Governor Jay Inslee is butting into Washington predator management yet again, yet again around wolf-livestock conflict management, and it may do nothing but further chill the atmosphere around an already-polarizing species otherwise doing just fine in the state.

He ordered WDFW today to begin “new rulemaking” to consider adopting the agency’s advisory group’s lethal removal protocols “as regulation or policy,” a far more shackling approach than the one that has been favored by state wolf managers and a tack that was rejected in late October by the Fish and Wildlife Commission on a 6-3 vote.

Inslee also wants WDFW to consider “new policies or regulations” around what’s known as “caught in the act” rules that allow ranchers, their hands or everyday residents to shoot a wolf seen attacking their stock or domestic pets in the federally delisted eastern third of the state, but which the state’s chief executive worries “may be used to unjustly kill an increasing number of Washington’s wolves.”

The Center for Biological Diversity termed the governor’s order “a win for wolves” and hoped “the third time’s the charm” in their bid to butt into Washington wolf-livestock conflict management.

“And I hope that this time the state will listen to the science and adopt rules that will reduce wolf killing and lessen livestock losses,” said CBD’s Amaroq Weiss in a press release. “Commonsense measures like the ones we proposed will set Washington on track to truly coexist with wolves.”

Washington already coexists well with wolves. A 2022 review by Conservation Northwest termed the state “the best place to live if you are a wolf in the western United States” because of Washington’s lowest rate of human-caused wolf mortality.

Wolves in federally delisted Northeast Washington, where most livestock conflicts and caught-in-the-act shootings have occurred, are essentially at carrying capacity and have sustained their numbers in the face of occasional WDFW lethal removals and years of legal hunting by two different tribes, all while contributing to populations elsewhere in the state and region via dispersals.

“I’m disappointed in Governor Inslee’s action today, caving-in to pressure that could re-polarize Washington’s successful wolf recovery,” stated Mitch Friedman, Conservation Northwest’s executive director. “Washington has the nation’s most successful wolf program, with much higher stakeholder effort leading to much lower wolf conflict and mortality. For instance, even Oregon killed over eight times more wolves than Washington last year. When something as volatile as wolf recovery is going well, you stick with it. I fear wolves will pay the price for today’s overreach.”

Scott Nielsen, who represents ranching interests with Cattle Producers of Washington, said Inslee’s directive was about “a problem that doesn’t exist” and forecast that it wouldn’t “really be well received by the ranchers,” according to an article out late in the day from the Capital Press.

Today’s directive from Inslee follows a petition filed last November by Arizona-based CBD and 11 other out-of-state and in-state organizations after the commission said nope to their petition for WDFW to initiate rulemaking.

In a letter to the governor at the time, the groups said they want “enforceable” standards around lethal removals, which Weiss described in a supporting letter as “requirements that must be met before the state will consider killing wolves.”

WDFW had argued last fall against codifying wolf management rules because it felt conflict prevention is better handled by local staff building personal relationships with livestock operators, continuing with the years-long collaborative process seen with the Wolf Advisory Group and the hard-won agreed-to protocol, and expanding proactive nonlethal deterrences and figuring out new programs along those lines.

This is not the first time Inslee has dipped into WDFW wolf management (or predators, for that matter). In September 2020 and chivvied by some of the same cast, he ordered WDFW to begin rulemaking around wolf-livestock conflict management, but after a long internal process, the commission ultimately demurred in a very testy 5-4 May 2022 vote, with Chair Barbara Baker stating that approving the new rules would “chill the advancements we are making.”

With a hard freeze having now descended on the state and in response to Inslee’s directive, WDFW outlined similar bids filed over the years and noted that following a 2019 letter from the governor the Wolf Advistory Group adopted a protocol with the aim of reducing wolf removals.

