldn’t make because of my April deadline.

IF HASSELSTROM SHIED AWAY FROM BACKLASH over killing walleye in the end, not so one of her veritable neighbors. In a pair of recent articles, Eric Barker, outdoor reporter for the Lewiston Tribune, advised anglers to do their part and eat more of ’em and said he was going to give it a go himself, publishing fishing tips from a local tackle shop.

Barker wrote that it was unfortunate that Walleye Jackpot organizers had canceled their event, and while he acknowledged that without a Pikeminnow Program-like reward on their heads it was unlikely anglers themselves would ever knock down the walleye population, he still felt a civic calling straight out of the LC Valley.

“The idea that the more of them I eat, the more I’m helping native salmonids is pleasing to me,” he wrote.

Having chronicled the entry of another toothsome predator into this same countryside, Barker also modified some bumper-sticker slogans for the cause: “Save a Salmon, Wack a Walleye”; “Walleye: Smoke a Stringer a Day”; “Walleye CCC: Cast, Cook and Consume.”

The rise of walleye numbers at both Lower Granite’s Boyer Park and the Snake-Clearwater confluence was predicted as far back in 2017 by a purported top 20 pikeminnow program angler based on rising catches and reports they saw, but it’s taken off far faster than even they imagined.

When 2022’s reward fishery wrapped up, I emailed WDFW’s Donley about the increasing numbers of walleye being turned in by participants at Lower Granite Dam even though no money is offered for them. I asked whether those pikeminnow anglers might be first and foremost salmon and steelhead fishermen concerned about walleye predation, and so they were doing something about it.

“I’d like to think that our consistent message that walleye are bad for salmon and steelhead would get people on board with killing them,” Donley replied. “However, after 27 years I’ve learned that many anglers don’t believe us and some simply won’t agree out of politics of identity or spite. Who knows, maybe pikeminnow anglers are more enlightened about salmon and steelhead conservation. We’ve been consistent in our message, so maybe someone is listening.”

THIS IS ANOTHER ONE OF THOSE issues that tears me up. Just as with tribal netting of spinyrays that began on Lake Sammamish a few years ago to clear the way for outmigrating Chinook and coho fry from Issaquah Creek Hatchery, I can see both sides on the Snake.

As a native Northwest salmon and steelhead angler, I’ve banged the drums about controlling piscivorous fish, birds and marine mammals, I’m invested in continued hatchery production for river and ocean fisheries and conservation purposes, I advocate for restoring habitat for the extended instream rearing of wild fish, so it’s hard not to see this walleye invasion into perhaps the last best coolwater spawning and rearing grounds in the watershed as anything but an existential threat that must be met head on.

Yet as a regional hook-and-bullet magazine editor, it’s hard to ignore the rise of a still relatively new fishery, one that’s created its own tackle lines, one that attracts anglers from as far away as the Midwest, one that I’ve put on my cover many, many times, and more than likely will again, so it’s hard not to be a bit protective of that too.

I know I don’t have answers, but I do know that there are hundreds upon hundreds of river and reservoir miles in the Columbia Basin where walleye can already be targeted and never ever will be eradicated, even if Glacial Lake Missoula blows out again, the radioactive Hanford Plume reaches the mainstem, the Chief Joseph Dike Swarm fires up and bleeds basalt all the hell over the place.

I wonder if, given the still relatively early colonization of walleye above Lower Granite, the new all-of-government approach to salmon restoration and the importance of this region for native fish – as well as their unparalleled cultural weight – an argument might be made to designate this part of Washington’s, Oregon’s and Idaho’s Snake River as a walleye control zone, à la sea lions at Bonneville and Willamette Falls during salmon runs, cormorants on Oregon Coast bays during smolt outmigration, smallmouth on the Coquille – a place where they are just not tolerated.

Admittedly, it’s all kind of a have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too approach, but it seems more viable than doing nothing about a growing problem or trying to go nuclear on it.

But what do I know? The real ideas are going to come out of that state-tribal-federal Walleye/Non-Native Piscivore Work Group that I mentioned in the first few paragraphs of this story.

As word gets out about it, there’s the potential for a firestorm, so I think the first thing they need to do is create a website that better lays out who they are, the area they’re looking at, the scope of their aims and mission statement, the authority they wield to put those into motion or how they would, etc.

And I think they should also consider bringing anglers onboard the panel – salmon, steelhead, bass, walleye, channel catfish fishermen, guides, tournament directors, pikeminnow program participants. Representatives could serve as sounding boards, provide feedback and serve as messengers back to organizations and forums deeply invested in the topic about the increasingly critical need to act here.

The time to do something was a few years ago now, but there’s no time like the present either.