Mule Deer Migration Impacted By Energy Development

If it’s October, I’ve got mule deer on my mind. As I prepare to head to my Northcentral Washington hunting grounds, I’m waiting to hear how my wife’s uncle did in Northcentral Oregon, a trip I was invited on.

In recent weeks, besides diving deep into WDFW’s district forecasts and bugging the agency’s wildlife biologists for my annual deer hunting prospects, I also recently wrote about how collared muleys are navigating the peril and productivity of Okanogan burn scars, which provide a lot of summer forage for the deer, fattening up bucks, does and fawns alike.

One thing that I didn’t realize until several years ago now is how the migration of pregnant mule deer does from the valley floor to their summer range is less of a head-down, let’s-get-this-over-with, straight-through march – like I guess I kinda always imagined – than a series of stutter steps across the landscape as patches green up.

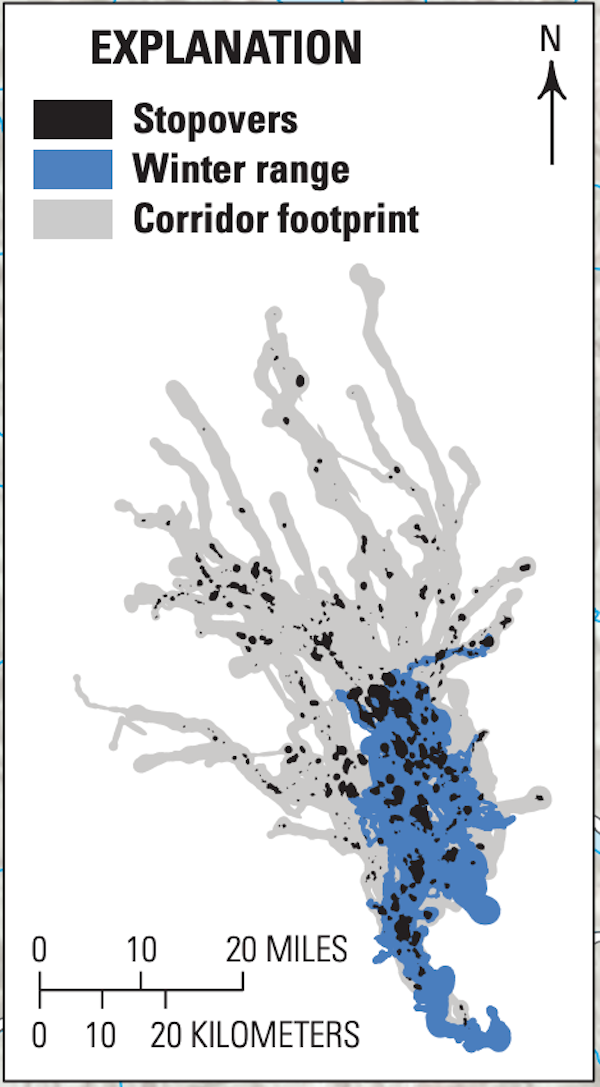

A map from the U.S. Geological Survey’s Ungulate Migrations of the Western United States, Volume 2, published earlier this year, illustrates these “stopover” points for Washington’s western Okanogan County herd.

Overall, these stopovers represent a tiny fraction of the herd’s overall 1.6-million-acre migratory corridor – just 71,634 acres – but they’re critical, critical foraging areas coming out of the lean times of winter and heading into the fawning season.

So this morning when a USGS press release on mule deer usage of stopover points during their spring/summer migration – some call it “surfing the green wave” – came across the wire, it caught my eye. It’s about how federal and university researchers found energy development in Wyoming is slowing the flow of deer across the land, making the herds more likely to miss the peak of forage at their next stopovers.

Yes, there can be no doubt that the rise of wolves alongside cougars are impacting our big game, but this study reemphasizes the importance of habitat and how alterations to it affect ungulate health.

Well-fed does beget healthier, stronger, faster fawns, making them more likely to escape predators jaws and survive the next winter to beget more healthier, stronger, faster fawns.

Sorry to (once again) get up on my Habitat! Habitat! Habitat! soapbox – and it should be pointed out that current events are clearly showing us we need to think hard and long about how we source energy in the future – but for what it’s worth, here’s that USGS press release in full for your own mulling:

Energy development in migration corridors affects mule deer access to best forage

Findings highlight the need for migration maps in future development decisions

Laramie, Wyo.—When migrating mule deer encounter energy development, they stall just long enough to let their spring forage go stale, according to a collaborative study published today led by the U.S. Geological Survey and University of Wyoming.

The study quantified how the migratory behavior of mule deer is affected by energy development, specifically coalbed-methane well construction, in their migration corridors.

“Mule deer are known for how precisely they match their movements with spring green-up, so this result was particularly striking,” said Ellen Aikens, lead author and assistant leader of the USGS South Dakota Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit. “The gas wells caused them to let the best food of the year slip away from them.”

Each spring in the American West, mule deer time their migrations to follow the greening up of plants, which sprout at different times across different elevations and latitudes, a behavior that biologists term “surfing the green wave.” This behavior helps deer to find the youngest and most nutritious plants, aiding their recovery from winter and fattening them up for breeding season and the next winter.

The 14-year-study followed a herd of migratory mule deer that winter in sagebrush basins and summer in the Sierra Madre Mountains, about 15 miles southwest of Rawlins, Wyoming. Over the study period, dozens of new wells were drilled for coalbed-methane extraction in the middle of an existing mule deer corridor. The long-term movement data allowed the team of scientists to compare mule deer migration patterns over time as development expanded.

The team analyzed deer movements alongside daily changes in spring green-up, estimated using remote satellite imagery, to measure how well deer surfed along the corridor over the 14-year period.

“The deer movements in response to the developments found in the gas field were unmistakable,” Aikens said.

As development intensity increased over time, the deer began to “hold up” when they reached the natural-gas wells. They paused their spring migration and let the wave of green vegetation pass them by, becoming decoupled from their best food resources at a crucial time of the year.

Overall, the wells resulted in a 38.65 percent reduction in green-wave-surfing through time. There was no evidence that mule deer acclimatized to the development or the related increases in human presence, truck traffic and noise. Small- and large-scale developments altered green-wave-surfing behavior to a similar degree.

The study will help wildlife managers understand how development reduces the ecological functionality of migration corridors. In this case, deer were still able to move through the gas field despite the development, but a key function of the migration corridor—to gain maximum nutrition all along the route at the ideal stage of plant growth—was lost. Without this well-timed access to the green wave, deer can’t realize the full benefit of migration.

“This study makes clear that when development continues to erode the value of corridors, it could have long-term effects on these migrations. But it points to conservation solutions as well,” said co-author Matt Kauffman of the USGS Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit at the University of Wyoming. “Once migration corridors have been mapped, development can be planned to minimize disruptions to migrating herds whether in Wyoming, the American West, or wherever landscapes are rapidly changing.”

Numerous state and federal initiatives in the U.S. have been launched in the last five years to map migration corridors with the goal of reducing impacts to them. In Wyoming, for example, state wildlife managers have long sought to map and conserve migration corridors, a practice now guided by state policy.

“This new research provides the most convincing case so far that efforts to minimize development within migration corridors will benefit their long-term persistence amid changing landscapes,” Kauffman said.

The paper “Industrial energy development decouples ungulate migration from the green wave” was recently published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution. Additional co-authors included Teal Wyckoff of The Nature Conservancy and Hall Sawyer of Western EcoSystems Technology, Inc.