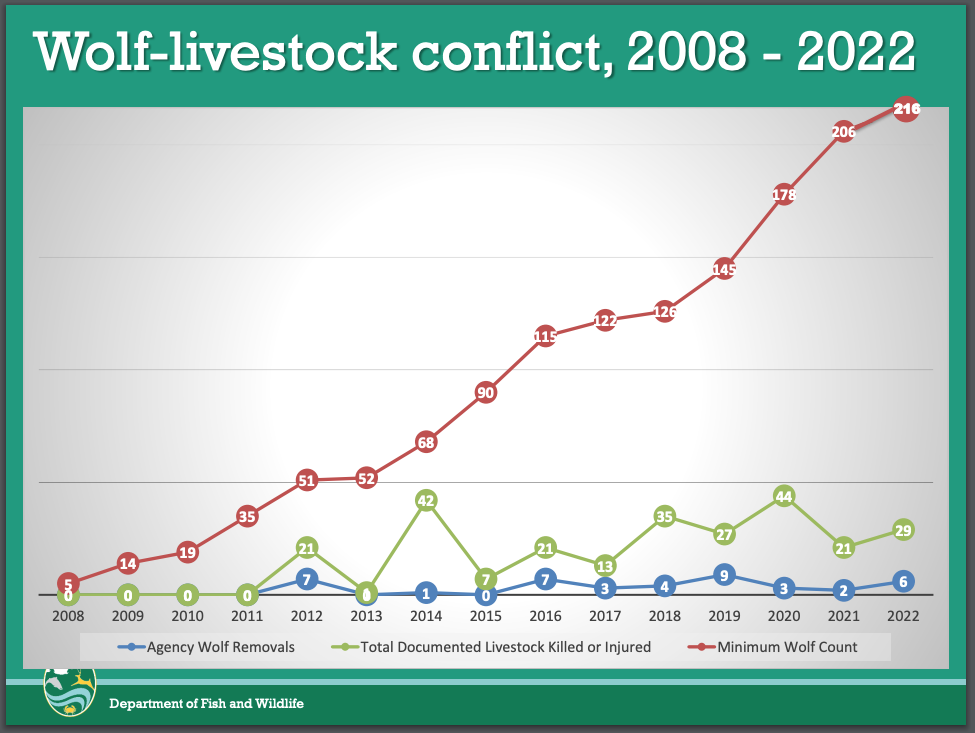

“WDFW has significantly reduced the need for lethal removal of wolves. In 2019, WDFW lethally removed nine wolves. This was followed by three in 2020, two in 2021, six in 2022, and two in 2023 – a 64% average reduction over the four years following 2019,” an agency statement out this afternoon said.

“In the meantime, the number of wolf packs, successful breeding pairs, and individual wolves in Washington has continued to increase every year, while levels of livestock depredation and wolf removals have remained low even with wolf range expansion and population increase,” it continued.

Nevertheless, WDFW said it would “review and comply with the directive and staff will meet with the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission regarding the timing and process for initiating rule making.”

Inslee noted that while he “cannot legally prescribe the specific policies that must be included in new rulemaking,” he recommended WDFW consider:

• Adopt the Wolf Advisory Group’s lethal removal protocol as regulation or policy. I appreciate that the Director has utilized the protocol in his decision-making regarding lethal removal. Putting the protocol into rule or policy would provide consistency, continuity, and confidence for future administrations.

• Consider new policies or regulations on “caught in the act” procedures, as a number of wolves have recently been killed under “caught in the act” when they were not attacking livestock. If not restricted and carefully monitored, this vague policy may be used to unjustly kill an increasing number of Washington’s wolves.

The caught-in-the-act rule was passed by the Fish and Wildlife Commission in the early 2010s at the behest of a bipartisan group of state lawmakers. It’s only valid in the federally delisted portion of the state and has been used nine times, or just under once a year on average.

The governor said he appreciated the work WDFW, the commission and Wolf Advisory Group had done in terms of working with stakeholders on “long-term solutions” around wolves and conflict, and in today’s letter he thanked Claire Loebs Davis of Washington Wildlife First for her “work to preserve the health of Washington’s endangered wolf population.”

WDFW is proposing to actually downlist it to protected-sensitive status, which Inslee opposes as well.