After More Than A Decade, Wolves Leave WA’s Teanaway

Wolves have abandoned – perhaps only temporarily – one of the oldest pack territories in Washington after its lone male left the Teanaway last month, ending one of the most unusual chapters in Evergreen State wolf lore.

WDFW reports the wolf, which was captured and GPS-collared in 2020 and is known as 106M, headed south across I-90 and is being monitored remotely by state biologists.

“He had been hanging around by himself all last summer, fall and winter and (WDFW wolf biologist) Ben (Maletzke) thinks he decided to strike out to find greener pastures somewhere else,” stated agency spokeswoman Staci Lehman in Spokane. “Perhaps find another wolf.”

The black-coated male, estimated to now be around 6 years old, won’t find many in the direction it’s apparently headed, but last spring the Big Muddy Pack did form in Washington’s South Cascades, a first for WDFW’s South Cascades and Northwest Coast Recovery Zone, and it’s likely they have a litter this year. There could be fellow dispersers there, of course, and further south are Oregon wolves.

It’s unclear where 106M came from – DNA samples were taken but results haven’t come back, per Lehman – but it settled in with the Teanaway Pack sometime during the winter of 2019-20, perhaps leading its aging breeding male to depart.

Wolves have been in this part of Kittitas County likely since at least 2010, with a pack confirmed by WDFW in 2011. Washington’s fourth known pack, Teanaway was linked to its first, the Lookout wolves of Okanogan County, and that’s where this particularly odd chapter begins.

The original breeding pair, 32M and 012F, were siblings born in the Methow Valley above Carlton and Twisp and later headed south down the east slopes of the Cascades. Settling in the Teanaway they had a litter and after 012F disappeared, 32M bred two of their offspring, 038F and 072F.

At the time, the pack was Washington’s “most geographically isolated,” raising the likelihood of inbreeding, which occurs when wolves are cut off from other source populations such as at Isle Royale on Lake Superior and Scandinavia west of reindeer herding areas, or dispersers on their firespark-like walkabouts don’t connect with other wolves.

WDFW’s record keeping has changed over the years, but based on tallies in the agency’s annual reports, 32M could have sired around 20 pups that lived to see their first year, and perhaps as many as 40, given 50 percent mortality rates for young-of-the-year wolves.

Thirty-two-M’s breeding days came to an end in the winter of 2019-20, perhaps with the arrival of 106M or maybe just old age. It headed a bit to the east, was involved in the probable depredation of two calves, and died of natural causes in July 2020 at 12 years of age, then became the subject of a WDFW tribute video.

Its incestuousness was not mentioned in the video, nor the Pacific Wolf Family’s profile of the pack.

WDFW’s subsequent year-end counts show five Teanaway wolves at the end of 2020 – 106M and four others – four when 2021 wrapped up and just 106M as 2022 came to a close.

Why the pack petered out, especially with new blood, is anyone’s guess. I’m no wolf biologist, of course, but it probably won’t be too long before another sets up shop here, especially given the creep of other wolf groups down the east slopes of the Cascades the past few years.

Wolves’ long existence in the Teanaway points to a landscape conducive to Canis lupus; it’s home to big game like mule deer and elk, as well as rabbits, birds and other critters these generalists consume. While the territory is penned in by I-90 and Highway 97 on the south and east, it also backs into wilderness with summer and winter ranges for several migratory herds.

(As a deer hunter, I decided to compare Teanaway Game Management Unit general season rifle buck harvest and days per kill with known Teanaway Pack year-end wolf numbers since 2013 – the range of immediately available WDFW deer harvest data – and it produces some very interesting vacillations, but nothing that this non-stats major can categorically declare a clear correlation between pack size and hunter take, plus harvest is strongly affected by fawn recruitment a year or more beforehand, which itself is impacted by doe productivity, summer forage and winter severity; the deer population and its relative availability in fall, i.e., state of the migration, if applicable; weather conditions during the season; season dates; hunter pressure and … well, let’s move on with this, it’s hurting my head.)

And there are fewer grazing allotments in the overall neighborhood than Northeast Washington. The Teanaway wolves had relatively few depredations, at least compared to Wedge and other Washington problem packs, which might have been due heavy range-riding and other nonlethal conflict prevention measures. This part of the state falls under the reinstated federal listing, but is there any guarantee that the next pack will be so well-behaved?

In fact, the area might not go long without a pack, as a wolf or two may be sniffing around already.

WDFW’s Monthly Wolf Report for March states, “At least one wolf has been captured on cameras southwest of the Teanaway pack territory but north of Interstate 90 this past month. Also, at least one wolf has been located in the adjacent and vacant Naneum territory.”

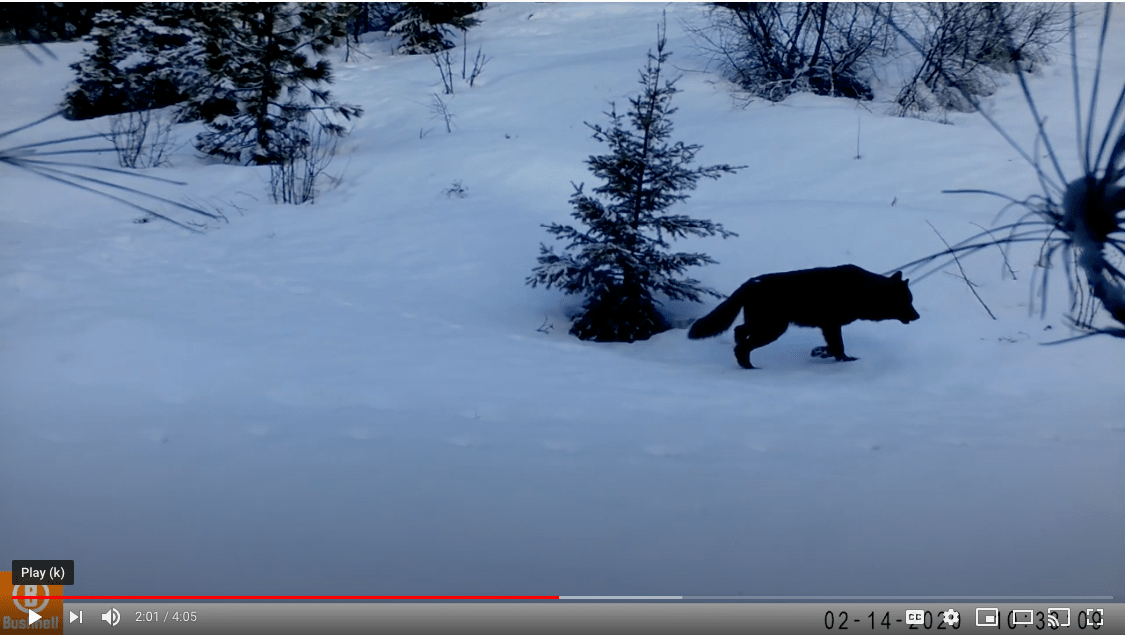

One of the two would seem to correspond to a vaguely worded WDFW Wildlife Program report for late March – “District 8 Assistant District Biologist Wampole and Conflict Specialist Wetzel confirmed wolf presence of an uncollared individual in the district. District biologists will continue to monitor the area for wolf activity” – which also includes a pic of tracks in snow and this trail cam image:

Wolves are a royal pain in the ass – or at least the wolf people on the fawning and foaming fringes are – but all the information collected from collaring and monitoring those in Washington makes for unexpected insights as with the Teanaways, as well as how many have ended up brain-bitten by cougars relative to elsewhere in the Northern Rockies.